- A majority of South African youth say they are “somewhat” or “very” interested in public affairs (55%) and discuss politics at least “occasionally” (73%). While discussion of politics has increased since 2004 (by 13 percentage points), reported interest has been relatively stable over time.

- At least two-thirds of survey respondents aged 18-35 years believe that citizens should “always” vote in elections (69%), pay taxes (67%), and complain if public services are of poor quality (66%) – all of which are generally associated with good citizenship.

- Three in 10 youth (30%) are active members or official leaders of a religious group, while 15% are actively involved in a voluntary association or community group. Membership in religious groups has declined by 17 percentage points since this question was first asked in 2004.

- Half (51%) of young citizens say they attended a community meeting at least once in the previous year, and one-third (34%) say they joined others to raise an issue. Participation in protest action was less common (15% on average across five types of protest activities).

- Two in 10 youth (19%) say they participated in a demonstration or protest march in 2015, an 8-percentage-point increase since 2011. However, this remains below the levels recorded in 2002-2006.

South Africa’s Youth Day 2016 (16 June) marks the 40th anniversary of the Soweto uprisings, during which thousands of high school students marched to protest the introduction of Afrikaans as a language of instruction in the public education system. The demonstrations proved to be a watershed in the fight against apartheid by bringing South African youth to the forefront of the liberation struggle (South African History Online, 2016). Mattes and Richmond (2015) argue that since then, South Africans have held “contradictory” beliefs about the nature of young people’s role in politics: “On one hand … many people see youth as the primary catalyst of activism and political change. … On the other hand … a wide range of commentators routinely experience ‘moral panic’ about the apparent ‘crisis’ of youth and its corrosive effect on the country’s political culture” (p. 1).

Youth political engagement has again come into focus during ongoing nationwide “fallist” protests led by university students demanding change in South African higher education institutions. In January 2016, the Minister of Higher Education and Training, Dr. Blade Nzimande, met with student representatives to present progress toward eight demands, including addressing financial barriers to higher education, inadequate housing, and exclusionary language policies (Ministry of Higher Education, 2016a). However, the following month his office released a statement condemning damage to university property amidst renewed protests (Ministry of Higher Education, 2016b).

Despite this renewed activism among university students, findings from the 2015 Afrobarometer survey indicate little change in levels of political participation among South African youth (aged 18-35 years) in general. While half of young survey respondents say they attended a community meeting in the previous year, only minorities report engaging in various other forms of civic and protest action, including protest marches. Youth participation in demonstrations is higher than in 2011 but lower than the levels reported in 2000-2006. These results suggest that student activism is atypical of South African youth’s political behaviour in general and that any further youth engagement on issues of transformation in the country is likely to remain concentrated on university campuses.

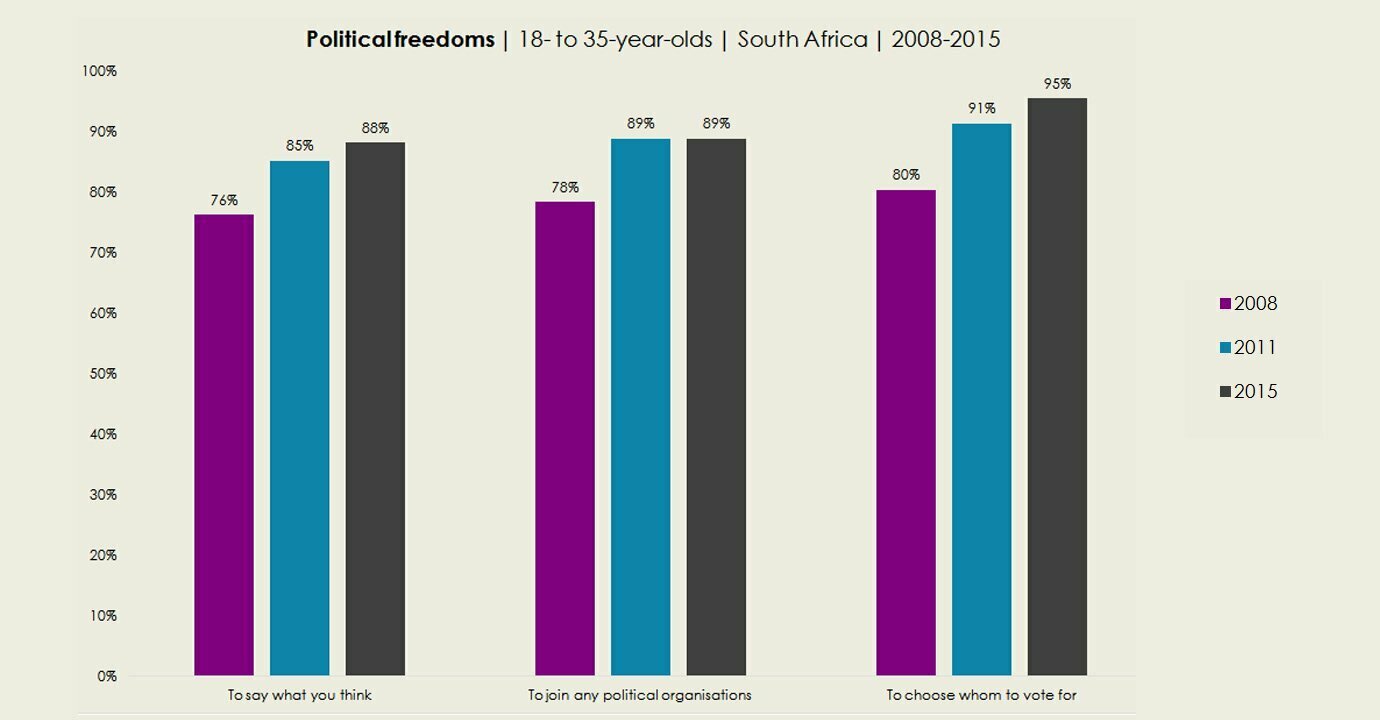

Although perceptions of political freedoms have increased since 2008, ordinary young South Africans appear to see the country’s leadership as relatively inaccessible. However, rising contact levels with local government officials indicate that youth may be increasingly willing to hold their elected leaders accountable at this level of government.

Related content