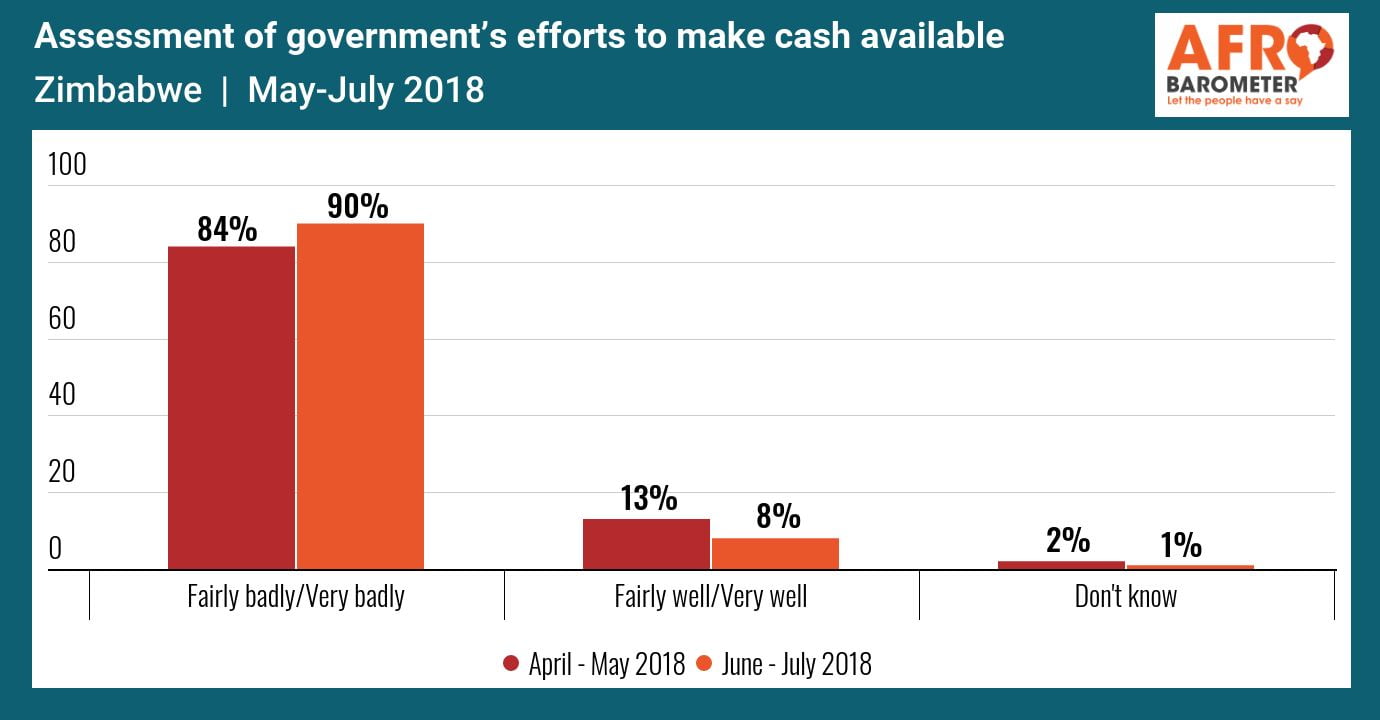

- Zimbabweans overwhelmingly gave their government poor marks when it comes to ensuring that cash is available. In April-May 2018, 84% said the government was doing “fairly badly” or “very badly” on this count; two months later, disapproval had risen to 90%.

- While Zimbabweans disapproved of the government’s efforts, they also expressed little trust in banks. Almost two-thirds (63%) of respondents said they trust local banks “just a little” or “not at all.”

- Four out of five Zimbabweans (80%) said they or a family member went without a cash income “several times,” “many times,” or “always” during the year preceding the 2017 survey. Even among post-secondary graduates, two-thirds (67%) reported this form of “lived poverty.”

- A majority of Zimbabweans (55%) said they depend at least in part on buying and selling goods to secure their livelihoods, while almost one in three (31%) rely to some extent on remittances – needs likely to require them to leave their homes and risk social interactions during a lockdown.

Zimbabwe has been on lockdown since March 30 to inhibit the spread of the new coronavirus,1 though the mining and manufacturing sectors have reopened under rules set by the World Health Organization and public health authorities (Mugabe, 2020). To help “vulnerable groups,” the government announced it had set aside $600 million for cash transfers to 1 million households and support to small businesses over the next three months (Kubatana.net, 2020).

In addition to difficulties facing many locked-down communities throughout Africa, such as crowded homes and settlements, lack of running water and sanitation, a weak health-care system, and inadequate economic reserves, Zimbabweans have a particular problem that hinders implementation of COVID-19 restrictions: cash.

Despite a largely informal economy where cash is king, chronic shortages of both domestic and foreign currency have plagued the country for years (National Public Radio, 2018). Well before the COVID-19 lockdown, long winding queues were a common feature at banks as people tried – often unsuccessfully – to withdraw cash. In stores and markets, a multi-tier pricing system penalizes customers who must use debit cards or mobile-money transfers, rather than cash, inviting a mark-up as high as 50%. Money-changing services that allow customers to convert electronic balances into cash draw crowds, even during a pandemic when social distancing is required (Matiashe, 2020). The interplay of an interim currency, a new Zimbabwean dollar introduced last November, and the U.S. dollar – outlawed last year for local transactions, then approved again during the COVID-19 period – adds to Zimbabweans’ exhausting and risky search for cash (Matiashe, 2020).

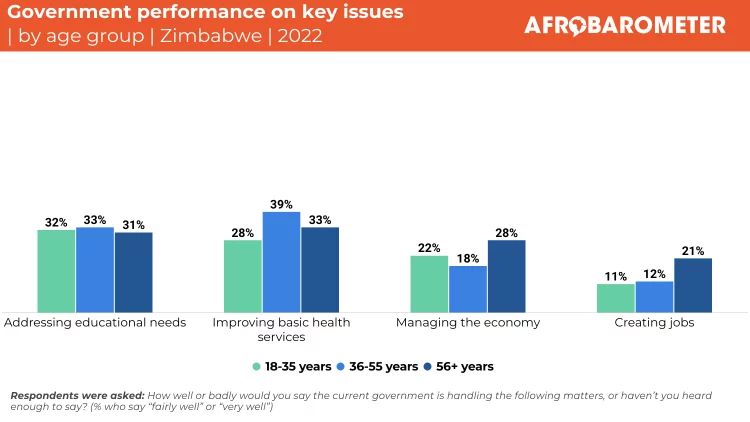

Afrobarometer survey findings from 2018 and 2017 reflect the cash-related vulnerabilities with which Zimbabweans entered the COVID-19 period. Citizens overwhelmingly said they consider the government ineffective in ensuring that cash is available. And most people expressed distrust of local banks. A majority of Zimbabweans frequently go without a cash income. Many depend for their livelihoods on buying and selling goods and on obtaining remittances from abroad – both of which would require them to leave their homes and risk social interactions during a lockdown. In short, Zimbabwe’s chronic cash shortages are likely to militate against the successful implementation of a national lockdown.