Blog post by Jamy Felton

The banning of The World newspaper on 19 October 1977 was a pivotal moment in South Africa’s history and brought the fight for media freedom to the fore during apartheid. Today, as we observe South Africa’s Press Freedom Day 2015 (19 October), worries about censorship by the state and politicians are still salient. The South African Bill of Rights (in the 1996 Constitution) declares that “everyone has the right to freedom of expression, which includes (a) freedom of the press or media” with the exception of media that propagates warfare, incites violence,or advocates hate speech (SA Bill of Rights Chapter 2).

While the bill seems to guarantee freedom of the press, according to Freedom House, South Africa’s press freedom was rated “partially free” and ranked 71st in the world in 2014, with a score that declined from 33 to 37 (zero represents absolute freedom). Freedom House cites the “increased use of the National Key Points Act in preventing investigative journalism” of specific institutions and the harassment and killing of journalists as important features leading to this decline. In addition, South African press freedom has gained attention with the debate surrounding the Protection of State Information Bill (POSIB). The main concern about the bill lies in the power granted to government officials to withhold information from the public, thus posing a potential threat to investigative journalism that seeks to expose corruption and injustice.

The Bill of Rights seems to indicate some boundariesto what news media ought to report, and the debate around the POSIB has raised some interesting points about the role the media plays in holding government accountable and exposing corruption. Do South Africans agree on the role the media ought to play in society?

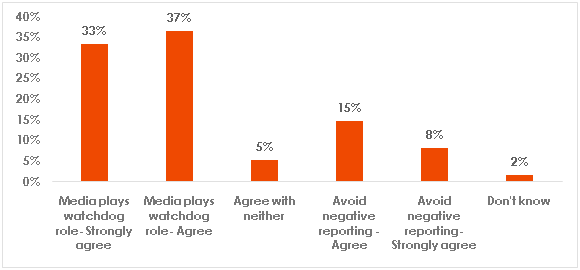

Afrobarometer survey data from 2011 (new survey results for 2015 will be released soon) showed that among South Africans surveyed, 70% agreed or strongly agreed that the media should play its“watchdog” role by constantly investigating and reporting on government mistakes and corruption (Figure 1). What this shows is a strong desire from South Africans for the media to hold government accountable for its actions.

Figure 1: Support for the media’s watchdog role | South Africa | 2011

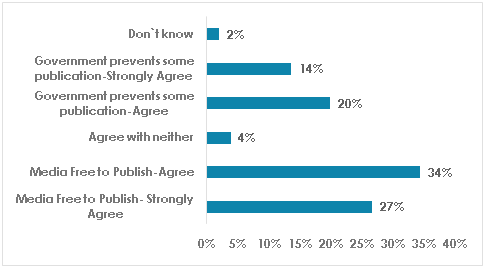

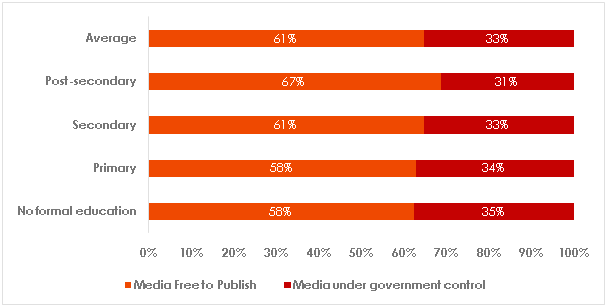

There is also an indication that South Africans believe the media should be free to play this role without interference. More than six in 10 (61%) South Africans agreed or agreed strongly with the statement that “the media should have the right to publish any views and ideas without government control” (Figure 2). This tells us that the POSIB and National Key Points Act should raise concerns ina society that seems to value media independence and freedom. Interestingly, we also see that education seems to have an impact on perceptions of media freedom, with higher levels of education being associated with stronger support for media freedom (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Media’s right to publish vs. control by the state | South Africa | 2011

Figure 3: Media’s right to publish vs. control by the state | by education level | South Africa | 2011

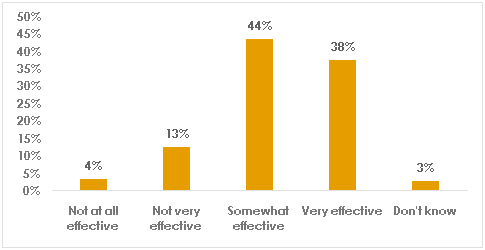

A majority of South Africans believe that the media should have the freedom to do their job. However, do they believe that this translates into practice? According to Afrobarometer data, 81% of South Africans felt that the news media was “somewhat effective” or “very effective” at revealing government mistakes and corruption (Figure 4). This shows a high belief in the efficacy of the media as a government accountability mechanism.

