Originally posted on the Center for International Media Assistance (CIMA) website.

Jeff Conroy-Krutz is an associate professor of political science at Michigan State University and is the editor of the Afrobarometer Working Papers Series.

Jeff Conroy-Krutz is an associate professor of political science at Michigan State University and is the editor of the Afrobarometer Working Papers Series.

Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny is Afrobarometer regional communications coordinator for anglophone West Africa, based at the Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) in Accra.

Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny is Afrobarometer regional communications coordinator for anglophone West Africa, based at the Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) in Accra.

Media liberalization and the emergence of independent media outlets in many African countries over the past few decades has played a central role in democratization. Take, for example, the case of Senegal. Just thirty years ago, there was just one, government-controlled television station. Radio was similarly restricted. This all changed in 1992 when new laws allowed for independent broadcasters. Sud FM became Senegal’s first private radio station in July 1994; Dunya FM and Nostalgie FM soon followed.

The flourishing of independent media had a direct impact on the country’s political environment. By 2000, when President Abdou Diouf ran for a fourth term, the media provided coverage to all candidates—including the opposition—and on election day conducted parallel vote tallies, which curtailed fraud in the tallying of votes. Ultimately, Diouf lost the election and peacefully handed over power to his opponent.

By 2017, there were 276 radio stations in Senegal, alongside myriad television, print, and online options. Today, the country’s independent media continue to perform important public interest functions, from exposing corruption to tackling taboo, but important subjects like sexual abuse and domestic violence.

Yet, according to new public survey data collected by Afrobarometer, an independent African research network, support for media freedom is declining among Senegalese. More worrying is the fact that this is a broader trend on the continent. Just as democracy appears to have gained ground in many parts of Africa, citizen support for media freedom has declined sharply in more than a dozen countries.

What do African citizens think of media freedom today?

While experts see media freedom as essential to a country’s development, it is not clear that citizens in many countries feel the same. In an Afrobarometer survey in which 1,200 Senegalese were asked whether they support media’s “right to publish any views and ideas without government control,” versus the government’s “right to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society,” fewer than one in five—just 18 percent—supported media freedom. A strong majority—79 percent—voiced support for government controls.

