Originally published on the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, where our regular Afrobarometer series explores Africans’ views on democracy, governance, quality of life, and other critical topics.

By Carolyn Logan, E. Gyimah-Boadi, and Joseph Asunka

African citizens are raising their voices. In just the past three months, protesters have taken to the streets to demand democracy in Eswatini and to show their opposition to anti-democratic power grabs in Tunisia and Sudan. Since April 2017, the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has recorded more than 70 episodes in 35 African countries of protests focused on issues ranging from police brutality and presidential third-term attempts to COVID-19 restrictions.

Citizen participation and government responsiveness are cornerstones of democracy. In the first installment in this Afrobarometer series in anticipation of the Biden administration’s Dec. 9-10 Summit for Democracy, we reported that African citizens are committed to democracy — even if they aren’t getting as much of it as they want. In this final installment, we focus on citizen voice: How, and how much, do citizens express their preferences, evaluations, and aspirations? And are their governments listening?

These findings draw on 45,832 face-to-face interviews in 34 countries during Afrobarometer Round 7 (2016 to 2018), which included a special set of questions on these topics. The data reveal that Africans invest considerable effort in making themselves heard. But their governments are not always listening or responding. In fact, sometimes governments suppress citizen action. Yet the findings suggest that a more responsive approach could yield greater participation and greater political satisfaction.

Africans are not keeping quiet

Voting is the most obvious and popular way for citizens to express themselves, and Africans take advantage of this opportunity: 67% of respondents said they voted in their most recent national election.

But votes are blunt instruments for expressing preferences and complaints. Elections occur only occasionally, and they force individuals to compress a wide array of views into very few choices. How do Africans find their voice during the long intervals between elections?

Many invest in personal efforts to act as agents of change, whether in fighting corruption in the management of natural resources in Ghana or initiating awareness-raising and relief campaigns in response to COVID-19 in Cameroon, Kenya, South Africa, and South Sudan.

Afrobarometer findings reveal substantial citizen engagement. Nearly half of survey participants (48%) say they “joined with others to raise an issue” at least once in the past year, and 34% contacted a political leader “about some important problem or to give them [their] views.”

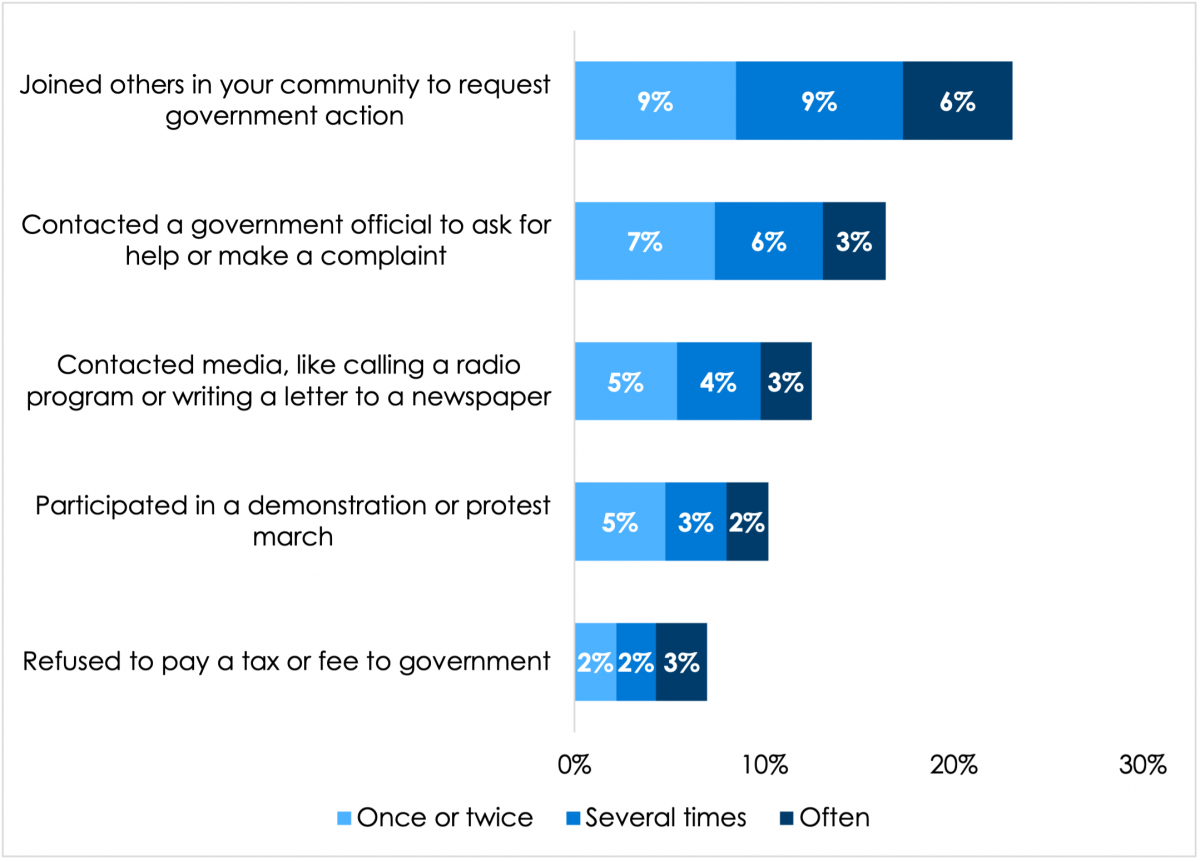

Citizens also report taking direct action when they are dissatisfied with government performance, as shown in Figure 1. Nearly one in four (23%) report they “joined with others to request government action” over the past year, while 16% lodged a request for help or a complaint with a government official, 13% contacted the media, and 10% participated in a demonstration. Seven% said they refused to pay taxes or fees to the government.

