- More than four in 10 Liberians had a relative or close friend who became infected with (45%) and/or died of (41%) Ebola.

- During the year preceding the survey – the height of the epidemic – three-fourths (77%) of Liberians went without medicine or medical care at least once, an increase of 9 percentage points from the 2012 survey. More than half (52%) say they had to pay bribes to obtain health care.

- The Ebola outbreak disrupted the daily lives of most Liberians, as large majorities could not attend social and communal events (89%), attend school (86%), or engage in income-generating activities (86%).

- In Liberians’ assessments of who was effective in providing care for Ebola victims, treatment facilities of international entities (85%) and local non-governmental organisations (73%) fare better than Liberian public hospitals and clinics (49%), private hospitals and clinics (40%), and traditional medicine practitioners (30%).

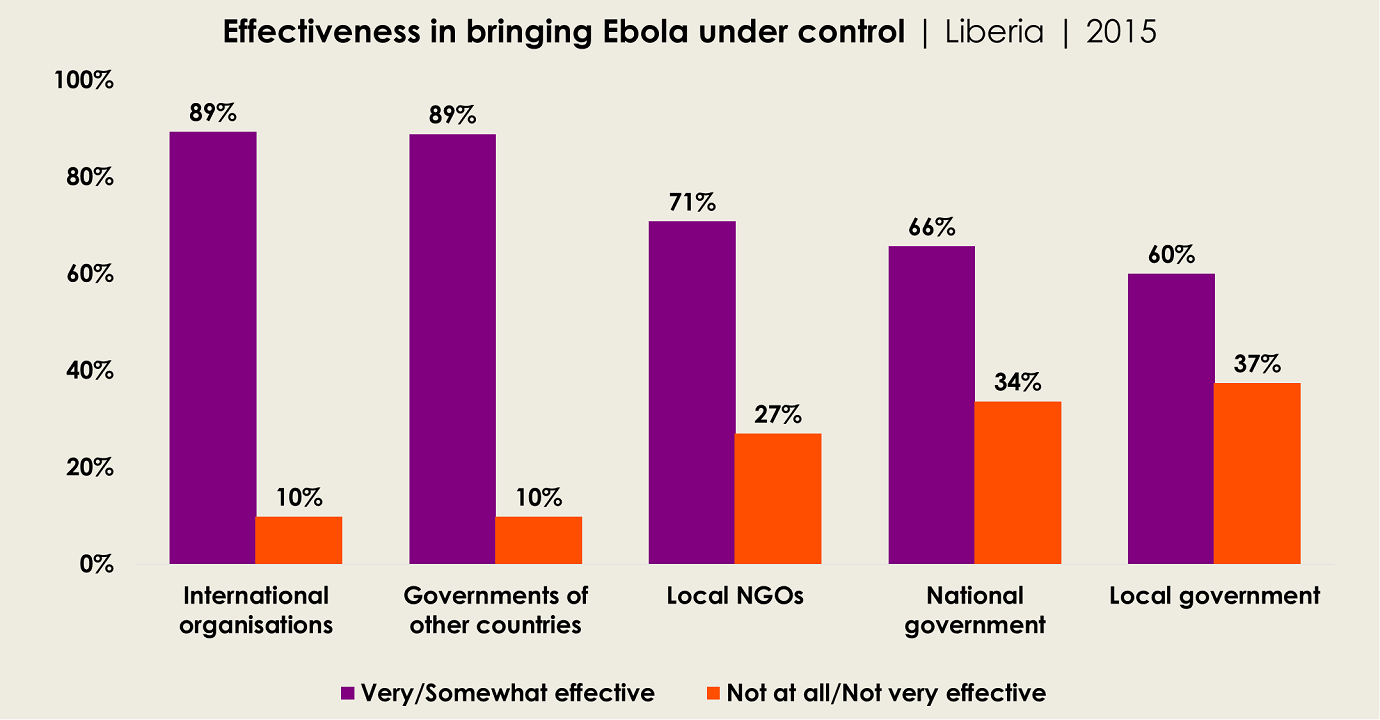

- Similarly, in bringing Ebola under control, international organisations (89%), governments of other countries (89%), and local non-governmental organisations (71%) are widely seen as having been effective.

Liberia is one of five West African countries hit by the world’s worst outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease. Between March 2014 and May 2015, the epidemic in Liberia produced 10,675 suspected, probable, and confirmed infections and killed 4,809 people, including about 200 health-care workers (Doctors Without Borders, 2016).

The outbreak overburdened Liberia’s weak health-care system and affected all aspects of life. The country declared a three-month state of emergency, and the military helped enforce the closure of markets and schools, curfews, restrictions on the movement of patients and their contacts, and the quarantine of some parts of the country (e.g. the West Point slum). International bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO), the U.S. Army and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Germany’s International Search and Rescue (ISAR), and Doctors Without Borders constructed, equipped, and staffed makeshift treatment centers for Ebola patients. In May 2015, the WHO declared Liberia Ebola-free, although a few additional cases led to new “Ebola-free” declarations in September 2015 and January 2016.

Findings of an Afrobarometer survey conducted at the end of the epidemic confirm the pervasive effects of the Ebola outbreak as it disrupted daily activities and exacerbated difficulties in getting non-Ebola medical care. Most Liberians say that foreign assistance was more effective than Liberian institutions in providing care for Ebola patients and bringing the epidemic under control, but they also praise their government’s handling of the crisis and are confident in its preparedness in case of an Ebola outbreak in the future.

Related content