Originally published in GovernanceLink, the African Union’s African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM) newsletter.

Many African leaders have taken decisive steps to limit the effects of COVID-19 in their countries. They have also made a compelling case for why anything short of an ubuntu response – a truly global operationalization of the mantra that “we’re all in this together” – would not only be unethical but would also be doomed to failure (Ahmed 2020; Oladokun 2020).

It’s too early to know what COVID-19 will ultimately mean for Africa and the rest of the world. But it’s not too soon to collect insights, reminders, and warnings that the pandemic affords us, both to guide our response to the current crisis and to be better prepared for the next one.

Three preliminary “lessons” draw on the realities and views of ordinary Africans:

- Long-standing vulnerabilities are being magnified by the pandemic.

- Freedoms often taken for granted are being stress-tested by the pandemic.

- Listening and trust are essential but often scarce resources.

Long-standing vulnerabilities

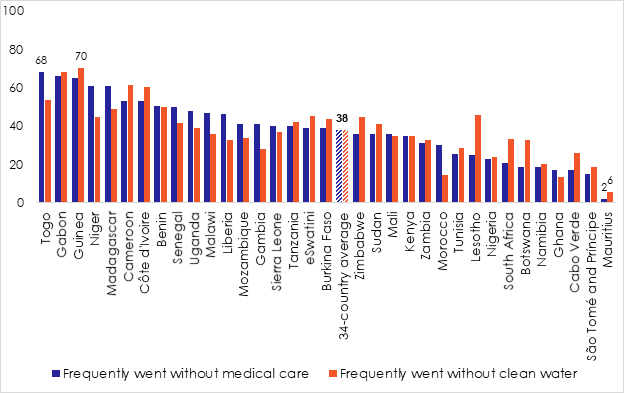

Data collected from more than 45,800 survey respondents across 34 African countries during Afrobarometer Round 7 (2016/2018) highlights some of the vulnerabilities that Africans face as they confront the coronavirus. Hundreds of millions do not have access to clean water, making frequent handwashing and cleaning – a major prevention tool for COVID-19 – all but impossible. Almost four of every ten Africans (38%) went without clean water multiple times in the year preceding the survey, and more than one in five (22%) lack clean water frequently (Howard and Han 2020) (Figure 1).

Just as many (38%) report that they or someone in their family went without needed medical care in the previous 12 months; almost one in five (18%) did so frequently (Howard 2020).

Figure 1: Frequently going without medical care and clean water (%) | 34 African countries | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: Over the past year, how often, if ever, have you or anyone in your family: Gone without enough clean water for home use? Gone without medicines or medical treatment? (% who say “several times,” “many times,” or “always”)

Many African families also lack the economic resilience needed to weather a lockdown (Harrisberg 2020). Two-thirds (66%) of households report going without a cash income several/many times or always during the past year (Mattes 2020). Fewer than one-third say government efforts to improve living standards for the poor (31%) and ensure food security (32%) are effective (Bratton, Seekings, and Armah-Attoh, 2019).

Stress test for rights and freedoms

The pandemic presents risks that extend beyond the necessities of daily life. As African governments implement temporary restrictions that are necessary to protect their citizens from the coronavirus, concerns are also growing that unscrupulous regimes may take advantage of the crisis to roll back rights and freedoms on a more permanent basis. At a time when governments may have to postpone elections and ban public protests to avoid spreading the virus, reports are emerging of leaders using otherwise legitimate lockdowns to strengthen their hold on power (Allison 2020).