Figure 4: Media’s effectiveness at holding government accountable | South Africa | 2011

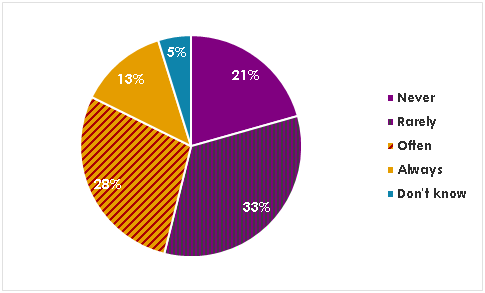

Even though there seems to be an understanding that media freedom is necessary, the Bill of Rights also sets the limitations of media freedom so that it does not amount to abuse. According to the data, there seems to be a fine line dividing those who think the media abuse their freedom and those who think they do not. The data indicate that whilst 33% of respondents felt that the media rarely abused their freedom, 28% felt that they often abused their freedom. In total only 54% of respondents said that the media never or rarely abused their freedom (Figure 5). Perhaps this may be an indication that although there is a demand for media freedom, South Africans also believe that there ought to be some level of respect for the boundaries of what amounts to responsible reporting.

Figure 5: Media’s abuse of its freedom | South Africa | 2011

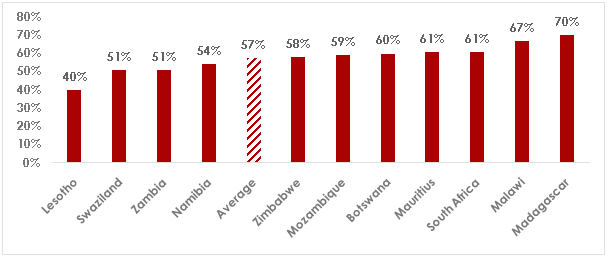

South Africans seem to be strong supporters of media freedom. How do they compare to the rest of southern Africa? In 2011-2013Afrobarometer surveys, data were collected from Botswana, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. According to the data, on average, 57% of southern Africans believed that the media should be free to publish any views and ideas (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Support forthe media’s rightto publish | 11 countries in southern Africa | 2011-2013

This indicates that South Africa is slightly above average in southern Africa. Basotho were the least likely to agree with newspapers being free to publish anything, at 40%. In fact, amajority of Basotho (57%) believed that government should have the ability to prevent newspapers from publishing harmful material. At the other end of the spectrum, 70% of Malagasy said that they believe newspapers should be free to publish their views without interference.

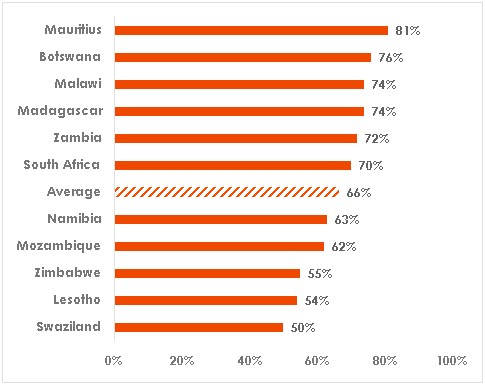

Similarly, 74% of Malagasy felt that the media should have the ability to check government. However, this is not the highest percentage of respondents within a country, with 81% of Mauritians indicating that they believe the media should be a watchdog on government. On average, 66% of southern Africans felt that the media should play this role in society (Figure 7) – a notably higher percentage than those who believed the media should have the freedom to publish what they want. South Africans were once again slightly above the average.

Figure 7: Support for the media’s watchdog role | 11 countries in southern Africa | 2011-2013

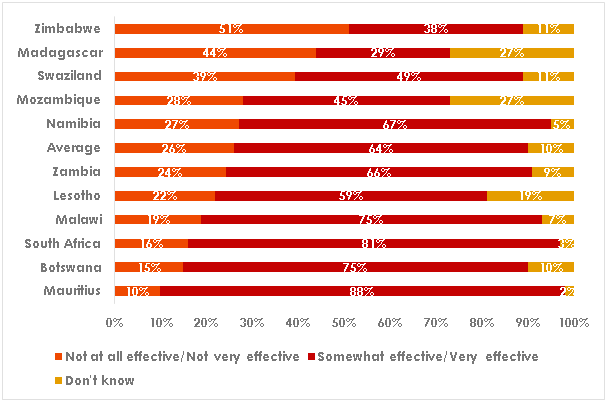

In southern Africa, on average 64% of respondents felt that the media was “somewhat” or “very” effective in playing this watchdog role. Mauritians (88%) felt that their media was doing a good job at playing the watchdog role, whilst South Africans had the second-highest percentage of respondents believing that the media was playing a good role at checking government (Figure 8). On the other hand, more than half of Zimbabweans (51%) felt that the media was not very effective at revealing government mistakes or corruption.

Figure 8: Media effectiveness at holding government accountable | 11 countries in southern Africa | 2011-2013

What does this mean for media freedom in southern Africa, and more specifically in South Africa? It is evident that there is a demand for media freedom across southern Africa, and for the most part,southern Africans are under the impression that the media is doing a good job at fulfilling what people perceive their job to be. South Africans have a slightly-above-average perception of and demand for media freedom. This is good news for democracy in two ways, as the data demonstrate a desire for accountability from government through checks by the media and a demand for freedom of speech.

Of further interest: Is media playing its role in regional integration?

Jamy Felton is the Afrobarometer data quality officer, based at the Democracy in Africa Research Unit in the Centre for Social Science Research at the University of Cape Town, South Africa.