Figure 1: How citizens respond when dissatisfied with government performance | 34 African countries

But are governments listening?

These robust levels of citizen engagement suggest that people feel they can make a difference. But decision makers aren’t always receptive or responsive to citizen voices. Only 22% of survey respondents think local government councillors “often” or “always” listen “to what people like you have to say,” compared to 38% who say these elected officials never do. The comparable percentages for members of parliament (MPs) are even worse (16 and 47%, respectively). Even in some of the continent’s most highly rated democracies, most citizens don’t feel heard: Just 12% in Cabo Verde and Mauritius, and 11% in Namibia, think their local elected leaders are listening.

Public officials who don’t understand or who disregard the accountability relationship between citizens and their government are also likely to prove unresponsive to the people’s concerns. For example, while a majority (57%) of survey respondents say they would probably get a response if they reported a problem such as teacher absenteeism at their local school, 36% think they would not. And fewer than half (43%) believe officials would take action if they reported corrupt behavior.

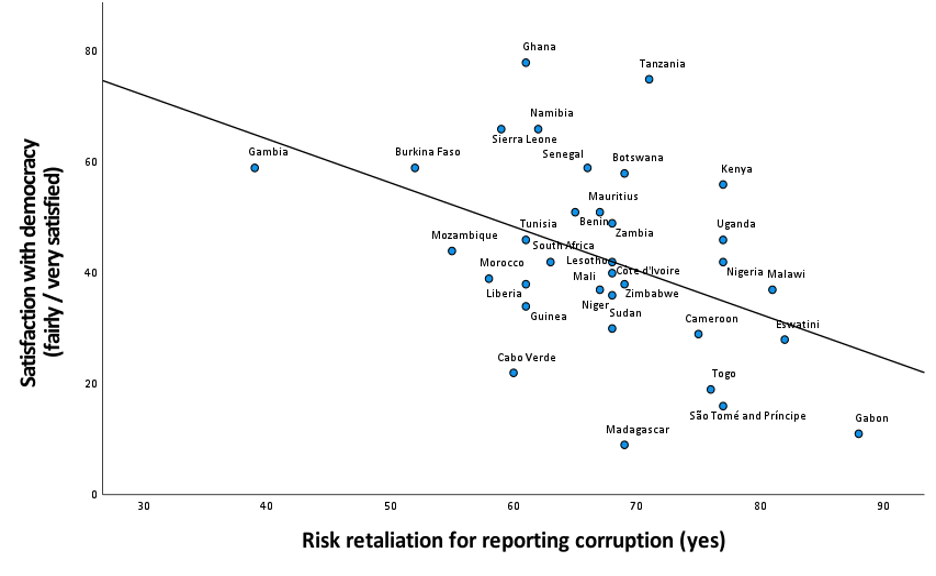

In fact, fully two-thirds (67%) say people “risk retaliation or other negative consequences” if they report incidents of corruption; just 29% think they can make such a report without fear. As shown in Figure 2, majorities in 33 of 34 surveyed countries believe they would face retaliation, including more than eight in 10 citizens in Gabon (88%), Eswatini (82%), and Malawi (81%).

Figure 2: Do citizens believe they can safely report corruption? | 34 African countries

The implications of (not) listening

Lack of government responsiveness and respect for popular voices may have direct implications for both citizen engagement and citizen satisfaction.

For example, we find that individuals are more likely to contact leaders or take other individual or collective actions to solve problems if they believe a) that government officials respect and listen to them, b) that they will get a response if they raise an issue, and c) that they do not need to fear retaliation. In our findings, almost all of these interactions show modest but statistically significant positive correlations.

There is also evidence that responsive governance is linked to greater citizen optimism and satisfaction. When we compare country averages for government responsiveness to key democracy indicators such as the percentage who are satisfied with democracy or positive about the direction of the country, we again find positive associations. Countries where more citizens report that government officials treat them with respect and that MPs listen to their constituents also tend to report a stronger sense that the country is going in the right direction. Similarly, as shown in Figure 3, countries where fewer people believe they risk retaliation for reporting corruption tend to report greater satisfaction with democracy. The same is true of countries where local government councillors listen.

Figure 3: Correlation between satisfaction with democracy and risk of retaliation for reporting corruption | 34 African countries

When governments are responsive, citizens are more likely to engage in addressing community needs, and to be satisfied with their political system and optimistic about the future. Respectful and responsive governance has the potential to spur citizen action that can contribute to solving critical development challenges.

Related content