- Like their elders, about six in 10 young Africans (61% of those aged 18-35) say their country is going “in the wrong direction.

- Unemployment tops the list of the most important problems that young Africans want their government to address, followed by health, education, and infrastructure. Young people are more likely than their elders to prioritize government action on unemployment and education.

- Young Africans are, on average, more educated than their elders. A majority (62%) of 18- to 35-year-olds have at least some secondary school, compared to 46% and 31%, respectively, of the middle and senior age brackets. While almost all youth in Mauritius, Gabon, Zimbabwe, South Africa, and Tunisia have been to school, a majority in Niger (60%) and almost half of young Burkinabè (46%), Malians (45%), and Guineans (44%) have no formal education.

- African youth are also considerably more likely than their elders to be out of work and looking for a job (34% of youth vs. 22% of 36- to 55-year-olds and 12% of those above age 55). Unemployment rates reported by young respondents range up to 56% in Lesotho and 53% in Liberia.

- Only a minority of Africans say their government is doing a good job of meeting the needs of youth (28%), creating jobs (21%), and addressing educational needs (46%). Young and older respondents offer almost identical assessments of the government’s performance.

Addressing the needs of youth – for education, engagement, and livelihoods – has become a central tenet of global and continental policy discussions over the past decade. The African Youth Charter underscores the rights of youth to participate in political and decision-making processes and calls upon states to prepare them with the necessary skills to do so

(African Union, 2006). The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) consider youth essential partners for achieving inclusive and peaceful societies (United Nations, 2018). More than one-third of the 169 SDG targets reference youth (UNDP, 2017).

Almost 60% of Africa’s population is under the age of 25, representing enormous opportunities and challenges (Mo Ibrahim Foundation, 2019). The fact that only 14% of lawmakers on the continent are under the age of 40 highlights the gap between youth’s voice and the

importance of youth to economic and social progress (Brookings, 2019). Youth unemployment rates are double those of adults in most African countries, and 60% of Africa’s unemployed are young people (African Capacity Building Foundation, 2017). Almost half of young Africans have considered emigrating – most often in search of jobs (Sanny, Logan, & Gyimah-Boadi, 2019).

Findings from the latest Afrobarometer surveys in 34 countries shed light on challenges confronting Africa’s youth. Young citizens do not feel they are getting the support they need from their governments – and their elders agree. Younger Africans have made substantial gains in terms of educational achievement, but they still face huge gaps in paid employment, making job creation the most critical issue on the youth agenda. While both youth and older citizens support more aggressive government efforts to help young people, they give their governments failing marks in meeting these needs.

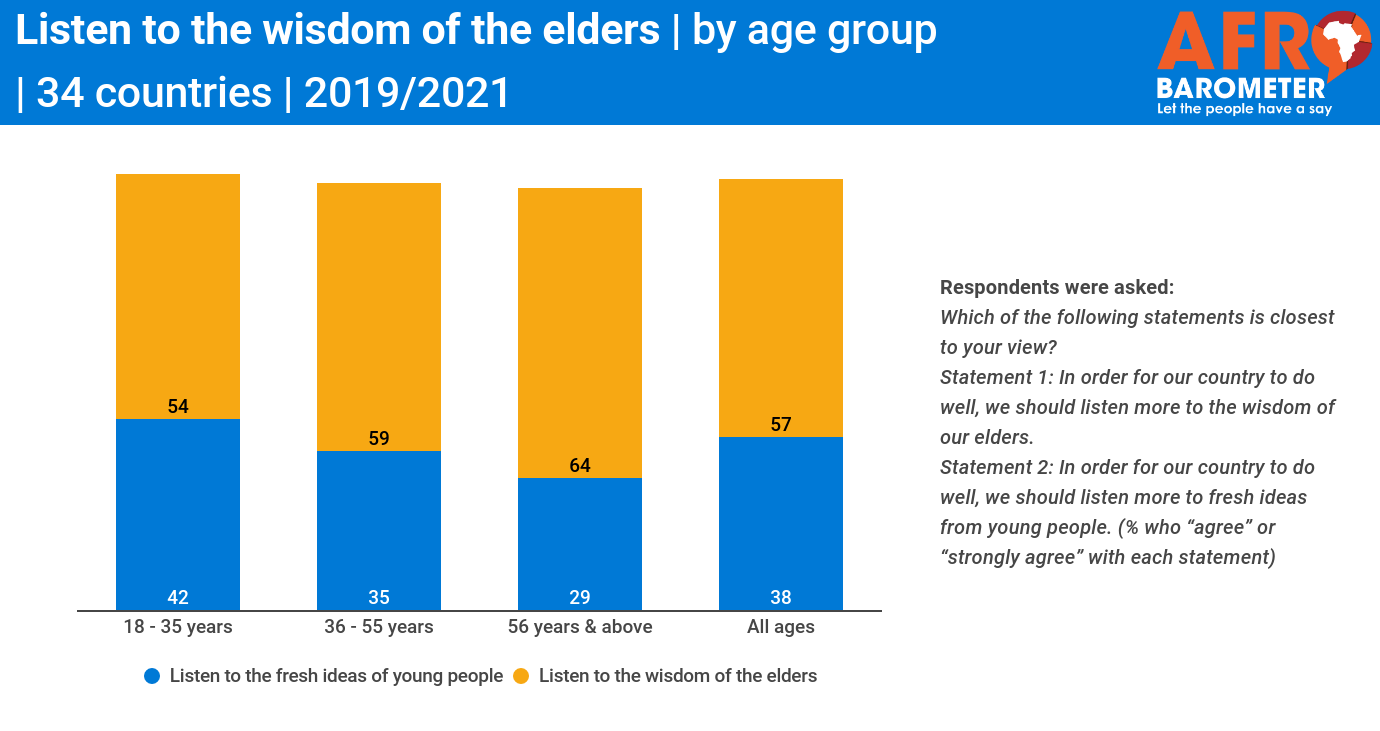

Africans of all ages seem to understand that if the youth are suffering and unable to establish productive livelihoods, this is not just a “youth problem,” but a “society problem.” But even if their elders support a pro-youth agenda, young Africans could do more to make their own voices heard directly in policy-making processes (Kuwonu, 2017; Resnick & Casale, 2011). The youth of Africa are far less likely to vote than their older compatriots, and they are generally less engaged in day-to-day political processes as well. African states have failed to effectively engage youth in governance and decision-making processes (African Union, 2017), but youth themselves could find ways – including voting – to ensure their voices are heard in the design of policies and programs to overcome the hurdles they face.

Related content