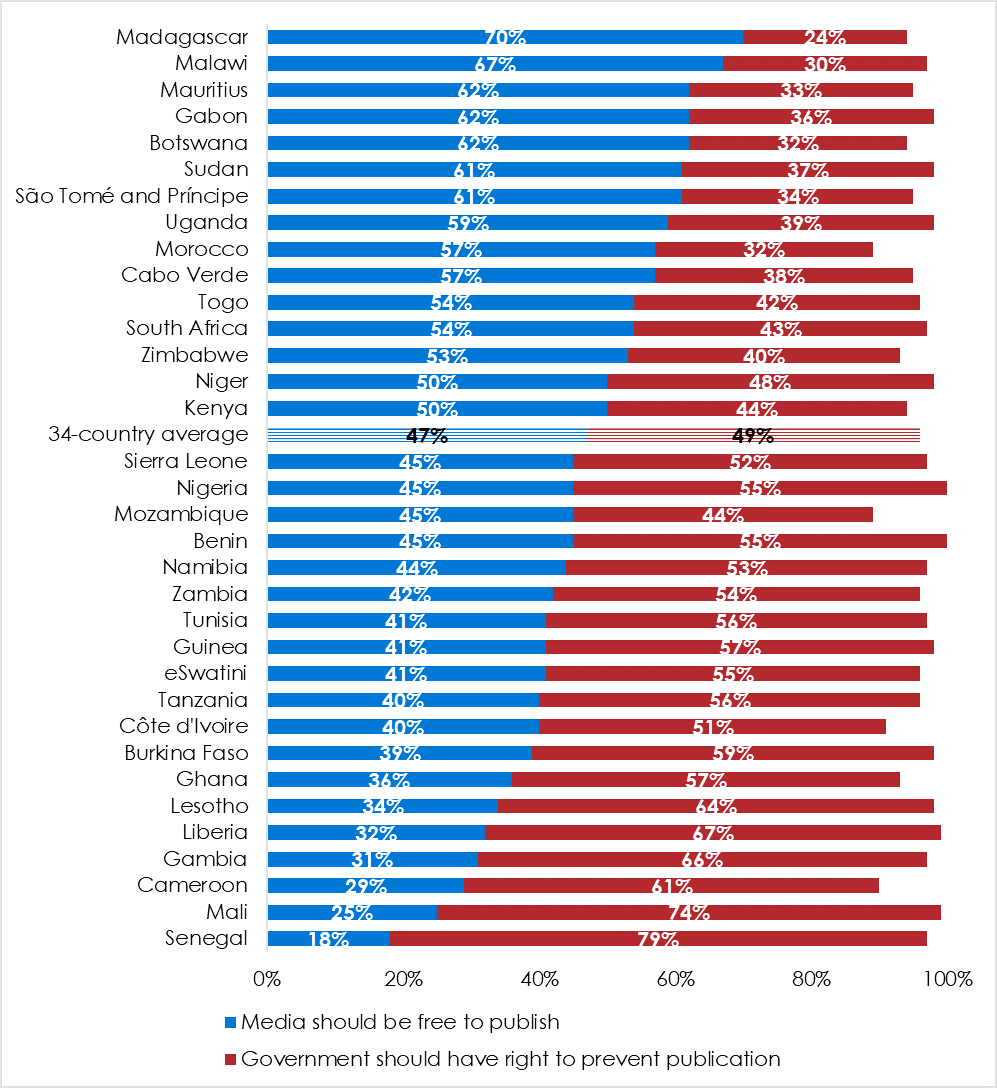

In fact, Senegal registered lower support for media freedom than any other country in Afrobarometer’s 2016-18 round of surveys. Across 34 countries, an average of 47 percent of respondents supported media freedom.

Figure 1: Support for media freedom | 34 countries | 2016/2018

Respondents were asked: Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: The media should have the right to publish any views and ideas without government control.

Statement 2: The government should have the right to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society.

(% who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with each statement)

