- As of mid-2018, management of the economy was by far the most important problem that Sudanese wanted their government to address, cited by 85% of citizens as a top priority.

- More than seven in 10 Sudanese (72%) described the country’s economic situation as “fairly bad” or “very bad,” and a majority (59%) expected things to get worse during the coming year. About half (48%) said their personal living conditions were bad.

- One-third (33%) of Sudanese said they had gone without enough food (33%) at least once during the year preceding the survey, while more than half had lacked sufficient clean water (57%), needed medical care (51%), and cooking fuel (68%). Frequent shortages of basic necessities were most common among rural residents, young citizens, those with little or no formal education, and residents of the Darfur region.

- Overall, more than three-fourths (77%) of Sudanese saw the country as headed in the wrong direction, a sharp increase from 47% in 2015.

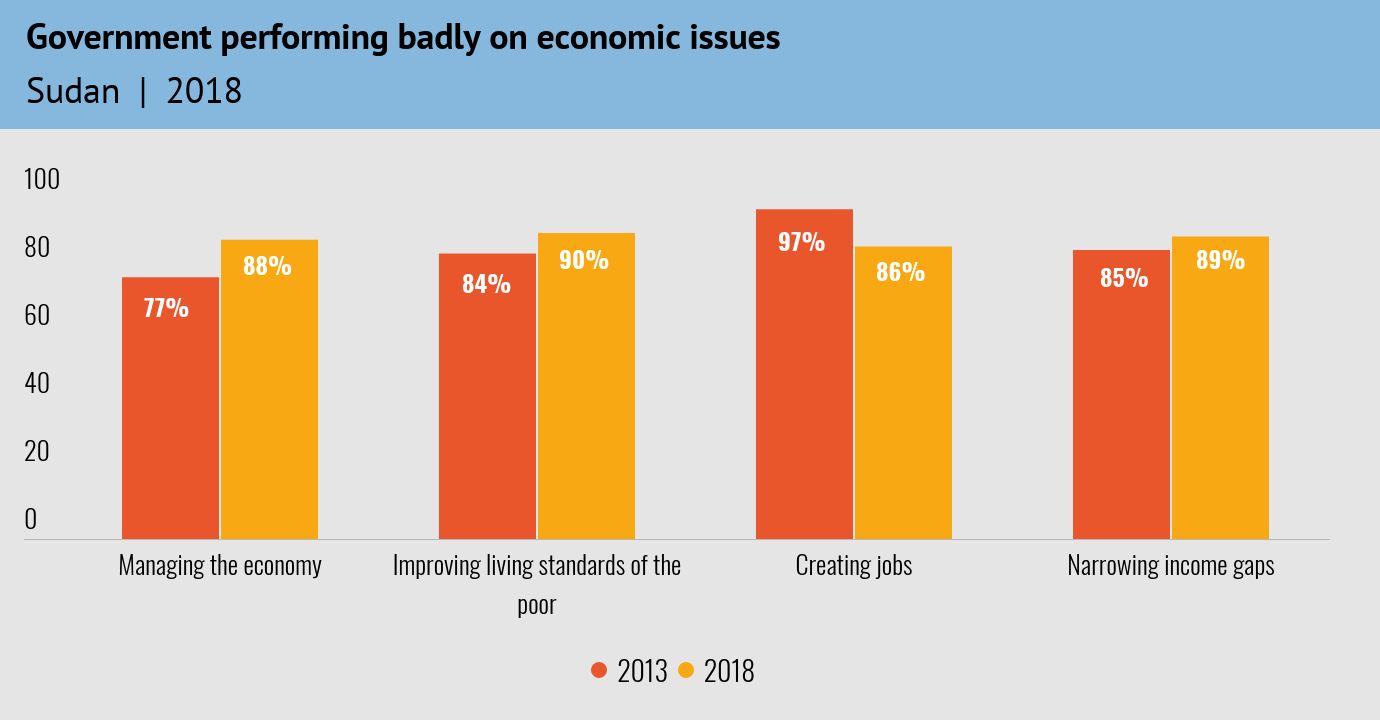

- About nine out of 10 Sudanese said the government was performing “fairly badly” or “very badly” in managing the economy (88%), raising living standards of the poor (90%), creating jobs (86%), and narrowing gaps between rich and poor (89%).

Sudan’s mass protests that ended the 30-rule of President Omar al-Bashir in April started last December with citizens unhappy about the high price of food (BBC News, 2019a).

And while the protest movement grew beyond its initial economic agenda to demand fundamental political change, one certainty amid the dramatic events in Khartoum is that the country’s deep-seated economic problems will still be awaiting solutions by whichever military or civilian leadership take up the reins.

Despite long-standing government and international anti-poverty initiatives (Siddig, El-Fatih, & Fareed, 2016; Food and Agriculture Organization, 2015), poverty remains a central reality for many Sudanese, and recent economic developments have offered little cause for optimism. Sudan is one of the least developed countries in the world, ranking 167th out of 189 countries in the 2017 Human Development Index ranking (United Nations Development Programme, 2017), with about one in five Sudanese suffering from extreme poverty (Cuaresma et al., 2018).

Causes of poverty in Sudan are manifold, ranging from political conflict, corruption, and drought to a bias in development initiatives in favour of the central riverine region and urban populations, to the detriment of rural areas and agricultural sector on which a majority of Sudanese depend (Yagoob & Zuo, 2016: Mohsin, 2002). A number of studies have also argued that structural adjustment programs implemented in the early 1990s, emphasizing economic liberalization and market mechanisms in the management of resources and economic activities, have increased poverty and unemployment and contributed to the disappearance of the middle class (Suliman, 2007; Randolph & Hassan, 1996).

The loss of oil-export revenues after the 2011 separation of South Sudan (Sharfi, 2014) and, until recently, U.S. economic sanctions (Siddig, 2010) added to economic pressures and scarcities of basic commodities.

Ordinary Sudanese were keenly aware of their economic predicament well before the dramatic political events of the past four months. In the most recent Afrobarometer public opinion survey, conducted in July-August 2018, citizens were almost unanimous in citing economic management as their country’s most urgent problem that the government should address. A majority described economic and living conditions as bad, and only a minority saw hope for the immediate future. Most saw their country as going in the wrong direction and gave their government negative marks on handling the economy, improving living standards, and narrowing gaps between rich and poor.