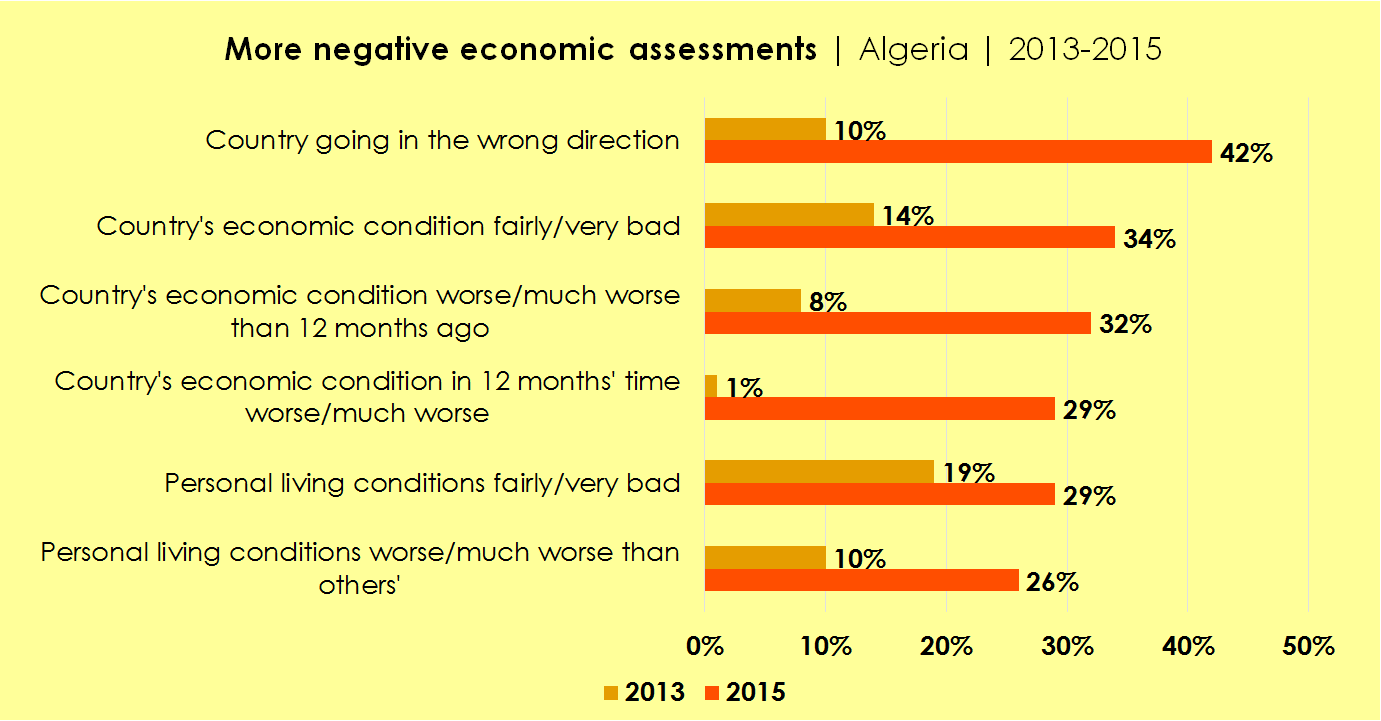

- Between 2013 and 2015, Algerians’ outlook darkened considerably, with a fourfold increase – from 10% to 42% – in the proportion of respondents who said the country was headed in “the wrong direction.”

- Similarly, citizens were far more likely than in 2013 to say that their country’s economic conditions were bad (34%, vs. 14% in 2013), that economic conditions had gotten worse during the previous year (32% vs. 8%), and that the economy would deteriorate within 12 months’ time (29% vs. 1%).

- Men, younger respondents, and poorer citizens were especially likely to be critical in their assessments of economic conditions.

- Almost two-thirds (63%) of Algerians said the government was doing a poor job of managing the economy, a 25-percentage-point increase from 2013. Assessments of government performance on other economic issues were also strongly negative, though slightly improved since 2013.

- Economic discontent was matched by negative perceptions of political leaders and the quality of elections. Majorities said leaders work to advance their own ambitions rather than the public interest (56%) and rarely listen to their constituents’ views. Only about two in 10 respondents said that votes in elections are always counted fairly (16%) and that elections work well to ensure that MPs reflect voters’ views (24%) and to enable voters to remove underperforming leaders (20%).

Six years after protests swept Northern Africa in the Arab Spring, Algeria entered 2017 with unrest in the streets. Like many other petro-economies, Algeria relies heavily on high state spending and subsidies. But in recent years, plummeting oil and gas prices have hit the county’s economy hard. Algeria generates about 95% of its export earnings from oil, and faced with dwindling revenues and reserves, the government has been tasked with reducing state spending by 9% in 2016 and another 14% at the beginning of this year (Falconer, 2017; Stratfor, 2017; Wrey, 2017). With the passing of a 2017 austerity policy that included cuts in state spending and subsidies and increases in value-added, income, property, and tobacco taxes, some protests turned violent, leading to arrests as shops and bank offices were looted (Falconer, 2017). As Carboni, Kishi, and Raleigh (2017) note, the number of recent protest events has already surpassed those of 2011, “raising concerns that local grievances may give rise again to wider collective actions,” with implications beyond Algeria, as Stratfor (2017) remarks: “Because Algerian stability is important to overall North African security, the protests bear watching.”

In comparison to Tunisia and Egypt, Algeria saw fairly weak support for the Arab Spring in 2011, and no regime change took place. But with an aging regime and an economic downturn, might Algeria return for a spring of change?

Afrobarometer survey findings in Algeria suggest that popular discontent is not merely a response to the most recent austerity moves but has been building for some time. Data collected in May-June 2015 show that Algerians were considerably more negative in their assessments of the country’s economic situation and their government’s performance than in 2013. Findings also raise questions about Algerians’ perceptions of elections as a solution to their problems: Most saw political party leaders as self-serving, few perceived the political opposition as a viable alternative, and few considered elections an adequate mechanism for replacing non-performing leaders and ensuring that the interests of the people are reflected.

Related content