- Across 31 countries, traditional leaders consistently receive significantly more positive ratings – on trust, performance, listening, and lack of corruption – than their elected counterparts (presidents, members of Parliament, and local government councillors).

- While high trust extends across many countries, there are outliers. Fewer than four in 10 citizens express significant trust in traditional leaders in Tanzania, Sudan, Morocco, and South Africa.

- Trust in traditional leaders is much higher among rural respondents, increases with respondents’ age, and decreases with education, but pluralities express trust across all key demographic groups.

- Men and women express nearly equal levels of trust, despite the patriarchal nature of most traditional leadership institutions.

- Across 17 countries tracked since 2008/2009, trust in traditional leaders has held steady while trust in elected leaders has dropped substantially, leading to a widening trust gap between chiefs and other leaders.

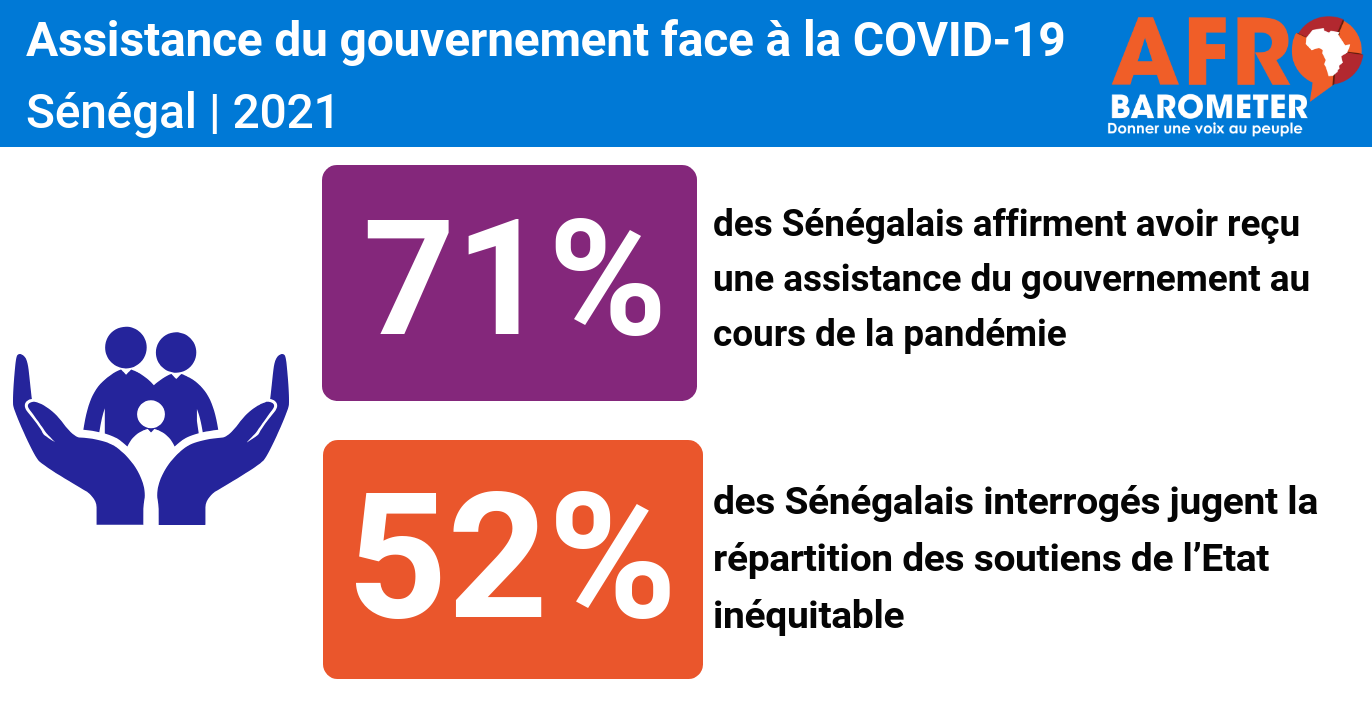

The proper role for unelected “traditional leaders” or “chiefs” in modern African societies has been debated for decades. Once written off as anachronistic, irrelevant, and anti-democratic, especially after the democratic openings that swept across the continent in the 1990s, chiefs have been resurgent in recent years, establishing themselves as an integral part of the fabric of local governance in many countries. The unelected chieftaincy has not just coexisted but thrived alongside the practice of democracy, elections, and multiparty competition. In many places chiefs work in tandem with local councillors to allocate land, resolve conflicts, and govern communities. Most recently, chiefs have been called on to reinforce national battles against the COVID-19 pandemic (Sanny & Asiamah, 2020).

New survey findings from Afrobarometer confirm that the position of traditional authorities is still strong, or even strengthening. Chiefs get consistently higher citizen ratings for trust and performance, and are seen as markedly less corrupt, when compared to elected leaders and government officials, and the gaps are widening. Chiefs find support not only among elderly rural men, but also among women, urban residents, youth, and the most educated.

They wield significant influence in their communities, especially when it comes to governance, conflict resolution, and land allocation. Moreover, people generally think they have the interests of their communities at heart and are effective in cooperating with local councillors to promote local development. In fact, by a 5-to-1 margin, Africans would prefer to see their influence increase.

Africans want their chiefs to work with elected leaders to bring development to their communities, and they even believe that the engagement of traditional leaders helps to strengthen rather than to weaken democracy.

But one area where chiefs’ influence is not welcome is electoral politics. Although much has been made of the potential role of chiefs as “vote brokers” who deliver the votes of their community members to whichever political candidate or party wins their favour (Holzinger, Kern, & Kromrey, 2016), only one in five Africans say chiefs have a lot of influence on people’s votes. And they have a clear message for their chiefs: Stay out of politics.

Related content