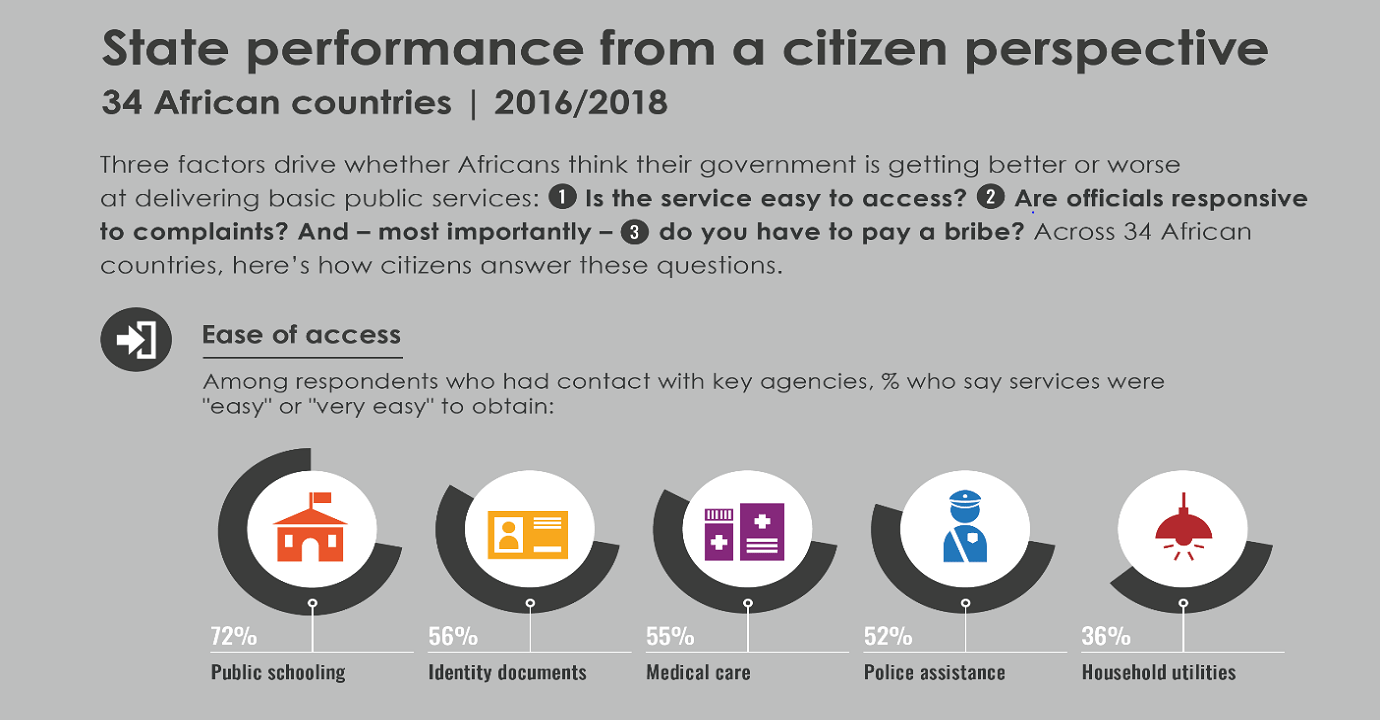

- On average, majorities of Africans report that access to most public services is “easy.” This positive assessment holds true for public education, identity documents, medical care, and assistance from the police. The main exception is access to household utilities, which are regarded as more “difficult” to obtain.

- In general, service delivery is seen as quite timely; on average, slightly more people report receiving services after “short” rather than “long” delays. But citizens disagree over the timeliness of police assistance; when compared with other services, police assistance is more likely to occur either “right away” or “never.”

- On average, a majority of Africans say that the treatment they receive from public officials is courteous. But about two in 10 report that interactions with public officials are “not at all respectful.”

- Overall, Africans are more likely to see improvements than deterioration in state delivery of key public services. But on average fewer than one in five citizens see simultaneous improvements in the performance of all three of the state agencies charged with public safety, education, and medical care.

Africa has long been characterized as a continent of strong societies and weak states (Migdal, 1988; Chickering & Haley, 2007; Henn, 2016). This image suggests that, compared to an informal sector rich in networks of self-help, mutual aid, and private entrepreneurship, public sector institutions are ineffective at getting things done. As a set of formal structures imported during colonial rule, the centralized state for decades remained “suspended in mid-air” – that is, above society – with limited aptitude to address the everyday needs of ordinary Africans (Hyden, 1983; Boone, 2006). Recognizing this impediment, policy makers have often subcontracted essential public services to non-governmental entities, private businesses, or public-private partnerships. Especially where the state has collapsed, such nonstate actors often step in and assume responsibility for the provision of “public” services (see for example Titeca and de Herdt (2011) on education in the Democratic Republic of Congo).

There has, however, been a steady expansion in public service delivery across most of Africa, especially with respect to public education and health care, along with piecemeal improvements in bureaucratic governance (Levy & Kpundeh, 2004; Fjelstad & Moore, 2008). By 2011, according to World Bank data (2018), almost three-quarters of boys and two-thirds of girls in sub-Saharan Africa completed primary school. Three out of four children were immunized against measles. Almost half of all births were attended by skilled personnel. Even where the state has collapsed, the idea of public provision remains potent (Lund, 2006). State agencies – both centralized and decentralized – continue to be the main point of service contact for most Africans.

How well are African states performing in delivering public services that citizens say they want?

Related content