Africans’ support for media freedoms is on the decline

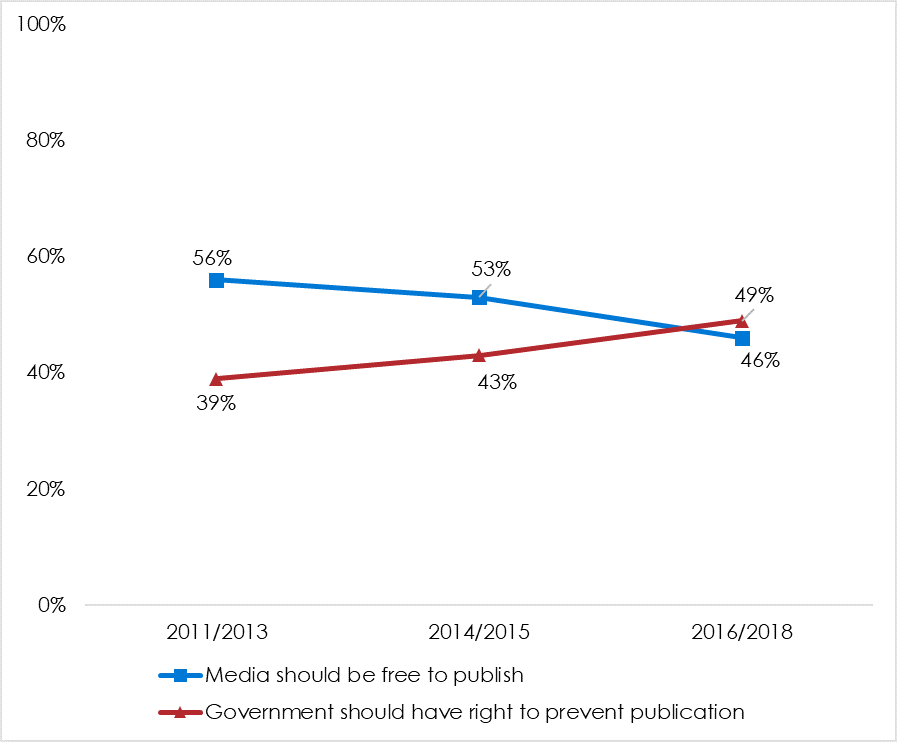

There is wide variation across countries in terms of support for media freedom, but the pattern is clear: Africans are increasingly skeptical about press freedom. In the 2011-13 Afrobarometer round of surveys, 56 percent of respondents supported media freedom, while only 39 percent favored restrictions. By the 2016-18 round, for the first time in Afrobarometer’s twenty-year history, support for restrictions on the news media exceeded support for press freedoms—49 percent to 46 percent (Figure 2). (These figures reflect only those 31 countries surveyed in both the 2011-13 and 2016-18 rounds.)

The decline is nearly universal. Twenty-five of the 31 countries surveyed in both rounds saw significant drops in support for media freedom. Declines ranged from relatively small (5 percentage points in Zimbabwe and 6 in Benin, Guinea, and Lesotho) to precipitous (21 percentage points in Tunisia and Uganda, and 33 in Tanzania).

Figure 2: Support for media freedom | 31 countries | 2011-2018

Respondents were asked: Which of the following statements is closest to your view?

Statement 1: The media should have the right to publish any views and ideas without government control.

Statement 2: The government should have the right to prevent the media from publishing things that it considers harmful to society.

(% who “agree” or “agree very strongly” with each statement)

Opposing media freedoms while supporting democracy?

Given that a free press is essential to a thriving democracy, many are concerned about crackdowns on the media that are occurring with increasing frequency in Tanzania, Uganda, and elsewhere. However, it is not clear that citizens see restrictions on the press as incompatible with democracy.

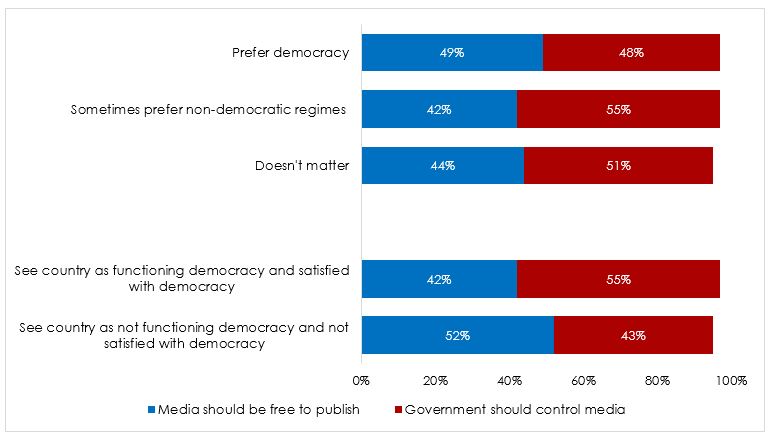

In the latest Afrobarometer surveys, those who said that “democracy is preferable to any other kind of government” (68 percent of those surveyed) were split in their attitudes about the media. Forty-nine percent supported media freedom while 48 percent supported government controls. Those who agreed that “in some circumstances, a non-democratic government can be preferable” (13 percent of those surveyed) leaned more strongly in favor of government controls, 55 percent to 42 percent (Figure 3). There is also a significant population who see their country as a functioning democracy and are satisfied with the way democracy is working, yet who also support media limits. In fact, these individuals are more likely to support government controls (55 percent) than those who perceive their countries to be non-democratic and are dissatisfied with the way democracy works (43 percent).

Figure 3: Attitudes toward democracy vs. support for media freedom | 34 countries | 2016/2018

In Senegal, 79 percent of those who preferred democracy supported government controls, versus just 18 percent who favored absolute media freedom. What might explain this paradox?

