Originally posted on allAfrica.com.

There has been an explosion in the number of African elections since the “fourth wave” of democratisation began in the early 1990s. In March 2016 alone, Africa will see elections in “advanced” democracies in Benin (presidential), Cape Verde (legislative), and Tanzania (regional) as well as a constitutional referendum in Senegal.

While elections may represent progress, many are considered to be of questionable quality, appearing to be mere “rubber-stamping” exercises intended to legitimise and further entrench incumbents.

Uganda’s elections in February, for example, extended President Yoweri Museveni’s tenure for another five years (he has been in power since 1986) amidst allegations of vote fixing and voter intimidation and a confirmed shutdown of all social media on request of the country’s electoral commission. The African Union Election Observer Mission’s preliminary assessment describes the elections as “largely peaceful” and highlights only procedural deficits, such as the late delivery of materials.

Senegalese President Macky Sall’s initiative to reduce presidential terms – including his own – from seven years to five years is notable, given recent moves in numerous countries to circumvent term limits. Since 2001, Senegalese presidents are restricted to two terms, and public opinion data from the Afrobarometer survey indicates strong support for this limit among ordinary citizens. On 20 March, Senegalese citizens will vote on Sall’s proposed shortening of presidential terms, among other constitutional reforms.

A 2013 analysis of elections in sub-Saharan Africa revealed that although there has been significant growth in the number of democratic turnovers (a peaceful electoral alternation of ruling parties) in the region since 1990, these represented only 23% of electoral results between 1990 and 2012. The number has since grown to include Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zambia, all of which experienced peaceful alternations of power in 2015.

The 2016 election schedule includes polls in seven of Africa’s most well-regarded democracies, which are considered “free” by Freedom House’s influential measure of political rights and civil liberties (see Table 1). These countries not only meet the minimal requirements of electoral democracy (i.e. free and fair multiparty elections), but also guarantee a relatively high level of political freedoms.

Tunisia is the newest entrant and is currently the only country in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) with this status, following a series of political reforms and successful elections in 2014. It remains to be seen whether political actors will be able to sustain this momentum in the long term.

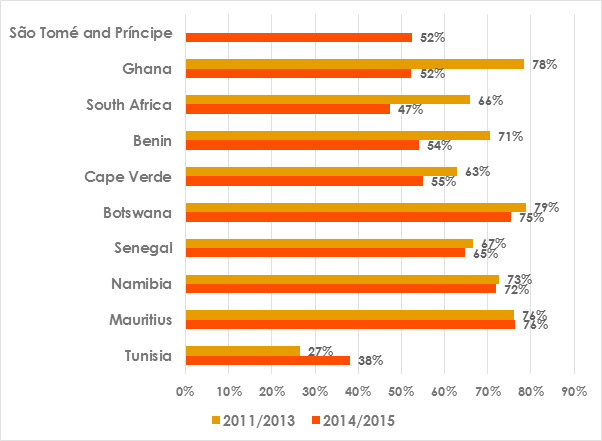

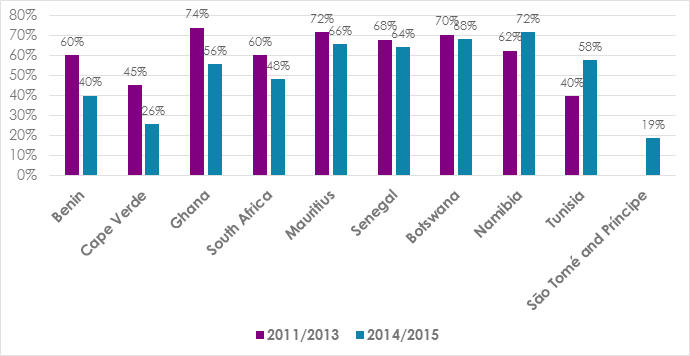

Recent analysis from the latest round of the Afrobarometer survey of the continent’s 11 “free” countries indicates that citizens are becoming increasingly critical of the way their democracies are working, despite high scores on international measures such as Freedom House’s and the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG). Although these populations largely continue to support democracy, citizens are much more critical when asked about how it actually functions in their country. On average, six in 10 (59%) believe that their country is “a full democracy” or one with only “minor” problems, while only half (52%) are at least “fairly satisfied” with its implementation (see Figures 1 and 2).

Ghana, for example, has experienced two peaceful electoral turnovers (2000 and 2008), which would suggest that its democracy is among the most consolidated in Africa. However, between 2012 and 2014, the country experienced the largest decline among surveyed countries in the proportion of citizens who both believe that the country is a democracy and are satisfied with its implementation. This could be related to lingering dissatisfaction with the controversial outcome of the 2012 election: Less than half (46%) of Ghanaians say the poll was “completely free and fair” or “free and fair, with minor problems.” That year, as in each election since 2000, the losing party challenged the results, despite international recognition of their credibility.

South Africa also experienced significant growth in citizen dissatisfaction with democracy, which is at its highest level since 2002, despite great admiration for the country’s success since its 1994 transition.

It is still unclear whether these declines in satisfaction levels reflect deteriorating “objective” measures of democracy (e.g. election quality) or whether citizens are becoming increasingly demanding of how democracy should work.

Cape Verde, for example, is the only African country to receive Freedom House’s best possible score, and has done so since 2003. Furthermore, the country ranks first on the “Participation and Human Rights” measure of the IIAG. Despite these accolades, only 55% of its citizens believe the country is a democracy, and significantly fewer (26%) are satisfied with its implementation. Furthermore, only 56% were satisfied with the last election’s quality (2011), despite international recognition of both polls as “free and fair.”

These results show the difficulty of assessing the quality of any country’s democracy, even the most respected, as citizen views can often contradict expert opinions and “objective” measures. Democratic consolidation requires legitimation of the system’s rules, institutions, and norms by both political actors and ordinary citizens. Despite enjoying a wide range of political freedoms, citizen satisfaction in Africa’s most lauded democracies is well below public support for democracy itself.

Time will tell whether citizens will use the ballot to express this dissatisfaction and whether their leaders will manage to meet voters’ expectations after this year’s electoral cycle.

Table and charts

Table 1: “Free” countries with elections scheduled for 2016

| Country | Election type | Election date |

| Benin | Presidential | 06-Mar |

| Cape Verde | Parliamentary | 20-Mar |

| Presidential | August | |

| Senegal | Constitutional referendum | 20-Mar |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | Presidential | July |

| South Africa | Local/municipal | By August |

| Tunisia | Local/municipal | 30-Oct |

| Regional | ||

| Ghana | Parliamentary | 07-Nov |

| Presidential | 07-Nov | |

| NB: The other “free” countries (with no elections scheduled for 2016) are Botswana, Mauritius, and Namibia. Since publication, Lesotho has been downgraded from “free” to “partly free” and is therefore excluded from this analysis. |

Figure 1: Extent of democracy | 10 “free” countries | 2011-2015

Respondents were asked: In your opinion, how much of a democracy is [country] today: A full democracy? A democracy, but with minor problems? A democracy with major problems? Not a democracy? (% who say “a full democracy” or “a democracy, but with minor problems”)

Figure 2: Satisfaction with democracy | 10 “free” countries | 2011-2015

Respondents were asked: Overall, how satisfied are you with the way democracy works in Botswana? (% who say “very satisfied” or “fairly satisfied”)

Rorisang Lekalake is Afrobarometer's assistant project manager for Southern Africa, based at the Institute for Justice and Reconciliation (IJR) in Cape Town, South Africa.