Originally published on the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, where our regular Afrobarometer series explores Africans’ views on democracy, governance, quality of life, and other critical topics.

Police forces across much of Africa are coming under increasing scrutiny, facing such challenges as complaints of overly aggressive enforcement of COVID-19 restrictions and the #EndSARS protests against police brutality that rocked Nigeria in 2020. A recent study in Kenya found that the number of misconduct cases filed annually against police officers has grown sixfold over the past decade. Recent police abuses in Nigeria, South Africa, and elsewhere have drawn widespread condemnation, although accountability is still lacking.

Afrobarometer’s 48,084 face-to-face interviews in 34 African countries from 2019 to 2021 – Round 8 of our periodic surveys – found widespread skepticism of police motives and actions. The poorest and most vulnerable – those who are most likely to be victimized by crime –are also most likely to report being preyed upon by the police.

Protectors or predators?

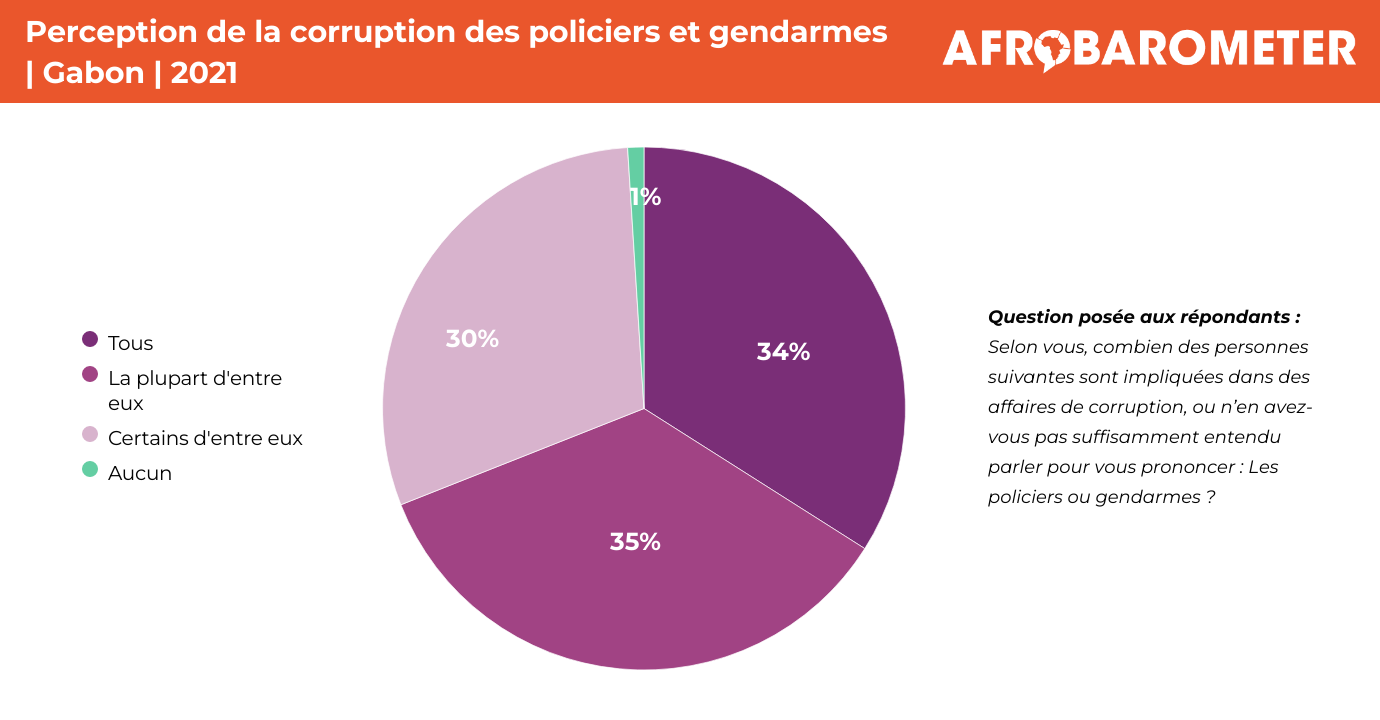

Afrobarometer’s latest findings continue to show that Africans see the police as the most corrupt among key state institutions. Nearly half (47%) of respondents saw “most” or “all” police as being involved in corruption, a larger proportion than for parliamentarians (38%), civil servants (36%), officials in the presidency (35%), court officials (35%), and tax officials (35%).

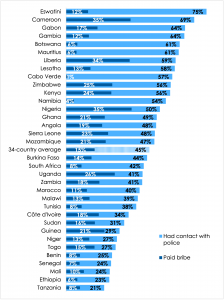

What does this mean in the lives of ordinary citizens? Our data show that in many countries, citizen encounters with police are quite common. Fifteen percent of all respondents across 34 countries said they had sought out police assistance within the past year; 39% had encountered the police in some other (usually involuntary) circumstance, such as at a roadblock or identity check or during an investigation. In total, almost half (45%) of all citizens reported having had direct contact with police in the past year. Considering that many citizens see the police as more predatory than protective, this is a high threat level.