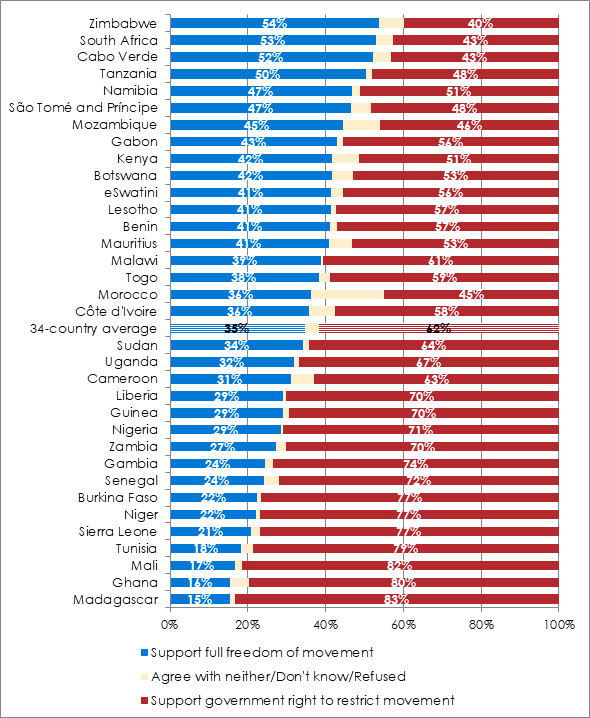

Fearing COVID-19, citizens may accept restrictions they would resist in ordinary times. When Afrobarometer asked respondents in 2016/2018 about their willingness to tolerate government-imposed limits on freedom of movement when public security is threatened, majorities said they would accept such a trade-off (Logan and Penar 2019) (Figure 2). As the pandemic progresses, citizens’ willingness to tolerate restrictions may well be tested. It is unclear whether the public will accept repression if harsh measures prove unsuccessful in protecting them from the virus’ health and economic effects. At the same time, opportunities for the people to voice grievances may be constrained.

Thus, while rapid international support is badly needed to respond to the pandemic in Africa, it is especially important during this crisis that development partners also insist that restrictions be time-limited and transparent, that media freedoms be assured, and that elections be protected or rescheduled in a timely way (UN Human Rights 2020; Freedom House 2020).

Figure 2: Support freedom of movement vs. government right to limit movement to protect security | 34 African countries | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: Even if faced with threats to public security, people should be free to move about the country at any time of day or night.

Statement 2: When faced with threats to public security, the government should be able to impose curfews and set up special roadblocks to prevent people from moving around.

(% who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with each statement)

Listening and trust

Civic activists have been urging African governments to avoid inflexible, one-size-fits-all lockdown decrees. Governments must instead engage local communities in shaping adaptive, context-sensitive measures that accommodate the uniquely difficult circumstances many African communities face (De Waal 2020].

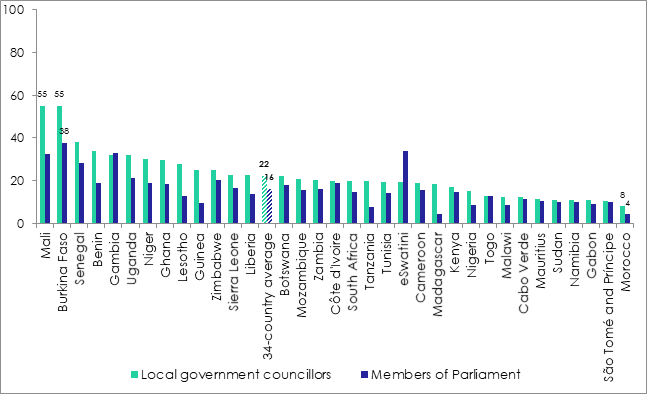

But developing effective local responses will require leaders to listen – not typically regarded as a strength of most governments in the region. Barely one in five Africans (22%) say that members of their local assembly try “often” or “always” to listen to ordinary people, and even fewer (16%) think national leaders such as members of Parliament do so. In only two of the 34 surveyed countries – Burkina Faso and Mali – do majorities (55% each) think that local leaders listen to them. In Morocco, not even one in ten (8%) agrees (Figure 3). Achieving the necessary collaboration will require that leaders unaccustomed to listening to citizen voices urgently commit themselves to more open and effective engagement.

