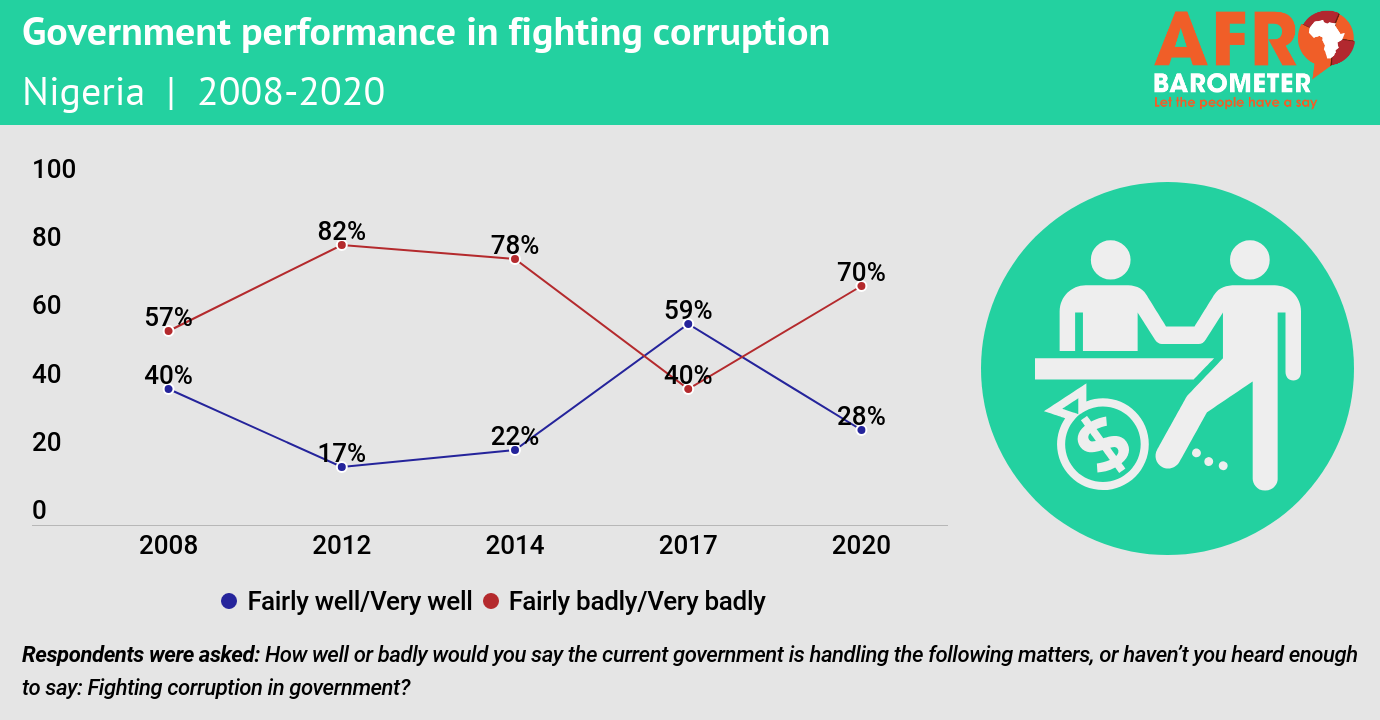

- Six in 10 Nigerians (59%) say the government is performing “fairly well” or “very well” in fighting corruption – almost three times as many as gave a thumbs-up in 2015 (21%). However, Nigerians are evenly split (43% each) as to whether corruption has increased or decreased over the past year.

