- Citizens’ perceptions that Egypt is a democracy have doubled since 2013. Four in 10 respondents now say their country is “a full democracy” (11%) or “a democracy with minor problems” (31%) – about equal to the proportion who see it as “not a democracy” (14%) or “a democracy with major problems” (28%)

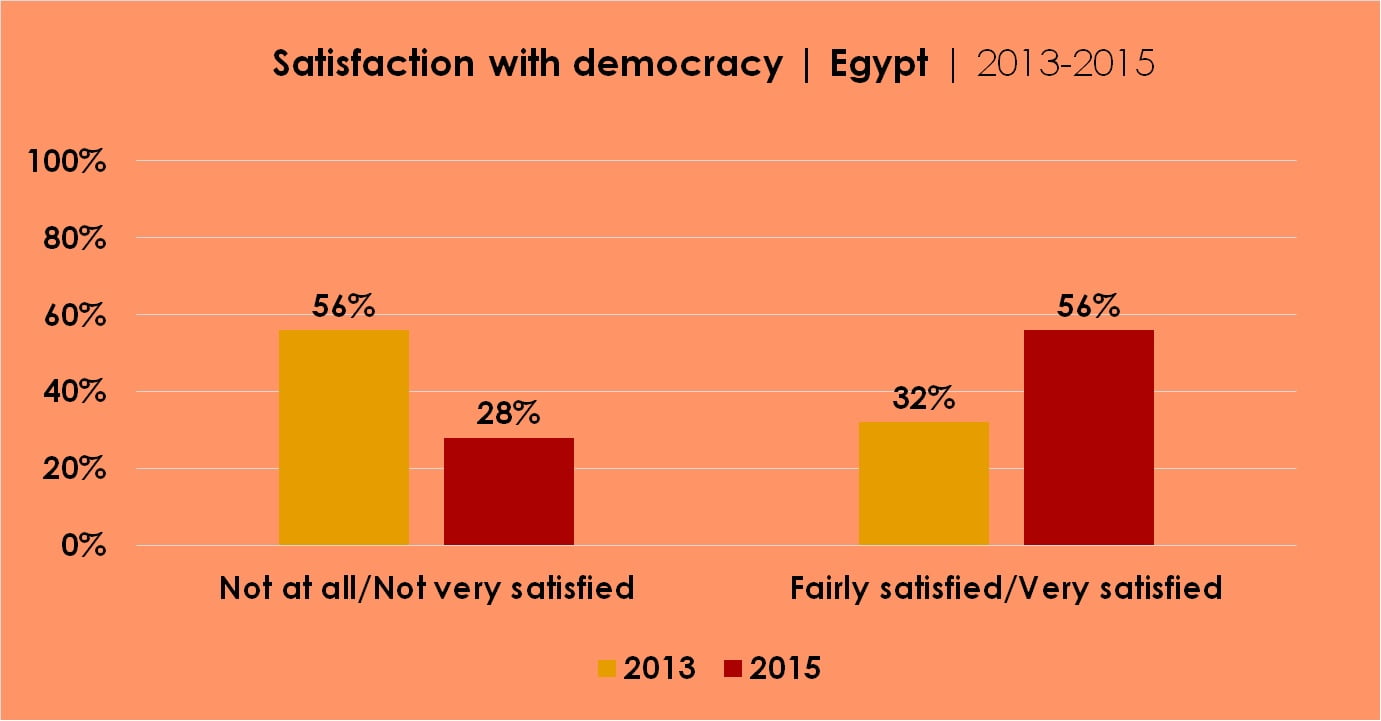

- Similarly, a majority (56%) – almost twice as many as in 2013 – say they are “fairly satisfied” or “very satisfied” with the way democracy is working in their country.

- However, Egypt ranks well below the continental average in its support for democracy (54%) and its rejection of non-democratic regimes such as one-party rule (60%), one-man rule (49%), and especially military rule (33%).

- When Egyptians are asked what the word “democracy” means to them, the most frequent responses are “civil liberties and personal freedoms” and “equality and justice.”

- While majorities say they feel at least “somewhat” free to say what they think (75%), to join any political organisation they want (62%), and to vote as they wish (70%), these proportions have declined since 2013.

In early 2016, five years after the beginning of the Arab Spring, the Economist (2016) reported that hopes raised by the uprisings had been destroyed. “The wells of despair are overflowing,” the newspaper said, the uprisings having brought “nothing but woe.” In addition to stagnant economic growth, rent-seeking was “rampant,” security forces continued to repress the population, and grounds were more fertile than ever for the emergence of radicals “who posit their own brutal vision of Islamic Utopia as the only solution.”

Egypt, considered a bellwether in the region, was included in this bleak picture. Egyptians overthrew the autocratic regime of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 and voted in a staunchly Islamist government headed by Mohamed Morsi of the Freedom and Justice Party. In June 2013, in a “soft coup” riding a wave of popular anger against the Islamist regime, the head of the Egyptian military, Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi, became the latest president of Egypt to tout democratic ambitions for the country.

In a speech in early 2016, al-Sisi, having swapped his military uniform for a suit, told the Egyptian Parliament that the country had made a bold return to democracy and that constitutional institutions had been rebuilt. Many analysts differ, describing the current state as “not just cruel, arbitrary and unaccountable, but also both too incompetent and too broke to buy [the population’s] acquiescence” (Economist, 2015). Rights groups have accused the al-Sisi regime of wide-scale repression, including the jailing of thousands of Islamists and secular activists who took part in the 2011 uprisings against Mubarak (New Arab, 2016). Freedom House (2016) rates Egypt as “not free,” with political-rights and civil-liberties scores of 6 and 5, respectively (7 being the worst possible).

Using Afrobarometer survey data from Rounds 5 and 6, we inquire whether this external perception is shared by Egyptian citizens. How do they perceive their democracy and their government? Afrobarometer data provide a good indication of how Egyptians’ attitudes have evolved in the three years since the country’s first post-Arab Spring elections. Mohamed Morsi ruled from June 2012 to July 2013. The Round 5 survey in Egypt was conducted in March 2013, shortly before the end of Morsi’s rule. Round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey was conducted in June/July 2015 – almost exactly one year into al-Sisi’s presidency.