- Crime/insecurity continues to rank second among the most important problems that South Africans want their government to address.

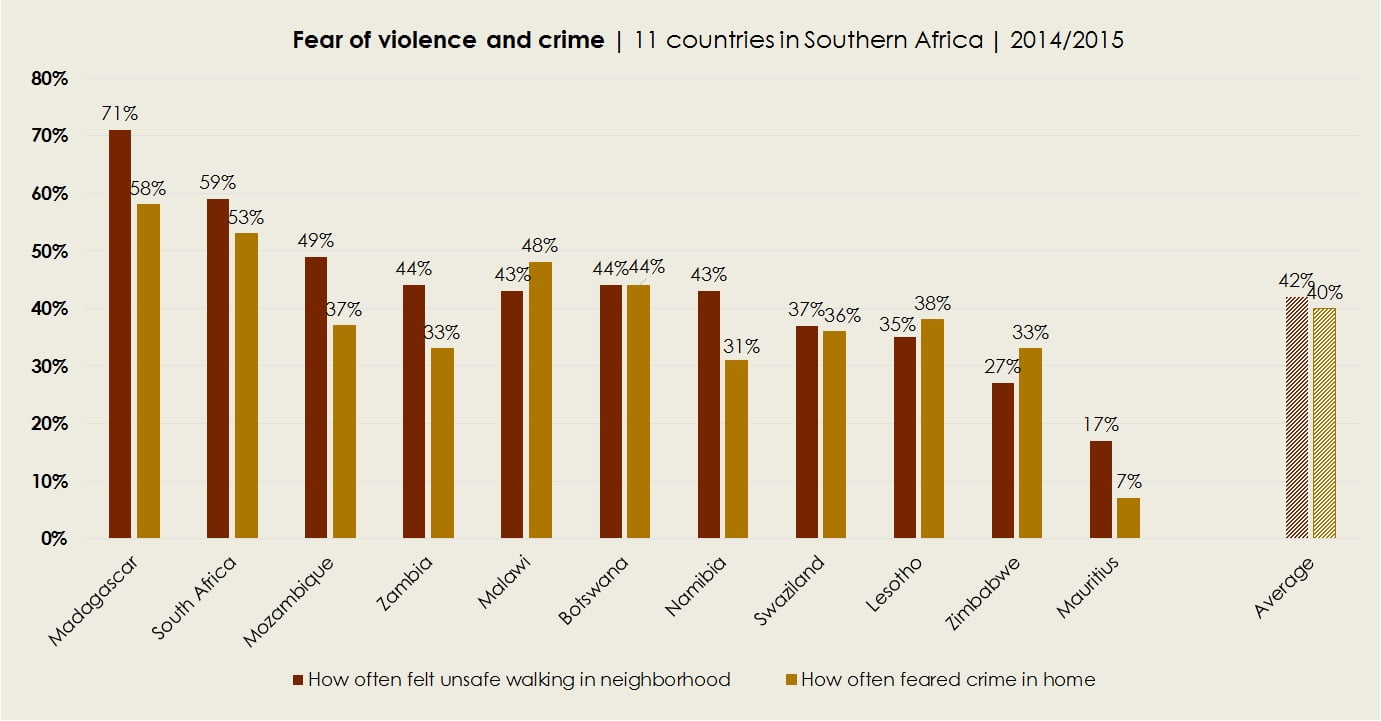

- Majorities of South Africans say they felt unsafe walking in their neighbourhood (60%) and feared crime in their homes (53%) at least once during the previous year. Across 11 countries surveyed in the Southern Africa region, South Africa ranks second after Madagascar in the proportion of citizens who report feeling unsafe and fearing crime.

- Substantial proportions of citizens report having experienced theft in their home (28%) and physical attacks (13%) during the preceding year. Experience of crime is more common amongst Indian South Africans than other racial groups and amongst poor citizens compared to their wealthier counterparts.

- A growing number of South Africans say that people are “often” or “always” treated unequally under the law (63%, up from 49% in 2011) and that officials who commit crimes “often” or “always” go unpunished (68%, up from 56%). Across 11 surveyed countries in Southern Africa, South Africans are the most likely to perceive unequal treatment under the law.

- Fewer than half (45%) of South Africans say they trust the police “somewhat” or “a lot” (down from 49% in 2011), and public trust in courts of law dropped by 10 percentage points, to 56%.

Though an economic magnet, South Africa is still grappling with serious problems of crime and violence. Both Statistics South Africa and the government’s 20-year review (Presidency of the Republic of South Africa, 2015) reveal significant progress, but both also confirm continued disturbingly high levels of violence. The Victims of Crime Survey 2015/16 (Statistics South Africa, 2016) found that while the number of South African households that experienced housebreakings and home robberies declined between 2010 and 2016 (from 6.8% to 5.7%), more South Africans perceived crime to have increased (41.7% in 2015/2016 vs. 31.2% in 2010).

Moller (2005) notes that crime has long been a problem in South Africa and indeed increased steadily prior to the 1994 transition, at a time when the police force was focused on quelling political unrest and neglected criminal activity. Gould (2014), a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, argues that “it should come as no surprise that crime and violence remain disturbingly high in South Africa. What is surprising is that there isn’t even more crime and violence, considering how we have dealt with our violent past, that we have increasing poverty and inequality, and have failed as a country to secure confidence in and respect for the rule of law.” The post-1994- government took steps to address crime and violence, including the 1996 National Crime Prevention Strategy and the 1998 white paper on safety and security, and made crime reduction a strategic priority of its National Development Plan (South Africa National Planning Commission).

Despite these efforts, South Africa ranks among the world’s most violent countries, according to the Global Peace Index (Institute for Economics and Peace, 2016): 126th out of 163 for overall peacefulness and 184th out of 193 based on homicide rates and perceptions of safe walking. The index report notes that “a weak and mistrusted security apparatus” may make it hard for the country to build on its progress going forward (p. 19). In addition to its devastating impact on individuals, crime and violence carry a high economic price for the country. The Institute for Economics and Peace estimates the economic impact of violence containment in South Africa at $66.7 billion (R989 billion) for the past year and pegs the national cost of violence in South Africa at 19% of the gross domestic product (GDP) – the 16th-highest rate in the world (average 13% of GDP) (BusinessTech, 2016).