- Two-thirds (65%) of Nigerians favour democracy as the best form of government, a decline from 69% in 2012, and one in five (21%) say non-democratic forms can sometimes be preferable.

- While majorities reject non-democratic alternatives, 15% approve of military rule, 11% support one-party rule, and 9% approve of one-man rule.

- Nigerians show relatively weak support for checks and balances to ensure that public officials perform their functions appropriately, and most respondents do not see voters and their ballots as playing leading roles in ensuring accountability.

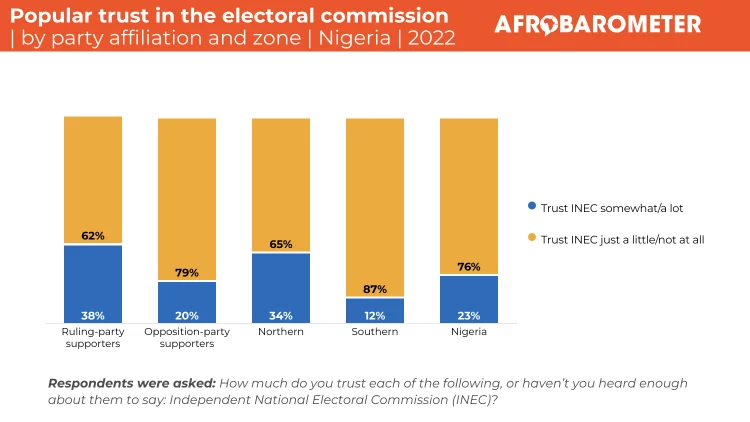

- Ahead of the elections, key political office holders receive weak approval ratings on their performance, and public perceptions are characterized by low levels of trust and high levels of perceived corruption.

Nigeria’s 2015 general elections, delayed by six weeks because of scaled-up military operations against terrorism, are likely to be the most competitive in the country’s history (see Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 11) . The Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) has used the extra time to distribute more voter cards and complete other preparations. In the tense build-up to the elections, this new analysis of Afrobarometer survey data collected in December 2014 takes the democratic pulse of Nigerians as they get ready to head to the polls.

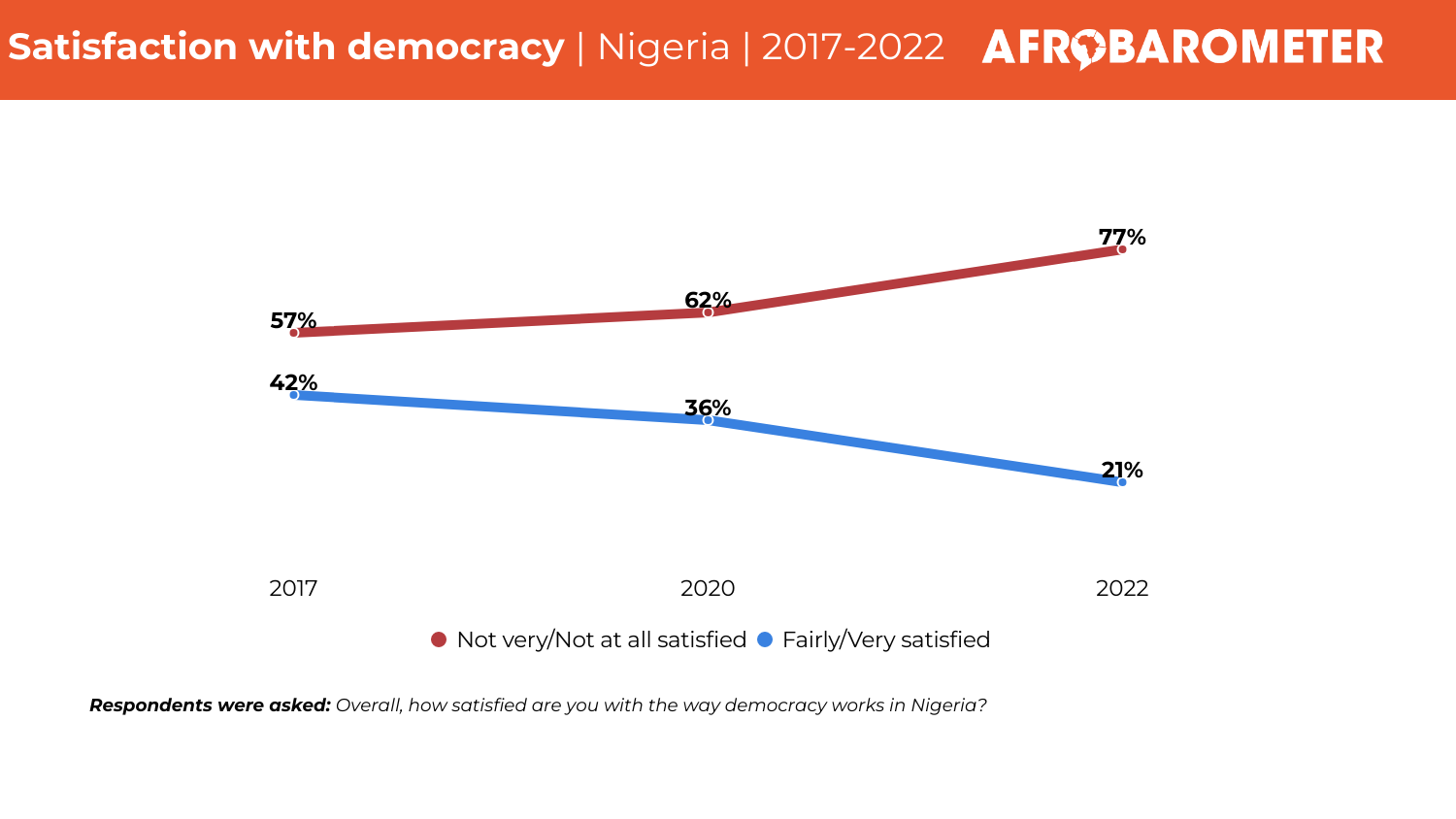

Focusing on attitudes toward democracy and accountability, the analysis finds that while most Nigerians embrace the concept of democracy and reject other forms of government, significant proportions of the population express support for non-democratic practices, such as military rule or an authoritarian president who is above the checks of Parliament and the courts. Public dissatisfaction with how democracy is working in Nigeria and with the performance of their elected leaders is high. Many Nigerians believe that public institutions and office holders can serve as checks on each other, but they do not see voters as playing a leading role in holding political officials accountable. Levels of citizen trust in institutions and leaders vary, in parallel with perceptions of office-holder corruption, suggesting that addressing corruption is likely to be a key to building public trust in elected offices and government agencies.

Related content