- Seven in 10 Ghanaians (72%) want women to have the same chance as men of being elected to political office, but a quarter (24%) still think men make better leaders than women.

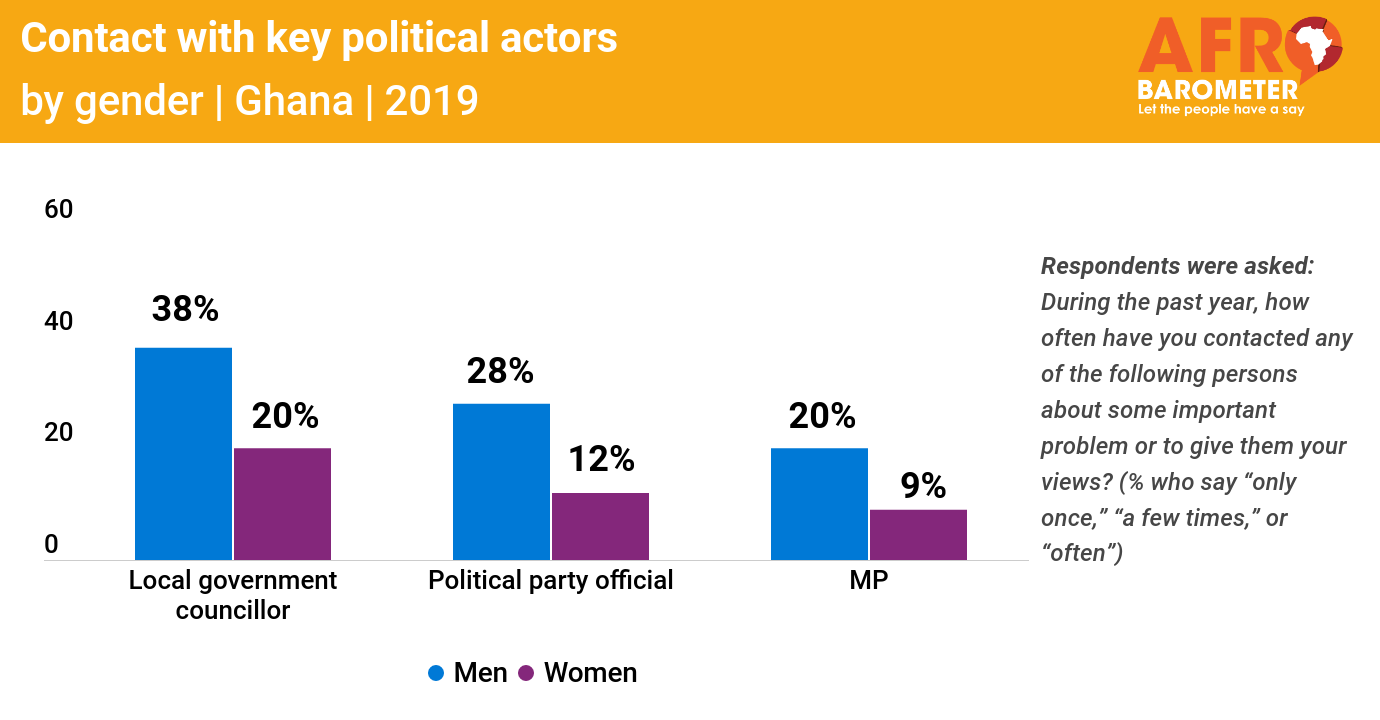

- Women and men are equally likely to say they voted in the 2016 elections, but women lag behind men in other forms of political and civic engagement. These include an 18-percentage-point gap in joining others to raise an issue (53% of men vs. 35% of women) and 11-point gaps in discussing politics (70% vs. 59%) and attending community meetings (55% vs. 44%).

- Men are twice as likely as women to have post-secondary education, whereas women are twice as likely as men to lack formal education.

- Women trail men in the ownership of a range of key assets, including a bank account (19-percentage-point difference), motor vehicle (17 points), computer (12 points), and mobile phone (9 points).

- Since 2008, women’s disadvantage in digital connection has consistently widened (from 5 to 17 percentage points) even though women’s regular use of the Internet has increased.

Over the past three decades, Ghana has taken a variety of steps to promote gender equity. Its 1992 Constitution guarantees equality and freedom from discrimination (Government of Ghana, 1992). In 1998, Ghana began working on – but has still not passed – an Affirmative Action Bill that seeks to promote a progressive increase in active participation of women in the public bureaucracy to a parity of 50% by 2030.

The National Gender Policy followed in 2015, aiming “to mainstream gender equality concerns into the national development processes” (Ministry of Gender, Children and Social Protection, 2015). The government has expressed its full commitment to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including Goal 5, which calls for ensuring women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decision- making in political, economic, and public life.

Progress has been measurable but modest. The number of female parliamentarians has grown from just one out of 140 in 1969 to 31 out of 275, or 11% (Ghana Centre for Empowering Development, 2019). In 2020, for the first time in Ghana, a major political party (the National Democratic Party) has nominated a woman as its vice presidential candidate, while a woman heads the Progressive People’s Party ticket. But these are a far cry from the kind of robust political participation and representation by women that the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) describes as “key indicators of the general level of public sector effectiveness and accountability in a country” (Asuako, 2017, p. 5) and “a key driver for advancing gender equality” more broadly (United Nations Development Programme, 2016).

Analysts point to a variety of economic and cultural reasons why progress has been slow. Madsen (2019), of the Nordic Africa Institute, for example, cites among persistent barriers the majoritarian or “first-past-the-post” nature of Ghanaian politics (as opposed to proportional representation), the high monetary cost of running for office, and a political culture in which elected women are seen as either “small girls” or “iron ladies.”

Afrobarometer’s most recent survey in Ghana shows that even though there is strong popular support for women in political leadership, political and civic participation is lower among women than among men. The survey also shows persistent gender gaps in education, digital access, and ownership of key assets.

Related content