The frequency of police-citizen interaction varies widely across 34 countries. As shown in the figure below, one-fourth or fewer citizens had contact with the police in Tanzania (21%), Ethiopia (23%), Mali (24%), Senegal (24%), and Benin (25%). But in Eswatini a remarkable three out of every four citizens (75%) interacted with police, and nearly as many did so in Cameroon (69%).

Contact with the police and payment of bribes | 34 countries | 2019/2021

Figure shows the%ages of all respondents 1) who had contact with police during the previous year (light-blue bar) and 2) who reported having paid a bribe (dark-blue bar).

The helpful or predatory nature of these interactions also varied markedly, even among countries with similar levels of contact with police. In Eswatini, 12% of all respondents said they wound up paying a bribe, or about one in every six who had contact with the police. In Cameroon, with a similarly high contact rate, 35% of all respondents paid a bribe – fully half of those who interacted with the police. In Nigeria, while the overall contact rate was somewhat lower at 50%, a remarkable seven in 10 of those who had contact (35% of all Nigerians) paid a bribe at least once, confirming the reputation of Nigeria’s police as among the most crooked on the continent.

The poor, crime, and fear

In earlier survey rounds, Afrobarometer learned that the poor are much more likely to be victims of crime than the rich. Across 34 countries surveyed in Round 7 (2016-2018), the poorest respondents were twice as likely as the wealthiest (37% vs. 19%) to report having suffered a theft from their home in the past year, and they were nearly three times as likely to report having been physically attacked (14% vs. 5%).

Similarly, our latest data show that the poorest citizens experience fear much more often than the wealthy: More than three times as many reported feeling nearly constant fear (“many times” or “always”) while walking in their neighborhoods (28% among the poor vs. 8% among the wealthy) and even within their own homes (22% vs. 6%).

The poor and the police

In societies with inadequate security, the rich have the option to hire private security. The poor have no one but themselves and the police. Our evidence suggests that in some places, the police capitalize on this dependence.

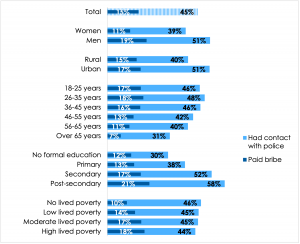

As shown in the figure below, demographic groups differ both in how often they interact with the police and how often they are victimized as a result of that contact. Young, urban, educated men are the most likely to have contact with the police. The wealthy have slightly more contact with the police than the poor, 46% vs. 44%.

Contact with the police and payment of bribes | by socio-demographic group | 34 countries | 2019/2021

Figure shows the%ages of all respondents 1) who had contact with police during the previous year (light-blue bar) and 2) who reported having paid a bribe (dark-blue bar).

But while more contact is associated with more frequently paying bribes for other demographic categories, the pattern is reversed for different income levels. The wealthiest group had the highest contact but the lowest incidence of bribery (10%). Among the poorest, the bribery rate was twice as high (18%) – meaning that more than 40% of poor people who encountered the police wound up paying a bribe. As other research has also shown, the poor are clearly more vulnerable than the wealthy to police predations.

As shown in the figure below, there are three countries – Ghana, Lesotho, and Namibia – where the wealthy are significantly more likely to pay a bribe. But in 18 of 34 countries, the poor are substantially more likely to pay, with the gap reaching 21 percentage points in Nigeria, 14 points in Sierra Leone, and 12 points in Zimbabwe.

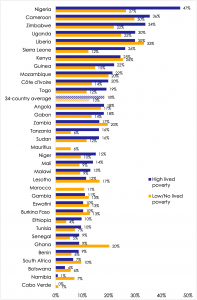

Paid bribes to the police during the past year: Wealthiest vs. poorest citizens | 34 countries | 2019/2021

Figure shows the%age of all respondents in the “high lived poverty” and “low or no lived poverty” categories (regardless of whether they had contact with the police) who reported paying a bribe to police during the previous year. (Mauritius and Morocco “high lived poverty” category is not shown due to small sample size.)

Crime has a disproportionate impact on the poorest and most vulnerable. They are more likely to be victims, and the impact of crime on their lives and livelihoods can be more severe for people who lack resources and safety nets. Yet past Afrobarometer findings have revealed that among those who identified themselves as victims of a crime within the previous year, more than half (56%) never reported it to the police. The most commonly cited reasons for non-reporting have to do with police failures to perform and police untrustworthiness.

While making life better for all citizens, building integrity in Africa’s police forces could also be a valuable step in addressing social inequality.