The second in Afrobarometer’s special democracy summit series on Africa.

Originally published on the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, where our regular Afrobarometer series explores Africans’ views on democracy, governance, quality of life, and other critical topics.

Over the past two decades, China and Africa have dramatically expanded their political and economic ties. China’s leading role in development financing has some observers concerned about political influence as well as economic power and debt.

Washington-based think tank Freedom House gives China a score of 9 out of 100 on its Global Freedom Index, compared to 83, 90 and 93, respectively, for the United States and former colonial powers France and the United Kingdom. Unlike Western donors, China doesn’t condition its assistance on political agendas such as the promotion of democracy and human rights.

Democracy advocates worry that Africa’s fledgling democratic governments’ ability to turn to China’s condition-free resources may make it harder to promote democratic and accountable governance across the continent.

Last week, in the first of a series leading up to December’s Summit for Democracy, we learned that Africans want more democracy than they feel they’re getting. This week we examine whether China’s power on the African continent is associated with weaker democratic commitment or inflates Africans’ assessments of how much democracy their governments are providing.

Afrobarometer just completed its eighth round of surveys (2019-2021), consisting of 48,084 face-to-face interviews across 34 countries. Here’s what we’ve learned.

Attitudes toward China don’t affect demand for democracy

In exploring China’s influence, Afrobarometer begins by asking respondents which country offers “the best model for the future development of [your] country.” One in three respondents (33%) rank the United States as their favored model, while 22% prefer to emulate China. Others choose South Africa (12%), their country’s former colonial power (11%), or their own country’s model (7%).

When we look only at respondents who say they prefer democracy over all other political systems, 35% favor the U.S. model for their country’s development, and 23% choose China’s.

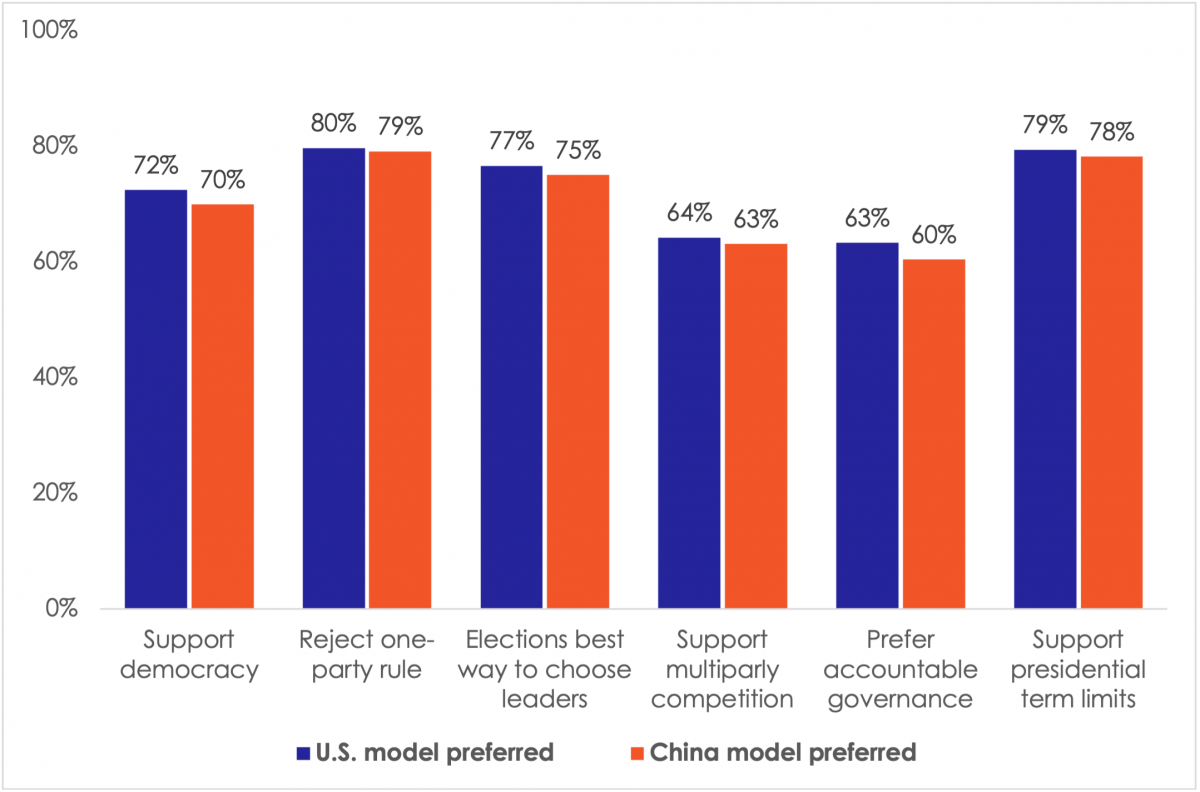

Africans who prefer China as a development model aren’t necessarily thinking about governance; they’re about as likely as those who favor the U.S. model to express support for democracy, elections, multiparty competition, and accountable government, and as likely to reject authoritarian alternatives such as a one-party state or military rule, as you can see in the figure below.

