- Only 37% of Togolese say they trust their courts “somewhat” or “a lot” (Figure 1) – the sixth-worst rating among 36 surveyed countries and well below the West Africa1 average of 48%. This puts courts roughly in the middle when compared with other key institutions, somewhat below the police and the army (both 42%) (Figure 2). Even religious leaders are trusted by just two-thirds (67%) of Togolese.

- Almost half (48%) of Togolese say that “most” or “all” judges and magistrates are corrupt, the seventh-worst rating among 36 countries, and significantly worse than the averages for West Africa (40%) and the 36 surveyed countries (33%) (Figure 3).

- About one in nine Togolese (11%) say they had dealings with the court system during the five years preceding the survey (2009-2014), a slightly lower contact rate than average (13%) across 36 countries (Figure 4).

- When asked why people might not take cases to court, Togolese cite the expense (22%) and the perception of the courts as favouring the rich and powerful (17%) and not providing fair treatment (17%) (Figure 6). They also say that many people don’t trust the courts (16%) and fear the consequences of pursuing a case in court (15%).

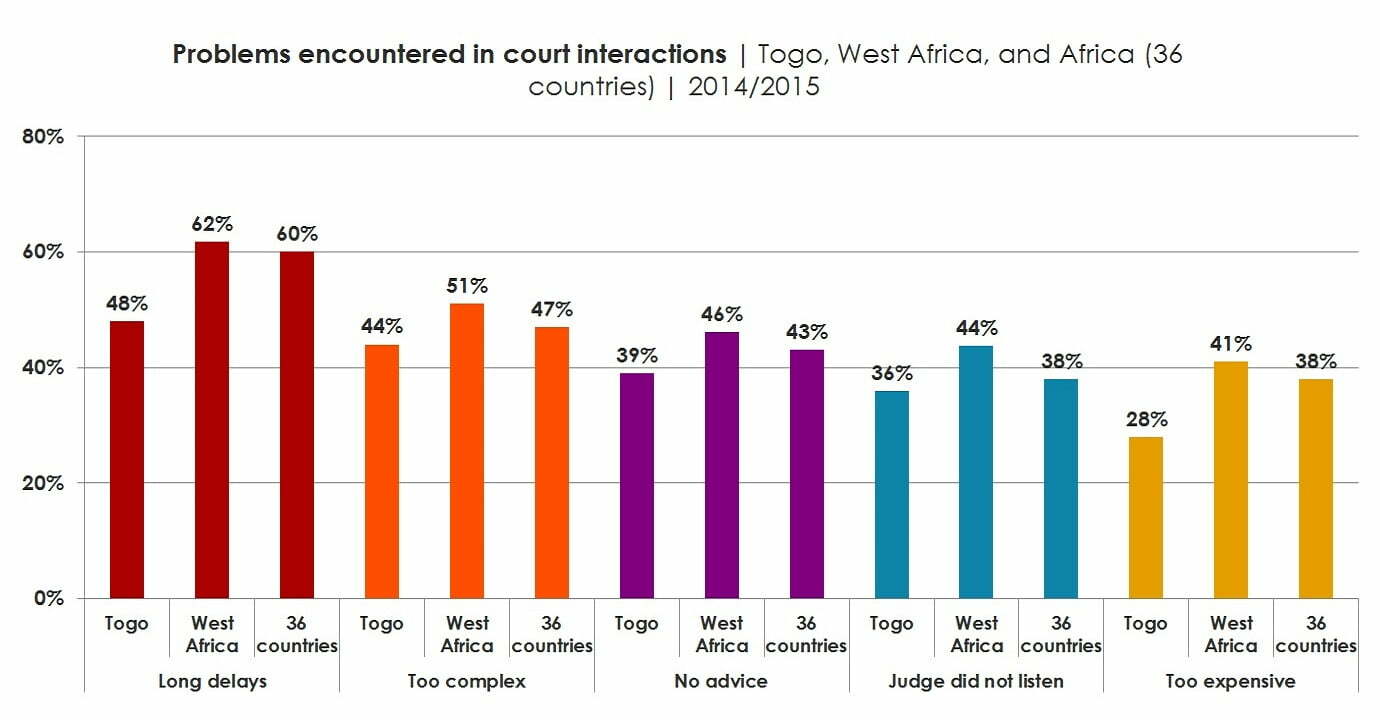

- Respondents who had interacted with the courts during the preceding five years were asked which problems they encountered. Long delays were the most common problem, cited by 48% of Togolese. The complexity of the legal system (44%), lack of legal counsel (39%), inattentive judges (36%), and high costs (28%) were common experiences as well (Figure 7). The proportion of Togolese who report experiencing each of these problems is lower than the regional and continental averages.

International observers see Togo’s judicial system as suffering from heavy political influence by the presidency, including lengthy pretrial detention for political opponents and impunity for political friends (Freedom House, 2016; U.S. State Department, 2015).

Similarly, they largely see Togo’s Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission, established to deal with accusations of political violence between 1958 and 2005, as having fallen short of its objectives, leaving “victims who endured human rights abuses … disillusioned by the total impunity that yesterday’s perpetrators, still in power, continue to enjoy today” (United Nations Human Rights Office, 2012).

On the other hand, Togo’s government has taken steps in recent years to improve citizen access to the country’s legal system. These include the construction of new appeals court buildings in Lomé and Kara (a lower court building in Sokodé is on the way) and the renovation of court buildings in Aného and Atakpamé. Efforts to improve staffing have included revising the status of magistrates, court clerks, and bailiffs; increasing the number of magistrates and clerks; and establishing a training school for clerks. Finally, access has been facilitated through the creation of welcome, information, and orientation offices; legal clubs for prisoners; and a legal guide for defendants.

How do ordinary Togolese perceive their legal system and the access to justice it affords them? Core elements that define citizens’ access to justice include: 1) a supportive legal framework, 2) citizen awareness of their legal rights and responsibilities, 3) availability of legal advice and representation, 4) availability of affordable and accessible justice institutions, 5) the practice of fair procedures in those institutions, and 6) enforceability of decisions (American Bar Association, 2012).

Afrobarometer Round 6 surveys included a special module that explored individuals’ perceptions of the legal system, their access to it, and their experiences when engaging with it. (For findings across all surveyed countries, please see Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 39.)

Survey responses in Togo depict a judicial system marked by popular distrust – a striking illustration of the observation by Bishop Nicodème Barrigah-Benissan, president of the Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission, that “the biggest victim of our recurring conflict is certainly trust that we’ve totally banished from our interpersonal relationships. The Togolese seem to have erected distrust as an absolute principle” (United Nations Human Rights Office, 2012). In Togo, both lack of public trust in the courts and perceptions of corruption among judges and magistrates are well above average ratings across West Africa and across 36 African countries surveyed in 2014/2015. Among citizens who actually had contact with the courts, many complain of long delays, the system’s complexities, a lack of legal counsel, judges who wouldn’t listen, and high costs.

Related content