- ▪ By a 2-to-1 margin (61% vs. 32%), Africans say their governments have the right to make people pay taxes. But perceptions of taxation as legitimate are relatively low in Angola (36%), Malawi (37%), and Lesotho (40%), and are also lower among poorer, less educated, and unemployed citizens.

- Africans tend to think that ordinary people pay too much in taxes and rich people pay too little. Most Africans (70%) endorse the principle of taxing the rich at higher rates to support programs that help the poor. Views are divided on whether the government should make sure that small traders and others in the informal sector pay taxes.

- Only half (49%) of Africans believe that their governments use tax revenues for the well-being of their citizens. Two-thirds (67%) want Parliament to monitor how tax revenues are spent.

- In most countries, citizens are sharply divided on whether they would be willing to pay higher taxes in exchange for better government services.

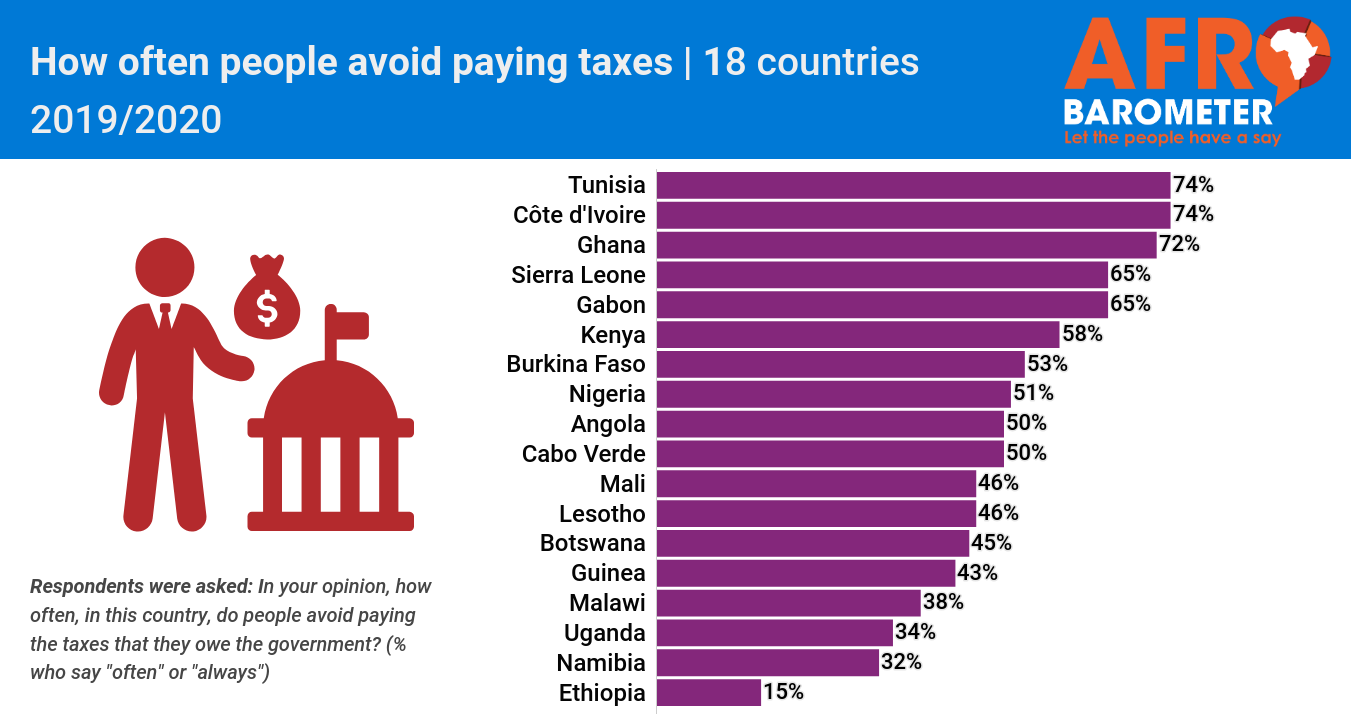

- Fully half (51%) of Africans say that people in their country “often” or “always” avoid paying taxes they owe. Large majorities say tax avoidance is common in Côte d’Ivoire (74%), Tunisia (74%), Ghana (72%), Gabon (65%), and Sierra Leone (65%).

- More than six in 10 respondents (62%) say it is difficult to find out what taxes or fees they are supposed to pay, and even more (77%) find it difficult to discover how their government uses tax revenues.

- More than one-third (35%) of Africans say that “most” or “all” tax officials are corrupt, and a further 43% see “some” as engaged in graft. Only four in 10 Africans (39%) say they trust the tax or revenue office “somewhat” or “a lot.”

- Perceptions of taxation as legitimate are stronger among citizens who trust the tax office and ruling party, and who think the government is using tax revenues to serve the public’s needs.

Taxation is a key fiscal tool for domestic resource mobilization for countries around the world. In many African countries, however, weak tax-administration systems limit the ways in which governments can finance their development agendas and provide essential services such as health care, education, and infrastructure (Drummond, Daal, Srivastava, & Oliveira, 2012).

Tax revenues are relatively low across the continent. In 2018, 30 African countries had an average ratio of taxes to gross domestic product of 16.5% – less than half the ratio in far wealthier member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (34.3%) (OECD/AUC/ATAF, 2020).

In addition to capacity limitations of government tax agencies, low tax revenues can be related to macroeconomic factors such as large agricultural and informal sectors, which are typically hard to tax (Di John, 2006; Mansour & Keen, 2009; Coulibaly & Gandhi, 2018; Moore, Prichard, & Fjeldstad, 2018). One current debate concerns how to tax highly digitalized businesses – which operate in African countries without necessarily having an easily taxable physical presence – in a way that is fair and doesn’t impede the growth of start-up companies (African Tax Administration Forum, 2020).

But low tax revenues can also reflect micro-level factors such as citizens’ willingness to pay taxes (“tax morale”), their knowledge about what they owe and what their taxes are used for, and their perceptions of corruption in the tax administration (OECD, 2019). If citizens regard paying taxes as a fiscal exchange or contractual relationship (Moore, 2004), such perceptions can affect the legitimacy of taxation as a whole (D’Arcy, 2011).

Afrobarometer survey data collected in 18 African countries in 2019/2020 show that a majority of Africans endorse their government’s right to collect taxes. But this support for taxation has weakened over the past decade while perceptions that people often avoid paying their taxes have increased sharply.

Moreover, many Africans question the fairness of their country’s tax burden, and only half think their government is using tax revenues for the well-being of its citizens.

While a majority would pay higher taxes to support young people and national development, most say they find it difficult to get information about tax requirements and uses, and many see tax officials as corrupt and untrustworthy. Such perceptions may play a role in how willingly citizens support – and comply with – their government’s tax administration.

Related content