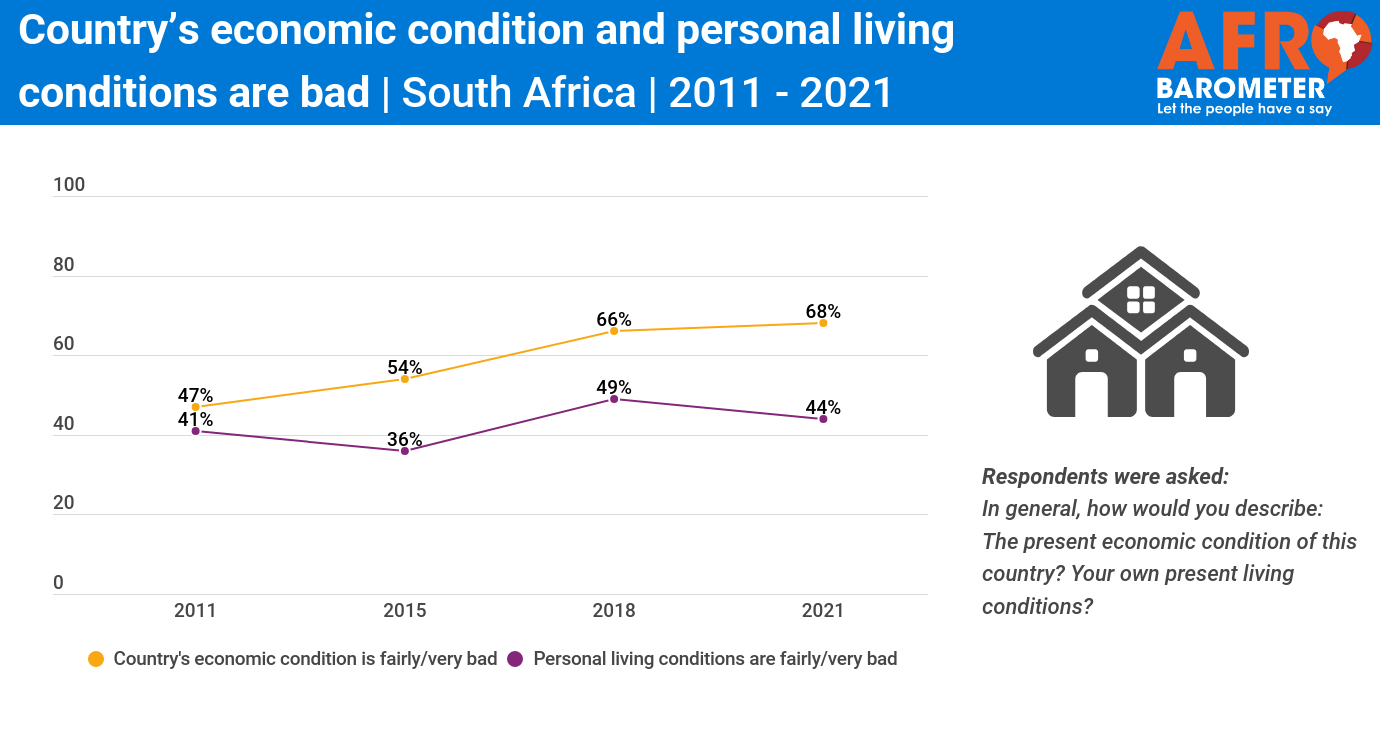

- More than two-thirds (68%) of South Africans describe the economic condition of the country as “fairly bad” or “very bad,” a 21-percentage-point increase over the past decade.

- Four out of five South Africans say the government is performing poorly on income inequality (81%) and price stability (79%).

- More than four in 10 respondents (44%) assess their personal living conditions as bad, a 5-percentage-point improvement compared to 2018, while about the same proportion (43%) describe them as good.

- Almost half (46%) of South Africans say that they or someone in their family went without a cash income “several times,” “many times,” or “always” during the previous year. About one-third of citizens report having repeatedly gone without enough clean water (34%), enough cooking fuel (33%), or enough food (32%).

- Two-thirds (66%) of citizens say people are at least “sometimes” treated unfairly by the government based on their economic status.

In South Africa, the economic hub of Africa, years of stifled growth have been worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic’s extended restriction of economic activity. The economy shrank by 7% in 2020 (World Bank, 2020), causing widespread material deprivation, job losses, and anxiety about the future. Signs of recovery, though seen for four consecutive quarters, have been modest (Statistics South Africa, 2021a).

The country’s economy is characterized by high levels of poverty, unemployment, and inequality (Department of Trade and Industry, 2018; Alvaredo, Chancel, Pikkety, Saez, & Zucman, 2018). The government has laid out a far-reaching Economic Reconstruction and Recovery Plan intended to address these problems by stimulating growth across different sectors (Government of South Africa, 2020). It also announced a R500 billion COVID-19 recovery package, though by February 2021 only one-third of its budget had been spent, mostly on wage relief and social security (Institute for Economic Justice, 2021).

Despite these efforts, economic agency – people’s ability to participate in and shape the economy – continues to shrink. Disrupted supply chains and inflation, which climbed to an annual rate of 5.2% in May (Statistics South Africa, 2021b), have pushed up the prices of food (Fokazi, 2021), water, electricity, and sewer services.

These constraints on prosperity have the potential to erode social cohesion and stability (Patel, 2021), as we saw in July 2021 when parts of the country were plunged into rioting and looting of goods ranging from basic necessities to luxury items (BBC, 2021). Although underpinned by factional wars within the ruling party, these events spiraled out of control because of desperation among the population. The impact of the looting continues to affect a wide range of South Africans, from business owners to employees and even locals in affected areas who now must travel farther to access goods and services (Makhaye, 2021).

The most recent Afrobarometer survey findings offer a fairly grim view of South Africa’s economic situation. A majority of citizens see economic conditions as worse than a year ago, and fewer than half expect things to get better over the coming months. Large proportions of the population experienced shortages of food, clean water, medical care, and a cash income. And a majority say the government is not only doing a poor job of reducing income inequality and keeping prices stable, but also treats people unfairly based on their economic status.