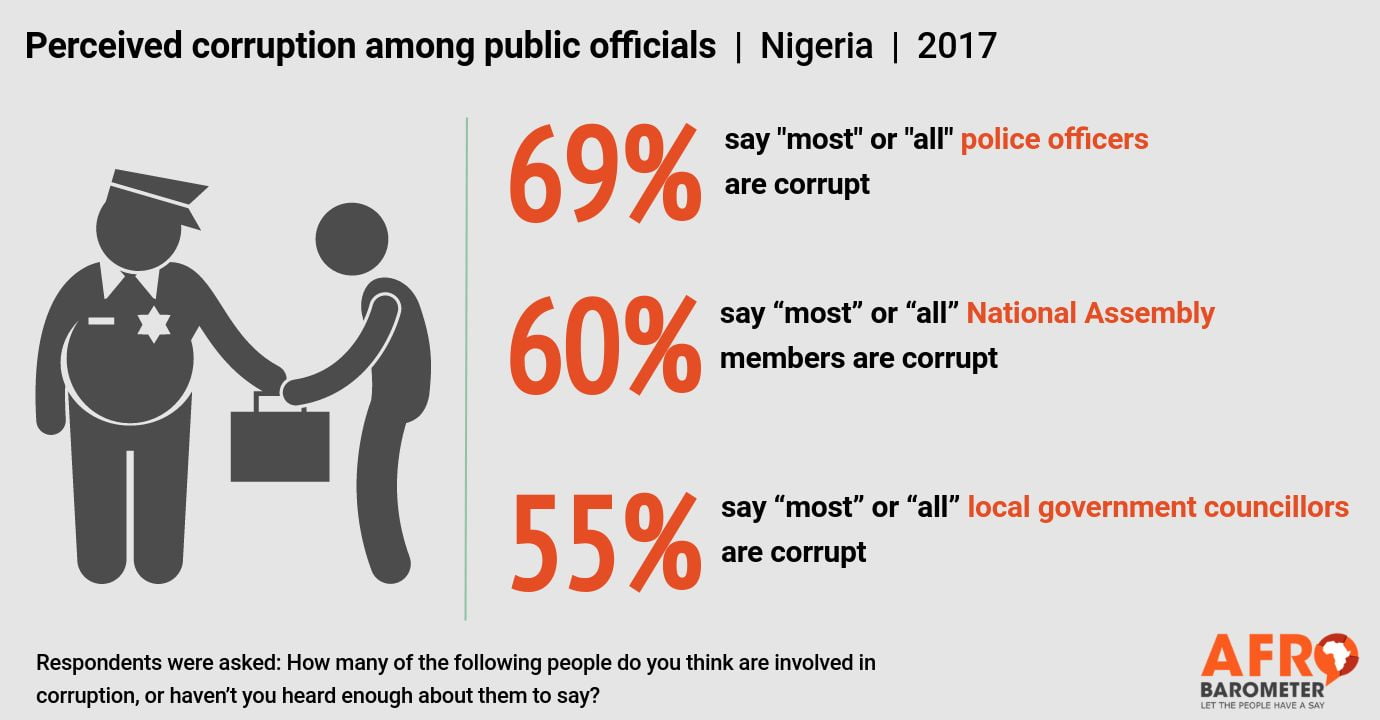

- Nine out of 10 Nigerians say at least “some” public officials are corrupt. The police are seen as most corrupt; 69% of citizens say “most” or “all” police officials are corrupt, followed by members of the National Assembly (60%) and local government councillors (55%). High perceptions of corruption are matched by high public mistrust.

- Among Nigerians who sought key state services last year, large proportions say they paid bribes to receive police assistance (68%), avoid problems with the police (44%), or get government documents (38%), water or sanitation services (34%), or medical care (20%).

- Even though a majority (54%) of citizens agree that ordinary people can make a difference in the fight against corruption, more than three-fourths (77%) fear retaliation should they report an incident of corruption.

- Large majorities believe it is “very likely” or “somewhat likely” that rich people can pay bribes or use personal connections to register land not owned by them (80%), avoid going to court (80%), and evade taxes (78%).

Since Muhammadu Buhari became president in May 2015, Nigerians have witnessed a series of investigations into alleged corruption by past and present government officials, including high-profile cases involving the former minister of petroleum and a former national security adviser (Al Jazeera, 2017; Vanguard, 2016; Oyibode, 2017). Buhari’s anti-corruption campaign has not spared members of his own government: The secretary to the Government of the Federation and the director of the Nigeria Intelligence Agency were sacked and are being investigated on corruption charges (Kazeem, 2017; Gramer, 2017). This seems a departure from the norm of anti-corruption campaigns that target only members of the opposition or former governments.

Several steps have been taken to embed anti-corruption safeguards into government frameworks and institutions. In 2016, the Nigerian government announced a whistleblower policy (Proshare, 2017) aimed at exposing corruption and fighting financial crimes. Nigeria also joined the Open Government Partnership (OGP) (Nigeria Bulletin, 2017) – a symbolic and significant step toward increased transparency and accountability. Continued involvement in OGP offers the government a mechanism for comparing its practices to international standards, a benchmark that can be an effective tool in holding the government accountable (Igbuzor, 2017).

Despite these efforts, which have earned Buhari recognition from the African Union as an anti-corruption champion, the nation still ranked 136th (out of 176 countries) on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International, 2017) and continues to grapple with corruption scandals amid calls for fiscal transparency and accountability in governance.

Afrobarometer’s latest survey in Nigeria indicates that public perceptions of the government’s fight against corruption have improved dramatically. Perceived corruption in the public sector, however, remains high, with the police perceived as the most corrupt and least trusted by citizens. Although most Nigerians think they can make a difference in the fight against graft, many still fear retaliation should they report an incident of corruption.

Related content