- As of mid-2018, only a slim majority (54%) of South Africans said that democracy is preferable to any other form of government, a 16-percentage-point drop since 2011. This was one of the lowest levels of support for democracy recorded in 34 countries surveyed in 2016/2018.

- Opposition to authoritarian alternatives weakened as well, to 69% against presidential dictatorship, 62% against one-party rule, and 57% against military rule. Rejection of apartheid held fairly steady at 74%.

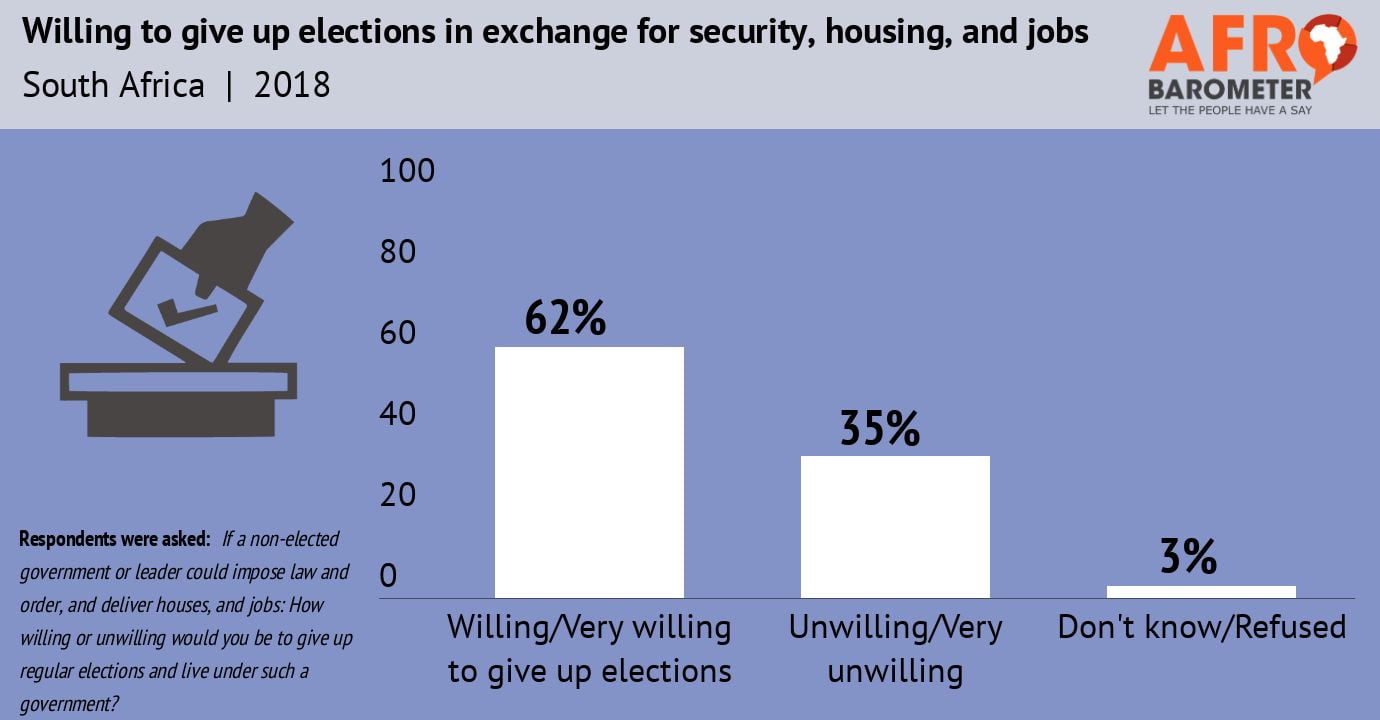

- A majority of South Africans still valued aspects of democratic governance, including 61% who favoured elections as the best way to choose leaders and 60% who said many political parties are necessary to ensure real choices for voters. But these proportions reflect declines of 16 and 9 percentage points, respectively, since 2015.

