Originally published on the Monkey Cage blog.

In Mali, after weeks of large-scale demonstrations demanding that President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta resign, the military settled the matter. Amid international condemnation of last week’s coup deposing Keïta, thousands of Malians celebrated in the streets.

With a military junta running the country, are Malians ready to give up on democracy? Here’s what Malians themselves have to say, based on a recent Afrobarometer survey.

The March-April 2020 survey revealed textbook conditions for a popular uprising as well as strong popular trust in the military — factors that may explain why many Malians seem to welcome, or at least accept, a coup as the country’s best chance to escape a downward spiral of corruption, poor services, and economic failure.

But this year’s nationally representative survey of 1,200 adults also found strong support for democracy and rejection of military rule, suggesting that Malians will try to hold coup leaders to their promise to call elections and transition back to civilian government within a “reasonable” period.

Deep dissatisfaction

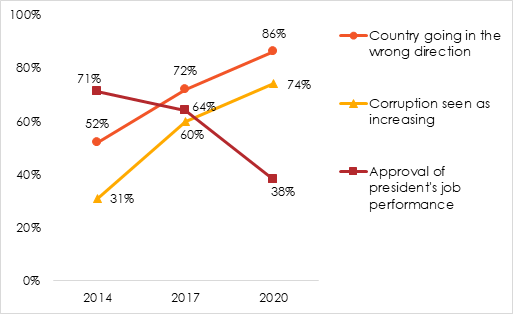

Amid economic conditions that 81 percent of Malians described as bad, survey respondents were clear in their views that the country was off track, that corruption was growing and that their elected officials weren’t up to the job. Compared to two other recent Afrobarometer surveys in the country, Malians’ dissatisfaction has only grown deeper on these measures.

Figure 1: Views on country’s overall direction, corruption, and president’s performance | Mali | 2020

Respondents were asked:

Would you say that the country is going in the wrong direction or going in the right direction?

In your opinion, over the past year, has the level of corruption in this country increased, decreased, or stayed the same? (% who said “increased somewhat” or “increased a lot”)

Do you approve or disapprove of the way that the following people have performed their jobs over the past 12 months, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say: The president? (% who “approved” or “strongly approved”)

Almost 9 out of 10 survey respondents (86 percent) in 2020 thought that the country was going in “the wrong direction.” Even among supporters of the ruling coalition, 82 percent agreed with this statement.

Three-fourths of citizens said corruption increased during the year preceding the most recent survey, including 62 percent who said it increased “a lot.”

Approval of the president’s job performance was at its lowest level (38 percent) since Afrobarometer started surveys in Mali in 2001. Citizens thought even less of their representatives in the National Assembly, whose approval rating stood at only 29 percent.

Malians have a high regard for the military

At the same time, the military is one of the most trusted public institutions in Mali. More than 8 out of 10 citizens said they trust the military, including 62 percent who trust it “a lot.” Even among opposition supporters (78 percent) and in regions battered by a jihadist insurgency since 2012 trust in the armed forces was high — 69 percent of respondents in Gao and 64 percent in Mopti said they trust the military. Far fewer trusted the president (47 percent), legislators (37 percent), the ruling coalition (38 percent) or opposition political parties (36 percent).

Figure 2: Trust in institutions and leaders | Mali | 2020

Respondents were asked: How much do you trust each of the following, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? (% who said “somewhat” or “a lot”)

Most Malians see the armed forces as effective; 80 percent of those interviewed in Afrobarometer’s nationally representative survey of 1,200 adults in 2017 said the military “often” or “always” protects the country from internal and external security threats. In the same survey, 69 percent of Malians agreed with a statement that the armed forces act with professionalism and respect for citizens’ rights.

Demand for democracy

But Malians also soundly reject military rule — 69 percent opposed vs 26 percent in favor in the 2020 survey — and express strong support for democracy. Almost two-thirds said they prefer democracy over any other political system, and even larger majorities disapproved of one-party rule (76 percent) and presidential dictatorship (87 percent).

Figure 3: Support for democracy | Mali | 2020

Respondents were asked:

Which of these three statements is closest to your own opinion?

Statement 1: Democracy is preferable to any other kind of government.

Statement 2: In some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable.

Statement 3: For someone like me, it doesn’t matter what kind of government we have.

(% who “agreed” or “agreed very strongly” with Statement 1)

There are many ways to govern a country. Would you disapprove or approve of the following alternative: The army comes in to govern the country? (% who “disapproved” or “strongly disapproved”)

Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: We should choose our leaders in this country through regular, open, and honest elections.

Statement 2: Since elections sometimes produce bad results, we should adopt other methods for choosing this country’s leaders.

(% who “agreed” or “agreed very strongly” with Statement 1)

Importantly, even after failed democratic leadership, Malians remain committed to elections as the best way to choose their leaders (75 percent) as well as to the rule of law (80 percent) and presidential accountability to the National Assembly (77 percent).

What do these responses tell us? Outside observers have reason to be concerned that many Malians appear to prefer a coup to the prospect of waiting out the remaining three years of Keïta’s term. Yet, while Malians are eager to see a functioning government and thriving economy, it is equally clear that they reject military rule and see democracy as their country’s path forward.

For a more detailed analysis, please see Afrobarometer Dispatch No. 386, “Malians, though eager for change from failing state and economy, still demand democracy”.

Massa Coulibaly is executive director of the Groupe de Recherche en Economie Appliquée et Théorique (GREAT) in Mali.

Carolyn Logan is director of analysis for Afrobarometer (@afrobarometer) and associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University. Find her on Twitter @carolynjlogan.

E. Gyimah-Boadi is interim CEO of Afrobarometer. Find him on Twitter @gyimahboadi.