Figure 1: Support for democratic norms and institutions, by preference for China or U.S. model | 34 countries | 2019/2021

Afrobarometer also asks respondents how much influence China’s economic activities have on their own country’s economy; 61% say “some” or “a lot,” down 12 percentage points since 2014/2015. Asked whether China’s influence is mostly positive or mostly negative, 63% say it is “somewhat” or “very positive,” while 60% say the same about the U.S. Here again, respondents who rate China’s influence as “very positive” are just as likely as those who see U.S. influence as “very positive” to support democratic norms and institutions.

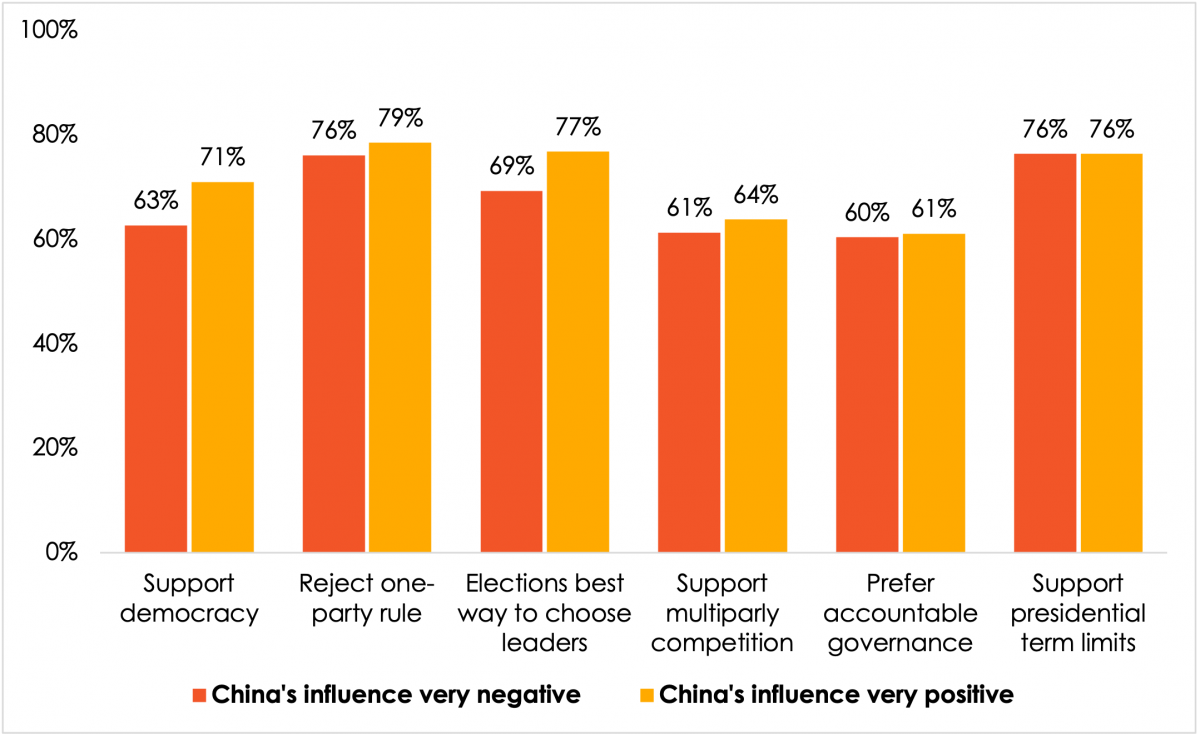

We compared support for democracy among those who rate China’s influence as “very negative” and those who rate it as “very positive.” Contrary to the fears of some democracy advocates, those who see China’s influence as positive are more likely to say they prefer democracy (71% vs. 63% of those who see China’s influence as negative) and to support elections (77% vs. 69%). Otherwise, differences are minor.