One possibility is that many Africans’ attitudes on the media are shifting in response to increasing attacks on the press by political leaders. In fact, those with more-positive assessments of the incumbent government are significantly more supportive of restrictions on media. Fifty-five percent of those who said that they trust their country’s current leader “somewhat” or “a lot” (52 percent of all surveyed) supported media restrictions, versus just 43 percent of those who trust their leader “just a little” or “not at all” (44 percent of all surveyed).

However, it bears noting that over four in ten of those who said they do not trust their current leader were still willing to allow governments to restrict media freedom. This suggests a deep and widespread potential dissatisfaction with current media environments.

What might Africans not like about their current media? Many outlets are affiliated with specific parties and politicians, and are consequently biased. Others spread so-called “fake news,” or even propagate hate speech and incendiary language. Social media magnify these elements.

In fact, there is additional evidence in the survey that Africans think media freedom has gone too far. Africans are more likely to see media freedom as increasing in their country (43 percent) than as declining (32 percent), but many apparently do not view this positively. Fifty-four percent of those who think media freedom is increasing supported the ability of governments to impose restrictions, while only 43 percent who favored media freedom. And many countries that have seen the sharpest declines in support for media freedoms, such as Sierra Leone, Ghana, Tunisia, and Cabo Verde, are among the continent’s democratic standouts.

To many of these citizens, the negatives associated with broader media freedoms might be seen as threatening to economic development and social stability. They might even bring violence, and too much freedom might seem threatening to democracy itself. In this light, empowering some authority to limit media freedoms is potentially the lesser of two evils.

Does living under authoritarianism lead to recognition of the importance of free media?

The only country where support for media freedom increased was Sudan, where support increased from 49 percent in 2013 to 61 percent in 2018. Sudan has consistently been rated as having one of the most-restrictive media environments in the world, and most broadcasters have been state-run or carefully avoid criticizing the government. In 2019, as protests that brought down President Omar al-Bashir ramped up, violations of press freedoms escalated, with arrests of journalists, accreditation withdrawals, and confiscations of publications. As the struggle over Sudan’s future continues, a near-total internet shutdown has hampered pro-democracy activists.

In such a context, it is easy to see why supporters of democracy would also support press freedom. Among Sudanese preferring democracy (61 percent of those surveyed), nearly two-thirds (64 percent) support press freedoms, versus only 35 percent who support government’s ability to restrict media. Sudanese who see value in authoritarianism (17 percent) are more supportive of controls (44 percent), yet even in this group, a majority supports press freedom (54 percent).

Generally, among Africans who see press freedoms as on the decline—a common assessment in some of Africa’s less-competitive political systems, such as Uganda (44 percent), Tanzania (45 percent), eSwatini (46 percent), Sudan (47 percent), and Gabon (66 percent)—support for unfettered media is broader than support for government restrictions, 54 percent to 44 percent.

Media as a threat or a democratic necessity?

The striking contrast between Senegal and Sudan is informative. The former has one of the continent’s most-vibrant media environments, and its generally democracy-supporting citizens seem to think it should be reined in. On the other hand, Sudanese are all too familiar with the costs that government control of the media can bring, and this shows in their increasing support for media freedoms.

To be sure, many who express skepticism of media freedom likely do not support total state control of the media. However, seemingly small increases in restrictions can develop into more-serious attacks on freedom of expression in the long run. Government restrictions on the press are generally incompatible with democracy, but fewer and fewer citizens seem to recognize this.

International and domestic actors interested in promoting and maintaining democracy in these countries should take a two-pronged approach. First, civic education efforts must redouble their attention to the central importance of media freedom in democratic regimes. This might involve concrete examples of how free and independent media support open electoral competition, give voices to citizens, expose corruption, and enhance government accountability. However, the negatives associated with media development in Africa, including “fake news” and hate speech, cannot be swept under the rug, as governments will continue to take advantage of their populations’ growing skepticism about the benefits of an unfettered media. Therefore, media development efforts must continue to focus on enhancing professionalism and helping media practitioners develop their own robust, self-regulating mechanisms. When governments step into such matters, as African citizens seem to be increasingly calling for, the outcome often leads to broader chilling effects on democracy.