- More than four in 10 Kenyans say they felt unsafe while walking in their neighbourhood (45%) and feared crime in their home (42%) at least once during the previous year, including about one in four who experienced this at least "several times." Poor citizens are far more likely to be affected by such insecurity than their better-off counterparts.

- About half (48%) of Kenyans live within easy walking distance of a police station.

- About one in five citizens (19%) say they requested police assistance during the previous year. More than twice as many (44%) encountered the police in other situations, such as at checkpoints, during identity checks or traffic stops, or during an investigation.

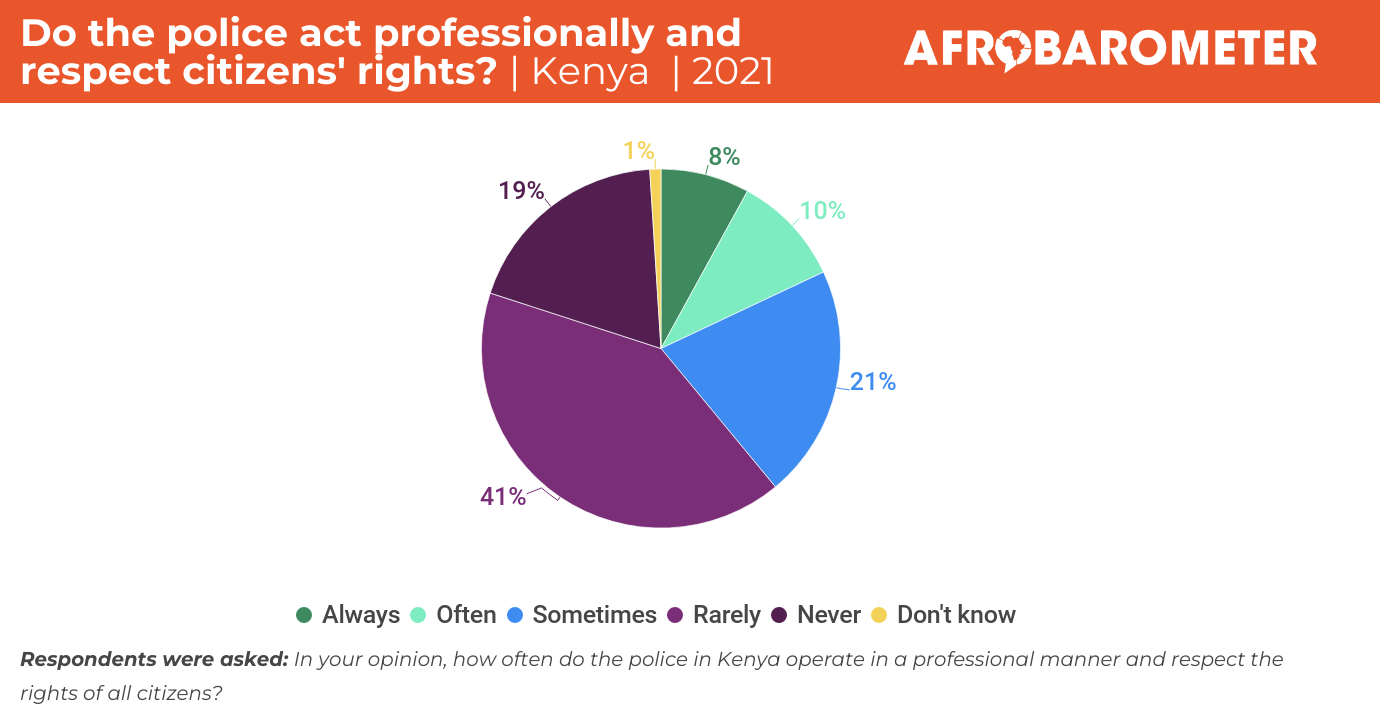

- More than two-thirds (68%) of citizens say that "most" or "all" police are corrupt – by far the worst rating among 12 institutions and leaders the survey asked about.

- Only about one in three Kenyans say they trust the police "somewhat" (21%) or "a lot" (13%). The share of citizens who say they don't trust the police "at all" has climbed by 12 percentage points since 2014.

The police are the most visible representatives of the government. In the hour of need or danger, when a citizen does not know what to do or whom to approach, a police station and a police officer are the most appropriate and approachable entities. The police are expected to be the most accessible, interactive, and dynamic organisation in society. They are also expected to uphold the highest standards of professionalism, whether dealing with citizens at their most vulnerable or at their worst.

Critics have long accused Kenya’s police of falling well short of these expectations, alleging police abuses ranging from brutal treatment of suspects and protesters to corruption, robbery, and extrajudicial killings, often with impunity (Capital News, 2022; VoA, 2020; Hope, 2015; Onyango, 2022).

While frequent calls for reform have led to some changes, including provisions in the 2010 Constitution for a unified National Police Service and an inspector general, they have more often been stymied by political elites interfering with police operations as an independent body (Mageka, 2015).

This dispatch reports on a special survey module included in the Afrobarometer Round 9 (2021/2022) questionnaire to explore Africans’ experiences and assessments of police professionalism.

In Kenya, fully half of adults report encounters with the police during the year preceding the survey, either to request assistance or, more often, in situations such as checkpoints or traffic stops. Many of these encounters involve the payment of bribes, and the police are more widely seen as corrupt than any other institution the survey asked about. Only one-third of Kenyans say they trust the police.

Instead, most say the police engage in illegal activities, fail to respect citizens’ rights, stop drivers without good reason, and use excessive force in managing public demonstrations and dealing with criminals. Fewer than half of Kenyans say the government is doing a good job of reducing crime.

Related content