- Daily news consumption via social media (11%) and the Internet (9%) has doubled in Uganda since 2015, though these platforms still lag far behind television (27%) and radio (54%) as daily news sources.

- Six in 10 Ugandans (60%) say they are aware of social media. o Awareness is less widespread among women, rural residents, and older and less educated citizens.

- Among Ugandans who have heard of social media, large majorities say it makes people more aware of current happenings (89%) and helps people impact political processes (74%). o On the other hand, majorities also say it makes people more likely to believe false news (70%) and more intolerant of others with different political opinions (58%).

- Overall, 58% of citizens who are aware of social media rate its effects on society as positive, while only 13% see them as negative.

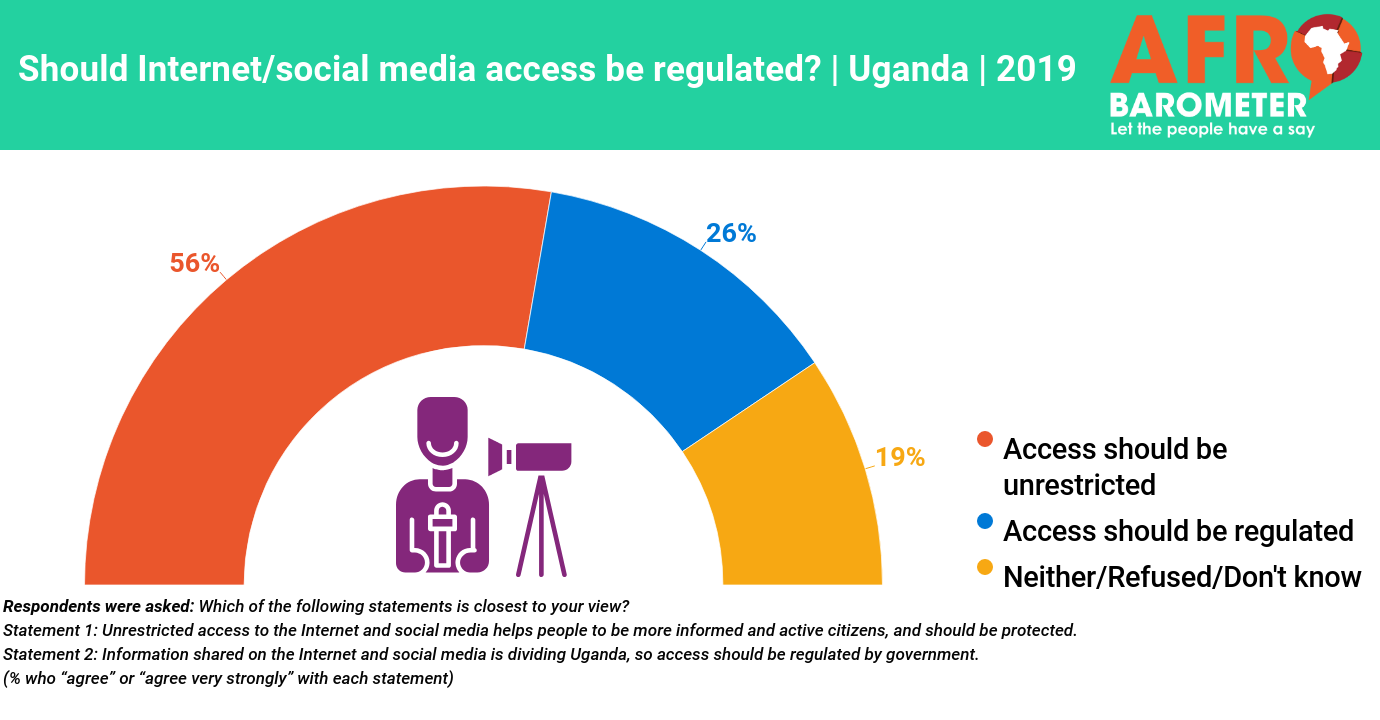

- A majority (56%) of Ugandans “agree” or “strongly agree” that access to the Internet and social media helps people to be more informed and active citizens, and should be unrestricted. A quarter (26%), however, say the government should be able to regulate access.

In Uganda, restrictions on Internet and social media use are becoming common. Since 1 July 2021, Internet users have begun paying a 12% tax on Internet data, in addition to an 18% valued added tax (Mwesigwa, 2021). The Internet tax replaces the over-the-top tax, popularly known as the “social media tax,” which the government imposed in 2018 in a bid to restrict access to Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, and other platforms.

Although the government presents the new tax as an opportunity to raise more revenue, critics see it as an attack on freedom of speech and an ill-considered move during a pandemic when many services can only be accessed online (Economic Times, 2021).

Taxes are not the government’s only way of restricting Internet usage. On the eve of Uganda’s 2021 presidential election, the government imposed an Internet blackout (DW, 2021; Netblocks, 2021). A similar Internet blackout was imposed on the day of the 2016 presidential election, a move that President Yoweri Museveni defended as a “security measure to avert lies” (BBC, 2016; CNN, 2016).

Activists, opposition leaders, and several human-rights groups describe such government crackdowns on Internet and social media use as an attempt to restrict freedom of expression and suppress dissent (Access Now, 2021; Amnesty International, 2021; Anguyo, 2021).

These recurring Internet and social media shutdowns also hurt businesses in the formal and informal sector, education, health care, the media, civil society groups, and many others increasingly dependent on digital platforms (Daily Monitor, 2021a). The five-day shutdown during the 2021 election, for instance, is estimated to have cost the country about USD 9 billion (Bhalla & McCool, 2021).

Another threat to Uganda’s digital landscape comes from within: the proliferation of fake news. Despite government vows to prosecute anyone who spreads falsehoods on social media, false information continues to circulate on digital platforms. Misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines is widespread, and social media users have even announced – falsely – Museveni’s death (Xinhuanet, 2020; East African, 2021).

Findings from the Round 8 Afrobarometer survey show that a majority of Ugandans want unrestricted access to the Internet and social media, and see the overall effect of social media usage as more positive than negative. However, most are concerned about the use of social media to spread falsehoods.

Related content