Most of us were taken by surprise when Mali – a budding democratic success story after three open elections and two peaceful transitions of power – imploded with a separatist insurgency, a military coup, and the breakdown of state control in 2012.

What did we miss? Were there signs of impending instability that political observers overlooked in the pre-crisis period? And if so, can such early-warning indicators help us predict political risks for other African governments and political regimes?

An exploratory analysis suggests that public opinion survey data can be used to measure emerging risks in African political systems by systematically tracking certain dimensions of mass political support, such as approval for incumbent governments and satisfaction with the performance of political regimes. When public disapproval goes up, so does political risk, raising red flags even for once-stable democracies such as Ghana.

Measuring political risk

If political risk is the likelihood that those in power will lose management control, its characteristics can directly affect both governments (meaning the leaders in office) and political regimes (meaning the “rules of the political game,” ranging from democracy to autocracy). Political systems can absorb risk to a particular government; indeed, some alternation of governments is expected in democratic regimes. But risk to a political regime has more far-reaching consequences, especially if it signifies backsliding from democracy toward autocracy.

As a way to measure political risk, Afrobarometer surveys conducted over 15 years in a growing number of African countries offer numerous indicators of public attitudes toward incumbent leaders, democracy, and alternate regimes. Risk to the incumbent government can be measured by the average proportions of survey respondents who disapprove of the job performance of their president, their parliamentary representative, and their local government representative. Risk to the political regime is quantifiable in the average proportions of respondents who are dissatisfied with the way that democracy works in their country and who consider that their country is not a democracy or is a democracy with major problems.

Cross-national comparisons can identify countries with high baseline risk, while sharp and sustained upturns in disapproval over time signal increasing risk.

In retrospect: Mali

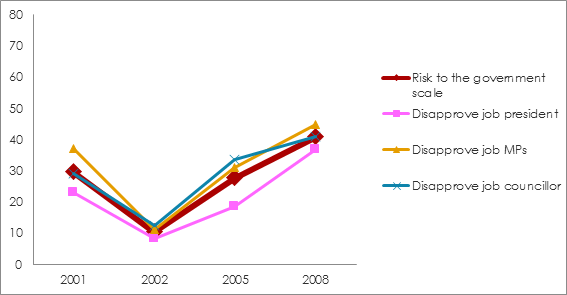

There is evidence of precisely such early warnings well before the 2012 crisis in Mali. Figure 1A, reflecting risk to the government, shows disapproval of the job performance of elected leaders, which jumped by 30 percentage points (to 41%) between 2002 and 2008.

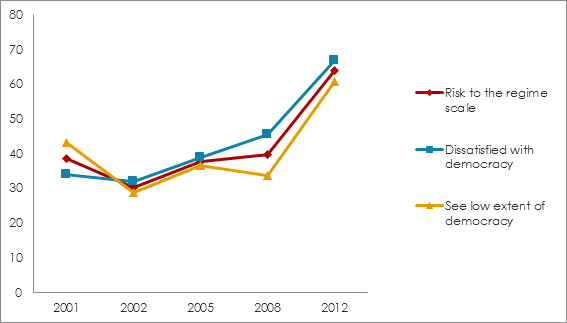

Similarly, Figure 1B traces an upward trend in the scale of risk to the political regime (multiparty democracy). By December 2012, almost two out of three Malians were dissatisfied with democracy (and, not coincidentally, almost half believed that “all” or “most” government officials were “involved in corruption”).

Figure 1A: Mali: Risk to the government | 2001-2014

Figure 1B: Mali: Risk to the regime | 2001-2014

Early warnings for Ghana and beyond?

The Malian experience (and similar evidence from Kenya and Zimbabwe) may offer lessons for other parts of Africa. Ghana, for example, often considered a model for political development on the continent, has seen a drastic increase in public disapproval of the government’s performance that could threaten a 2016 re-election bid by President John Dramani Mahama and raise the spectre of broader risks for Ghana’s regime of democracy.

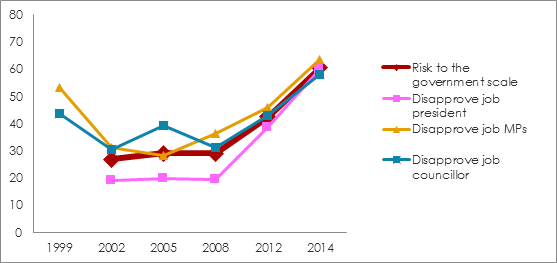

As shown in Figure 2, after years of relative public satisfaction paralleling the country’s strong democratic and economic performance, between 2008 and 2014 Ghana registered increases in all political risk factors in a pattern reminiscent of Mali between 2002 and 2008. Perhaps reflecting swelling budget deficits, frequent electricity blackouts, slowing economic growth, and frequent corruption scandals, risk to the incumbent government stood at an alarming 60% in 2014 – more than double the risk just six years earlier.

Risk to the regime also more than doubled between 2008 and 2014, though at 37% it was still moderate compared to the high risk facing the incumbent government.

Figure 2: Ghana: Risk to the government | 1999-2014

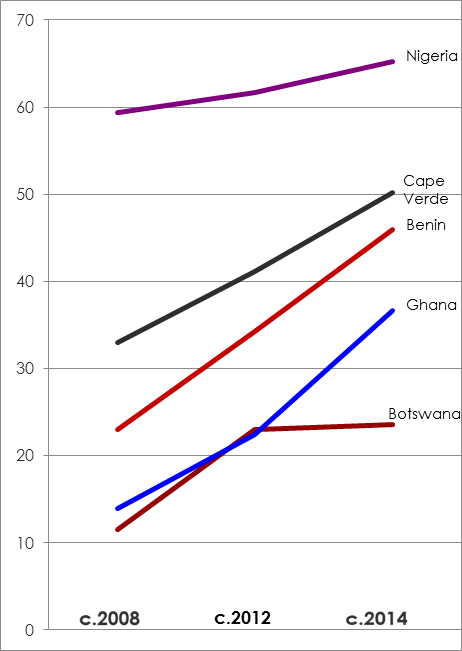

An analysis of 12 countries for which new data are available points to four other countries that in 2014 displayed early-warning signs of political instability. Focusing on risk to the political regime, Figure 3 shows sharp and consistent upward risk trajectories for Nigeria, Cape Verde, Benin, and Botswana, in addition to Ghana.

Given citizens’ tendency to let their perceptions of specific leaders “spill over” into their confidence in democracy, it seems likely that Nigeria’s successful 2015 election will sharply reduce that country’s risk to democracy. Similarly, a solid election and peaceful change in government in 2016 could prove sufficient to offset nascent signs of popular doubts about democracy in Ghana.

Figure 3: Risk to the regime: Five-country comparison | 2008-2014

Developing a risk-analysis tool

Tracking social survey data is a promising approach to predicting political risk, but the development of a high-quality risk-analysis tool will require extensive additional conceptual, empirical, and interpretive work. (For a fuller analysis and discussion, read Working Paper No. 157) While this exploratory analysis calls attention to specific red flags, it is but a first step on the long road to reliable risk identification and, longer still, risk management.

Written by Michael Bratton, E. Gyimah-Boadi, and Brian Howard:

Michael Bratton is University Distinguished Professor of Political Science and African Studies, Michigan State University, and senior adviser to Afrobarometer. Email: mbratton@msu.edu

E. Gyimah-Boadi is executive director of the Center for Democratic Development, Ghana, and executive director of Afrobarometer. Email: gyimah@cddgh.org

Brian Howard is publications manager for Afrobarometer. Email: brianhoward58@gmail.com

A version of this blog post was originally published by The Conversation: Africa