Figure 3: Do leaders listen to people like you? (%) | 34 African countries | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: How much of the time do you think the following try their best to listen to what people like you have to say? (% who say “often” or “always”)

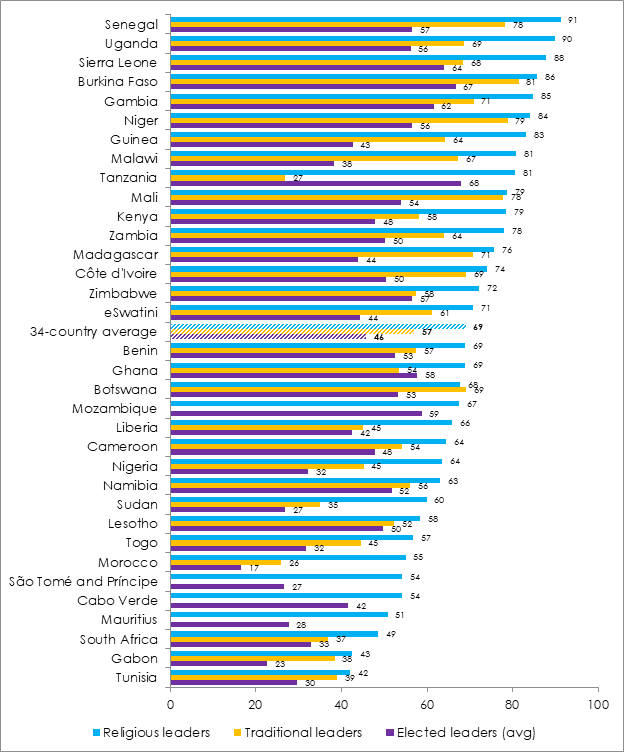

Governments may also face challenges in communicating their coronavirus messages to wary publics. Recent research in Guinea (Grossman 2020) confirms earlier findings from the 2014-16 West African Ebola epidemic (Jerving 2014) that trust in the messenger is critical, especially when it comes to transmitting health messages and inspiring citizens to participate in the response. In many communities, this means that neither national nor international leaders are the ideal conduits. In fact, many of Africa’s elected leaders face a trust deficit. Fewer than half (46%) of citizens trust their elected leaders, when we average trust in the president (52%), Parliament (43%), and local government council (43%) (Figure 4). But governments can and should call on other, more trusted leaders to boost their communication efforts. More than two-thirds (69%) of Africans trust their religious leaders, and a majority (57%) also trust traditional authorities. Engaging these leaders in campaigns to communicate with the public about their role in responding to the crisis may generate critical buy-in.

Figure 4: Trust in elected, traditional, and religious leaders (%) | 34 African countries* | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? (% who says “somewhat” or “a lot.” *Note: The question about traditional leaders was not asked in Cabo Verde, Mauritius, Mozambique, and São Tomé and Príncipe.)

Learning lessons, early and often

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is still in its relatively early stages in Africa, it is not too soon to learn from initial national and global responses, and to adapt where appropriate. Doing so could improve outcomes in ways that save lives and secure livelihoods while also better protecting Africans’ rights and freedoms. We have already witnessed the folly of trying to enforce social distancing by decree in vulnerable communities that have neither the space nor the household resources to make this approach viable. African governments must instead expand channels of communication, listen more to their people, and be significantly more responsive to their needs. Evidence suggests that they will be more effective if they also collaborate with leaders from outside of government who enjoy citizens’ trust, especially religious and traditional leaders.

Even governments with poor records of responsiveness and communication with their citizens would do well to recognize that their response to the COVID-19 pandemic can be an opportunity to re-boot. Engaging with citizens in open and receptive exchanges will not only critically strengthen their response to the current crisis, but also leave them better prepared to face the next one. Likewise, as the international community provides support to backstop these efforts, it should seek to do so in ways that foster and facilitate stronger relationships between African governments and their most vulnerable citizens.

Carolyn Logan is director of analysis for Afrobarometer. clogan@afrobarometer.org. Twitter: @carolynjlogan.

Brian Howard is head of publications for Afrobarometer. bhoward@afrobarometer.org. Twitter: @twitbh1.

E. Gyimah-Boadi is board chairman and interim CEO of Afrobarometer. gyimah@afrobarometer.org. Twitter: @gyimahboadi