Figure 2: Support for democratic norms and institutions, by perceptions of China’s influence | 34 countries | 2019/2021

In brief, positive attitudes toward China do not appear to undermine Africans’ commitment to democracy.

A “China effect” on assessments of democratic supply?

When it comes to how much democracy Africans are getting, we do see modest evidence of a “China effect”: When citizens admire China as a development model, they feel better about their own country’s democratic governance.

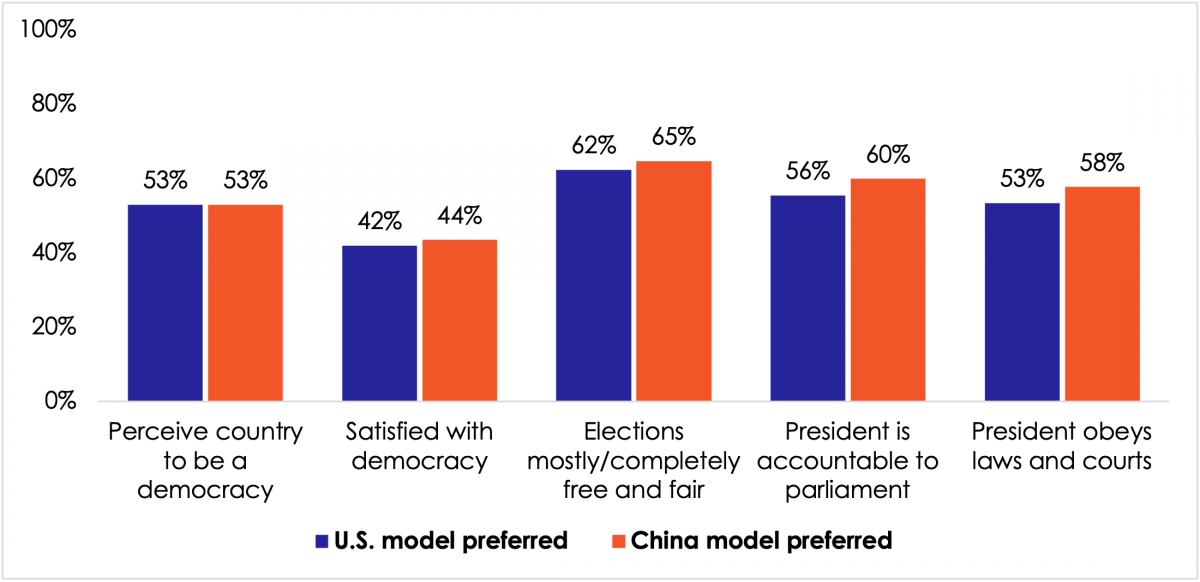

In evaluating the extent of democracy in their countries, respondents who prefer the China model do not differ from those who prefer the U.S. model, as you can see in the figure below. But on measures of satisfaction with democracy, the quality of elections, and accountability of presidents to parliament and to the courts, Africans who prefer the China model evaluate democratic conditions in their own country a bit more positively.

Figure 3: Assessments of supply of democracy, by preference for China or U.S. model | 34 countries | 2019/2021

This may suggest that Africans with a pro-China stance hold their governments to slightly lower democratic standards. But the differences are not large enough to suggest that China’s presence significantly changes Africans’ perceptions of their countries’ political systems.

No strings wanted

While analysts in the West worry about China’s lack of political stipulations on its loans and development assistance, Africans may see this as an attractive feature, not a bug. When Afrobarometer asks respondents whether donor countries should enforce strict requirements for how their funds are spent, 55% say no. Similarly, 51% reject conditions designed to ensure that recipient governments promote democracy and respect human rights. People want their own governments – not China, the United States or other countries – to set the nation’s economic and political standards. This may help explain why China’s economic influence does not substantially affect attitudes toward or assessments of democracy, whether positively or negatively.

China’s presence is more economic than political

In short, Chinese economic influence across Africa does not seem to be affecting citizens’ views of the democratic project.

The evidence suggests that Africans see China as an economic presence rather than a political one. Despite some Western fears, Chinese development assistance does not appear to promote autocracy and undermine democracy – at least not from the perspective of ordinary Africans.

Carolyn Logan (@carolynjlogan) is director of analysis for Afrobarometer and associate professor in the department of political science at Michigan State University.

Josephine Appiah-Nyamekye Sanny (@JAppiahNyamekye) is knowledge translation manager for Afrobarometer.

Related content