- In September-October 2014, seven in 10 citizens (71%) said they trust the courts “somewhat” or “a lot” (Figure 1). This is the fourth-best rating among the 36 countries surveyed, well above the average of 53% and the East Africa1 average of 64%. The police could claim a similar level of public trust (74%) at the time. Most public institutions and leaders enjoyed even higher levels of public trust in Burundi, led by religious leaders (92%) and the army (90%) (Figure 2).

- Four in 10 Burundians (40%) say that “most” or “all” judges and magistrates are corrupt. This rating is about average for East Africa (39%) and somewhat higher than the average across 36 countries (33%) (Figure 3).

- About one in six Burundians (17%) had dealings with the courts in the five years preceding the survey (2009-2014), the eighth-highest contact rate among the 36 surveyed countries (Figure 4).

- Men are twice as likely as women to have contact with the courts, 23% vs. 11% (Figure 5). Respondents with a primary-school (19%) or higher education (23%) also have more dealings with the courts than those with no formal education (12%). The youngest (18-25 years old) and poorest respondents have slightly lower levels of contact with the courts than their older and less-poor counterparts

- When asked why people might not take cases to the courts, Burundians say that the courts are too expensive (31%), that judges or court officials will demand money (16%), that the courts favour rich and powerful people (16%), that they don’t expect fair treatment (14%), and that they don’t trust courts (14%) (Figure 6).

After Burundi emerged from civil war in 2005, one of the government’s priorities was to develop a professional and credible judicial system. Yet five years on, a Human Rights Watch report (2010) documented “Mob justice in Burundi: Official complicity and impunity,” and subsequent reports have continued to highlight extra-judicial killings, torture, and disappearances blamed on Burundian security forces and political gangs (Human Rights Watch, 2016).

Perpetrators have enjoyed near-impunity from a weak judicial system pressured into silence or collaboration (Human Rights Watch, 2016). A notable example was described by former Constitutional Court Vice President Sylvère Nimpagaritse, who after fleeing to Rwanda said the high court’s judges had come under “enormous pressure and even death threats” to rubber-stamp as legal a disputed third term for President Pierre Nkurunziza in 2015 (Guardian, 2015). The court’s decision to allow Nkurunziza’s candidacy became a flashpoint for popular protests and a symbol of a judicial system captured by an increasingly authoritarian government.

Against this background of mob justice and ineffectual courts, how do Burundians perceive their access to justice? Core elements that define citizens’ access to justice include: 1) a supportive legal framework, 2) citizen awareness of their legal rights and responsibilities, 3) availability of legal advice and representation, 4) availability of affordable and accessible justice institutions, 5) the practice of fair procedures in those institutions, and 6) enforceability of decisions (American Bar Association, 2012). Afrobarometer Round 6 surveys included a special module that explored citizens’ perceptions of the legal system, their access to it, and their experiences when engaging with it. For findings across all surveyed countries, please see Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 39

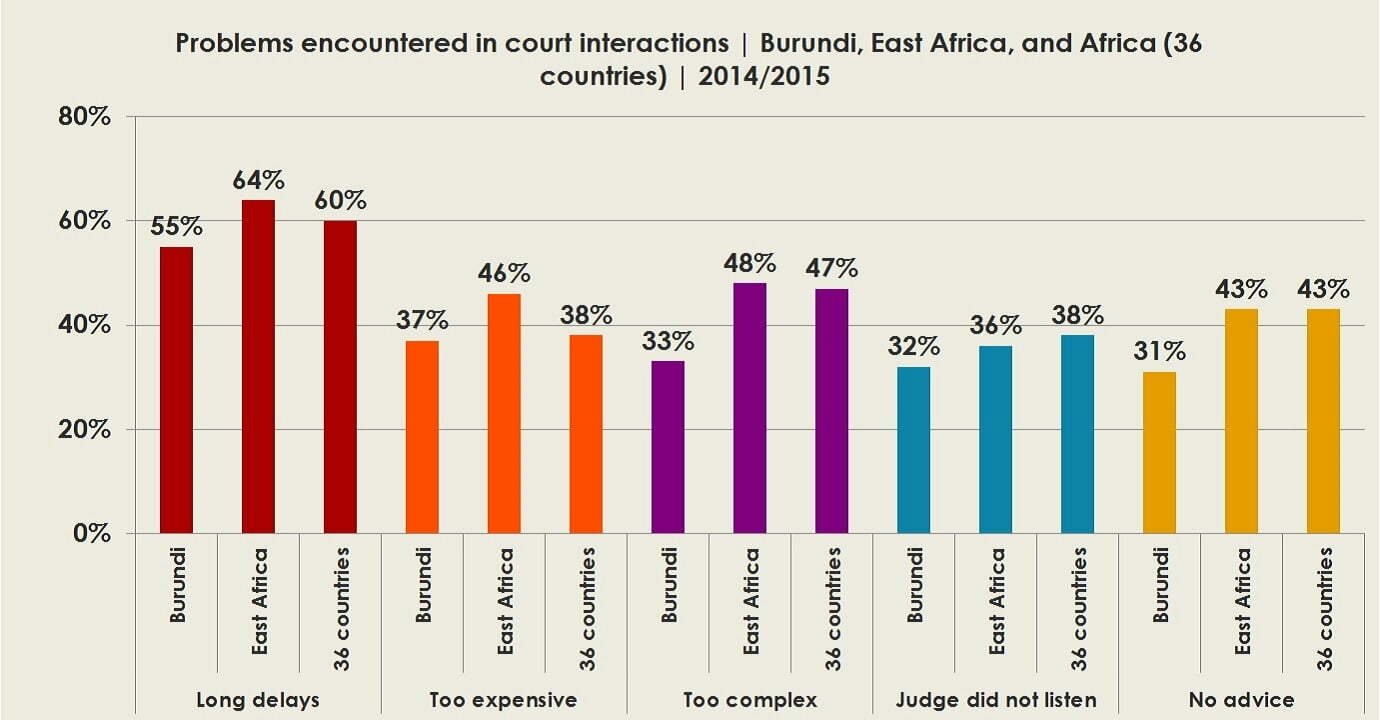

In Burundi, Round 6 data were collected in September and October 2014 – months before the constitutional crisis over Nkurunziza’s third term and the discredited 2015 presidential election, but years into the country’s nightmare of security abuses. Would respondents’ views be different now? At the time, Burundians’ levels of trust in and contact with the courts were among the highest among 36 African countries surveyed in 2014/2015. While many respondents cited significant problems with the courts – including widespread corruption, long delays, and high costs – Burundians were somewhat less likely than other Africans, on average, to complain of encountering difficulties or having to pay bribes when they sought assistance from the courts.

To the extent that these findings reflect a popular endorsement of the court system, one possible interpretation might be citizens’ preference for formal courts and the rule of law over informal and extra-judicial methods of dispensing “justice.”

Related content