- More than half (54%) of respondents said their household received a Child Support Grant during the previous year, while more than one-third (37%) benefited from an Old Age Pension. Respondents who are poor, less-educated, or live in rural areas were more likely to report receiving a social grant.

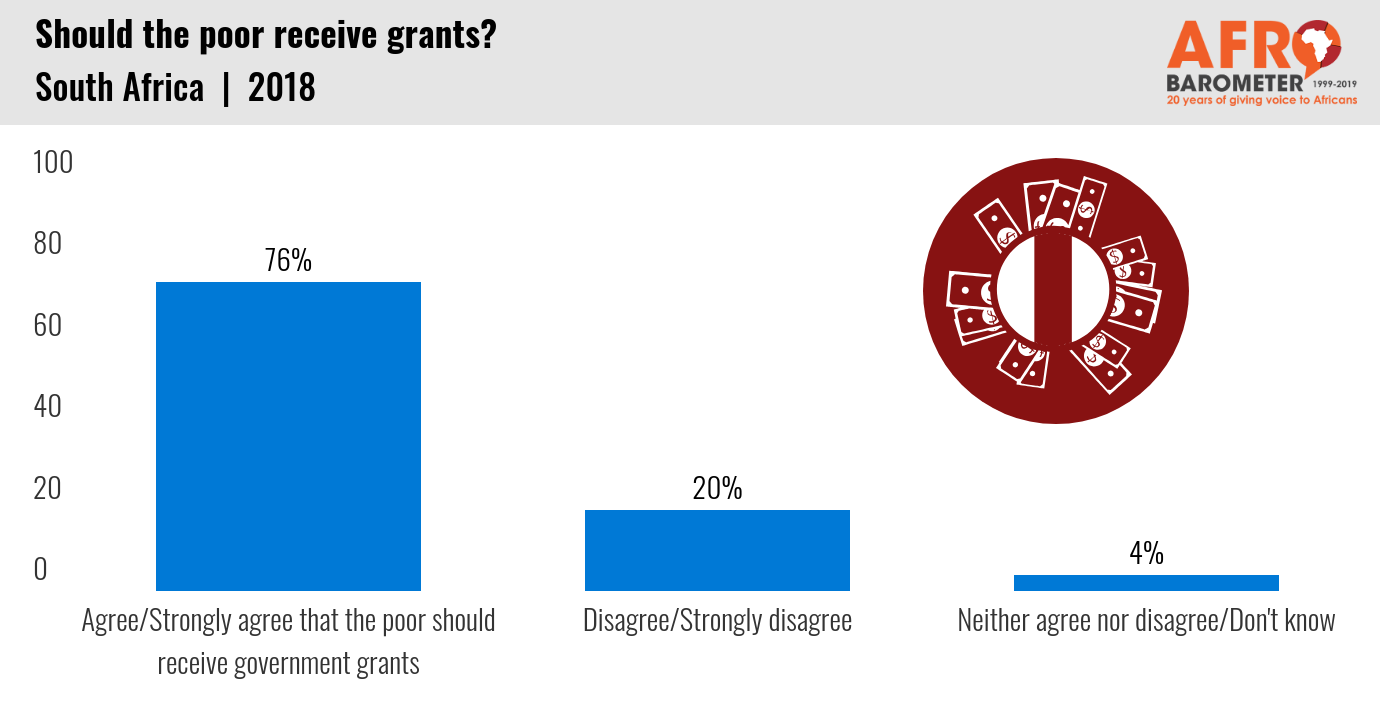

- Three-fourths (76%) of South Africans said the poor should receive grants from the state, and two-thirds (67%) believe it’s the state’s responsibility, rather than the family’s, to support the poor.

- Despite support for social grants, a majority (59%) of South Africans believe that reliance on the grants can demotivate recipients from looking for work. More than half (53%) said that physically able adults should work for money they receive from the state.

- When asked to compare two hypothetical economic systems, two-thirds (66%) of South Africans would prefer an economy with low wages and low unemployment over one with high wages and high unemployment. The vast majority (79%) believe it is better to have a low-paying job than to have no job at all.

In South Africa, “social grants” providing income support to poor households have a long history. More than 17 million citizens, almost one-third of the population, receive a cash transfer from the state each month (South African Social Security Agency, 2019). The largest social grant programs are the Child Support Grant (CSG), the Old Age Pension (OAP), and the Disability Grant. All target low-income households (Zembe-Mkabile, 2017).

In April 2020, to mitigate the economic shock of a national lockdown designed to curb the spread of COVID-19, the government introduced a R500 billion ($28 billion) fiscal support package that includes a six-month increase for social grants (National Treasury, 2020). A special COVID-19 Social Relief of Distress grant was introduced to help those who are ineligible to apply for other grants or claim unemployment insurance (South African Social Security Agency, 2020). Without measures like these, some economists were predicting that the coronavirus crisis could triple levels of extreme poverty in the country (Bassier, Budlender, Leibbrandt, Zizzamia, & Ranchhod, 2020).

But even before COVID-19 and the lockdown, social grants were an important part of the government’s response to high levels of poverty and unemployment (Statistics South Africa, 2017). According to Afrobarometer survey findings, lived poverty was on the rise in South Africa by 2018, and respondents identified unemployment as the most important problem that the government should address (Chingwete, 2019).

While social grants have proved to be effective at reducing the incidence of extreme poverty and preventing inequality from worsening (Sulla & Zikhali, 2018; Statistics South Africa, 2017), they have also drawn criticism as being unsustainable and capable of producing negative side-effects, such as dependency (Ferreira, 2017).

Outside of an emergency like COVID-19, do South Africans think that the poor should receive income support from the state? Or should they not rely on the state and instead work for their income? In an economy characterized by persistently high levels of unemployment (Sulla & Zikhali, 2018), would South Africans support changes to the labour market that created more jobs, even at the expense of lower wages?

Findings from the Round 7 (2018) Afrobarometer survey indicate that most South Africans are in favour of the state supporting the poor through cash transfers, even if many say that abled-bodied adults should work for their social grants. South Africans would also prefer low unemployment with low wages over high unemployment with high wages; the vast majority believe it is better to have a job at any wage than no job at all.