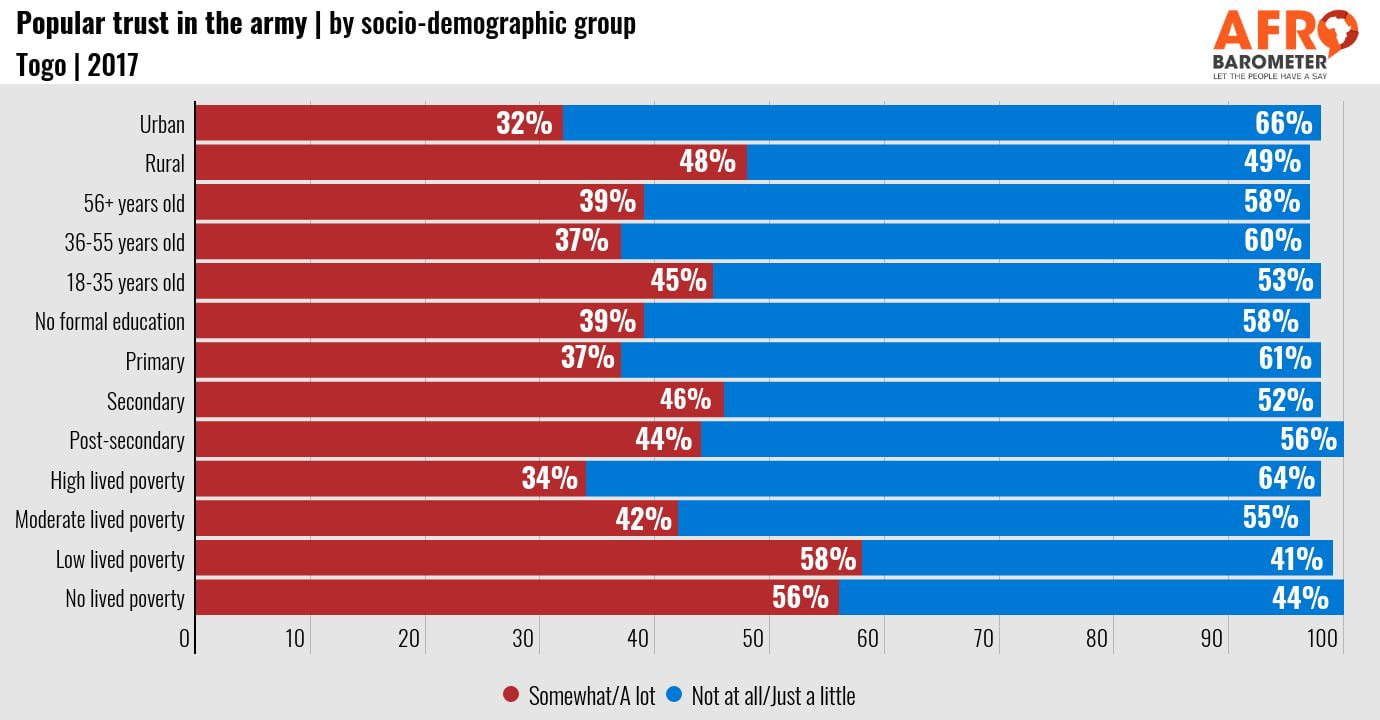

- Four in 10 Togolese (42%) say they trust the army “somewhat” or “a lot,” while a majority (56%) express only “a little” or no trust at all.

- Trust in the military is lower than average among urban residents, the less educated, and the poor, as well as among members of the Mina, Ouatchi, and Ewé ethnic groups.

- Fewer than half of respondents believe that the armed forces “often” or “always” protect the country from external and internal security threats (48%) or receive the equipment and training they need to be effective (44%).

- On broader questions of security, a majority (58%) of Togolese say they fear political intimidation or violence during election campaigns at least “a little bit,” including 28% who say they fear it “a lot.” The proportion of citizens who express no such fear declined from 47% in 2014 to 41%

- A majority (59%) of Togolese say the government should have the right to impose roadblocks and curfews when public safety is threatened

In Togo, the military is a very influential political actor. In 1967, a military coup installed Eyadema Gnassingbé as president, and he held power until his death in 2005. Immediately after his death, Eyadema’s son, Faure Gnassingbé, was declared president with the support of the Army. He resigned under regional pressure but ascended once more to the office after winning the April 2005 election, which was judged “free and fair” by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) but led to violent clashes that were quelled by the Togolese Armed Forces (Venkatachalam, 2017; Wong, 2017). The military’s proximity to executive power has long been decried by opposition parties, who charge that the armed forces have a stranglehold not just on government authority but even on prominent financial institutions in Togo (IRIN, 2005).

Key to the military’s close relationship with power is its ethnic makeup, consisting mainly of members of the president’s ethnic group, the Kabyè tribe from the North (Venkatachalam, 2017). At the time of the military coup in 1967, the dominant ethnic group in Togolese politics was the Ewé, who held about 70% of cabinet positions. Since the coup – which was led by a Kabyè military colonel – the Kabyè have dominated the political landscape, despite making up only 13% of the population (Crux, 2018).

Amnesty International has criticized the Togolese security forces for excessive use of force against protesters, journalists, and political opposition members. Under Faure Gnassingbé, the army has been accused of aggressively seeking out media outlets that show any sign of political dissent (Amnesty International, 2017a). In many forums over many years, the Togolese government has publicly expressed a commitment to curbing human-rights abuses by the security apparatus, but it has produced little evidence of any real effort beyond rhetoric (Amnesty International, 2017b).

Given the military’s controversial domestic role, how do Togolese citizens see their military? Findings from the most recent Afrobarometer survey show that fewer than half of Togolese trust the army, think it effectively protects the country, and say it acts with professionalism and respect for citizens’ rights – all assessments marked by strong ethnic, regional, and socioeconomic cleavages.

Related content