- By a 2-to-1 margin, Zimbabweans say that information held by public authorities is not only for use by government officials but rather should be shared with the public. More-educated citizens are more likely to support the public’s right to government information.

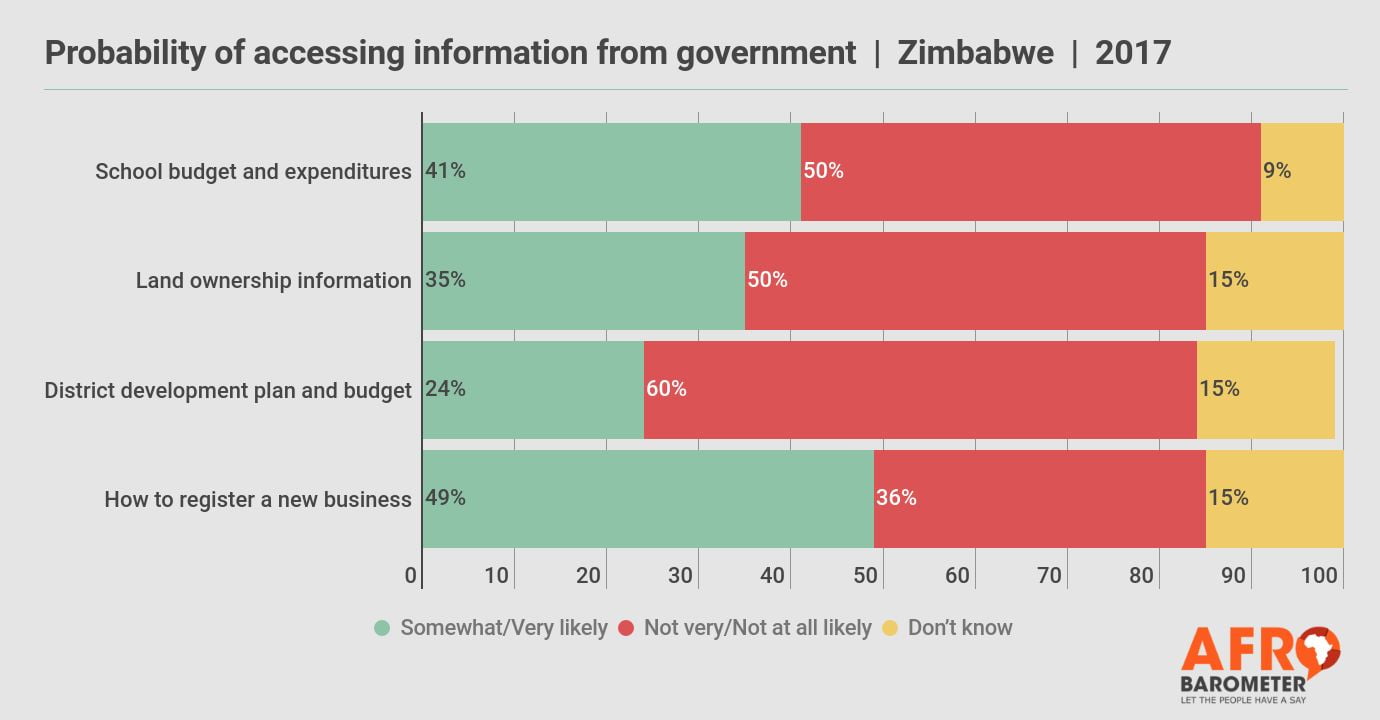

- But many Zimbabweans doubt they could actually access such information from local authorities. Fewer than half think it is “somewhat likely” or “very likely” that they could find out from their local council how to register a new business (49%), obtain information from a local school about school budgets and expenditures (41%), find out from the district land office who owns a piece of land in their community (35%), or get information about their district’s development plan and budget from their local council (24%).

- Rural residents have somewhat greater confidence than their urban counterparts in their ability to obtain such information. Surprisingly, respondents’ gender, age, and education level make little difference, except that more-educated citizens are more likely to think they could probably get the information they need to register a new business.

Information is the lifeblood of political accountability. Without reliable, timely information, citizens are unable to evaluate and constructively engage with what their government is doing. If such information is absent, willfully denied, physically inaccessible, or not available in a format that is understandable to users, public accountability is undermined (ANSA-EAP, 2017).

Citizens’ right to information is recognized in international human-rights standards and treaties, including the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights African Freedom of Information Centre, 2014). Even so, some observers argue that access-to-information laws are being used to clamp down on the free flow of information instead of creating a conducive environment for citizens to access public information (African Freedom of Information Centre, 2017) In Zimbabwe, the Access to Information and Protection of Privacy Act (AIPPA) is often criticized for limiting access to information.

Afrobarometer’s 2017 survey finds that a majority of Zimbabweans endorse the idea that information held by public authorities is not just for use by the government but should be shared with the public. However, it also finds widespread skepticism about whether citizens can actually access such information at local levels, such as school budgets and district development plans.