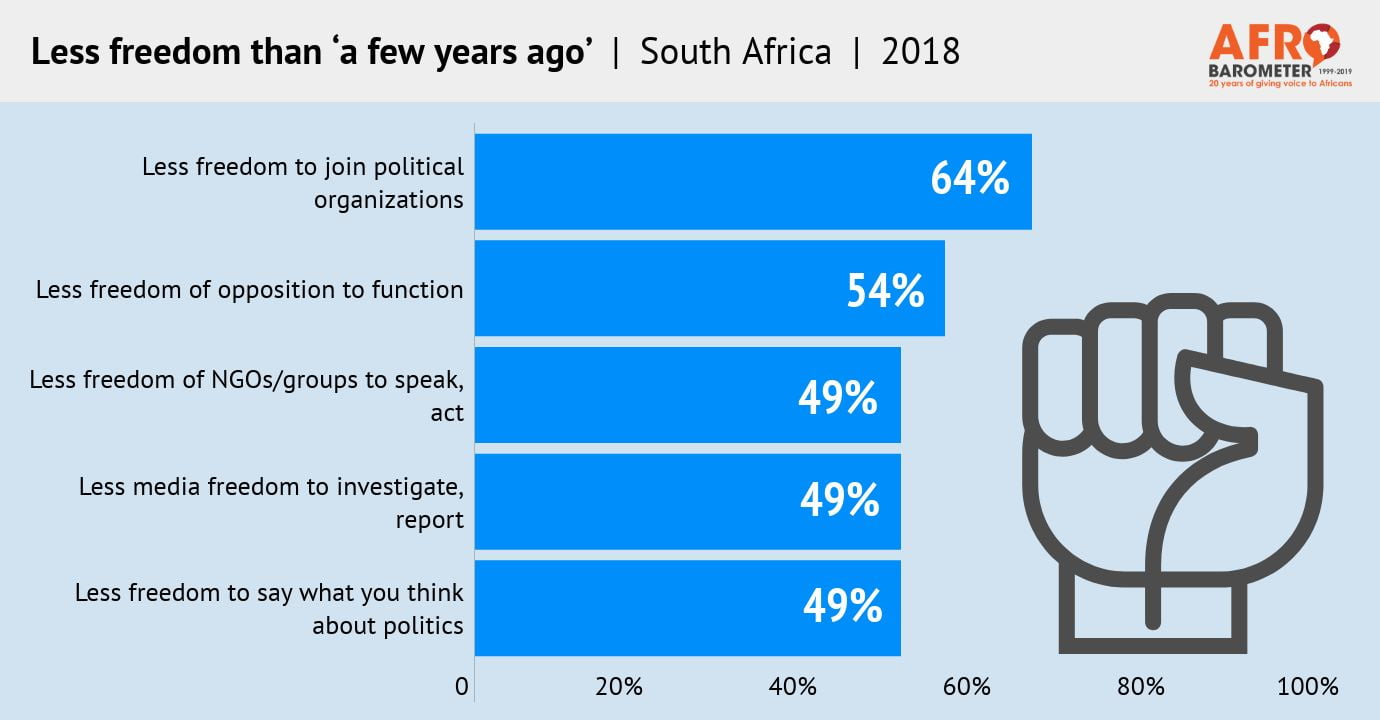

- South Africans perceived political space to be closing. Two-thirds (64%) said they now have less freedom than “a few years ago” to join any political organization they want, and about half saw declines in the freedom of the opposition to function (54%), of people to express their political views (49%), of the media to investigate (49%), and of independent organizations to advocate their views (49%).

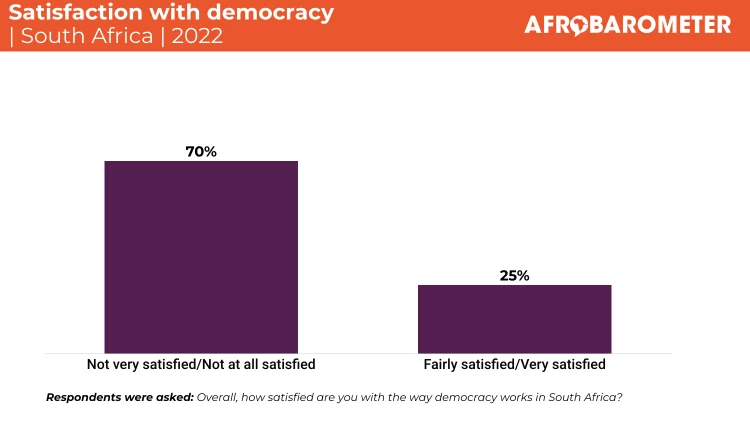

- Satisfaction with the way democracy is working has declined steadily, from 60% in 2011 to 42% in 2018 who said they were “fairly” or “very” satisfied.

Well into its third decade of democracy, South Africa entered 2020 with a limp. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic and its shutdowns began making most things worse (Roux, 2020), the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, also known as the Zondo Commission, was investigating large-scale corruption in government and private companies (Southhall, 2019). Lack of popular trust in the Public Protector, whose reports have been frequently contested in court, reached epic proportions as Parliament began steps to have her removed from office (Gerber, 2020). University protests dominated the news (Mahamba, 2020), and parliamentary disruptions and disorder remained a regular feature of the political landscape (Maqhina, 2020).

In March, the country slipped into an economic recession (Stats SA, 2020a), exacerbated by regular power outages thanks to Eskom, the failing national energy provider (Vollgraaff & Naidoo, 2020), and the financial drain of other unprofitable state-owned enterprises such as South African Airways, now under business rescue (Smith, 2020; Schulz-Herzenberg & Southhall, 2019). Unemployment rose to almost 40% (Dawson & Fouksman, 2020).

If South Africans were looking to political leaders for answers, they didn’t demonstrate that on Election Day 2019, which saw the lowest voter turnout (49% of the voting-age population) in any of the country’s six general elections since the end of apartheid in 1994 (Schulz- Herzenberg, 2019).

Are South Africans giving up on their democracy as a way to deliver both political goods (such as good governance and freedoms) and economic goods (such as poverty reduction and employment)1 that were part of post-apartheid expectations? Afrobarometer survey findings from mid-2018 show support for democracy weakening and acceptance of authoritarian alternatives growing. Many citizens see both freedoms and economic prospects as declining, and a solid majority remains willing to forego democratic elections in exchange for security, housing, and jobs. Findings suggest that South Africa was entering a democratic recession well before COVID-19.