Christiaan Keulder is the owner of Survey Warehouse and national investigator for Afrobarometer in Namibia.

Originally published on the Washington Post Monkey Cage blog, where our biweekly Afrobarometer Friday series explores Africans’ views on democracy, governance, quality of life, and other critical topics.

Corruption is as old as power and as current as the morning headlines, in Africa as in the rest of the world. South Africa continues to wrestle with the fallout of “state capture” — systemic political corruption by private interests — during Jacob Zuma’s presidency. Namibians are gearing up for the high-profile #Fishrot trial involving two ministers accused of accepting bribes from an Icelandic company in exchange for lucrative fishing rights in the country’s waters. Allegations of corruption involving covid-19 pandemic relief pour in from Zimbabwe, Somalia, Kenya, Nigeria and other countries.

Analysts estimate that developing countries lose $1.26 trillion per year to corruption, theft and tax evasion — enough to lift 1.4 billion people above the poverty line for six years.

And ordinary Africans say things are getting worse. In Afrobarometer surveys in 18 African countries in late 2019 and early 2020, a majority of citizens say corruption increased in their country during the previous year and their government is doing too little to control it. Perceptions and experiences of corruption vary widely by country, but a majority of citizens in every surveyed country say they risk retaliation should they get involved by reporting corruption to the authorities.

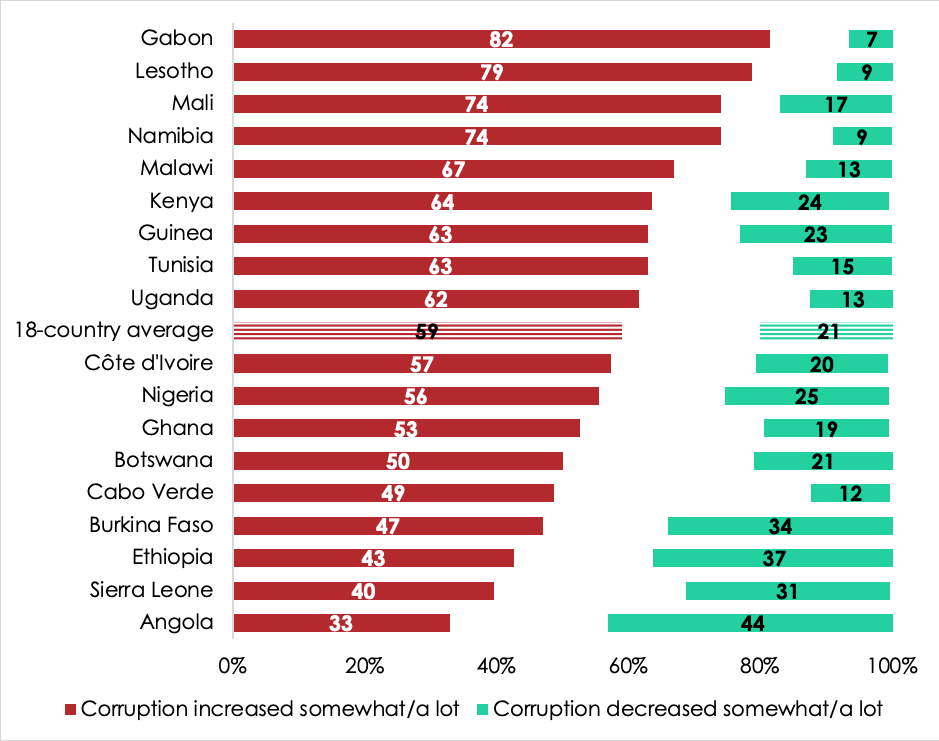

Many Africans feel corruption is on the rise

On average across 18 countries, six in 10 Africans (59%) say that corruption increased in their country during the previous year, including 41% who say it “increased a lot.” Only one in five (21%) believe it decreased at least “somewhat” (see Figure 1).

Perceptions that corruption is getting worse are most widespread in Gabon (82%), Lesotho (79%), and Mali (74%), as well as in Namibia (74%) — even though survey fieldwork in Namibia was completed before the #Fishrot corruption scheme was exposed in November 2019. Angola is the only surveyed country where more people see a decrease (44%) than an increase (33%) in corruption.

Figure 1: Corruption increased/decreased during the previous year | 18 countries | 2019/2020

Respondents were asked: In your opinion, over the past year, has the level of corruption in this country increased, decreased, or stayed the same? Source: Afrobarometer.

Respondents were asked: In your opinion, over the past year, has the level of corruption in this country increased, decreased, or stayed the same? Source: Afrobarometer.

The situation has worsened most dramatically in Mali, where the proportion reporting that corruption is increasing has risen by 43 percentage points since 2014, from 31% to 74%, followed by Gabon (+30 points), Côte d'Ivoire (+25 points) and Guinea (+25 points). In contrast, in three countries the number who report that corruption is increasing has dropped by large margins: Sierra Leone (-30 percentage points), Ghana (-23 points) and Nigeria (-20 points).

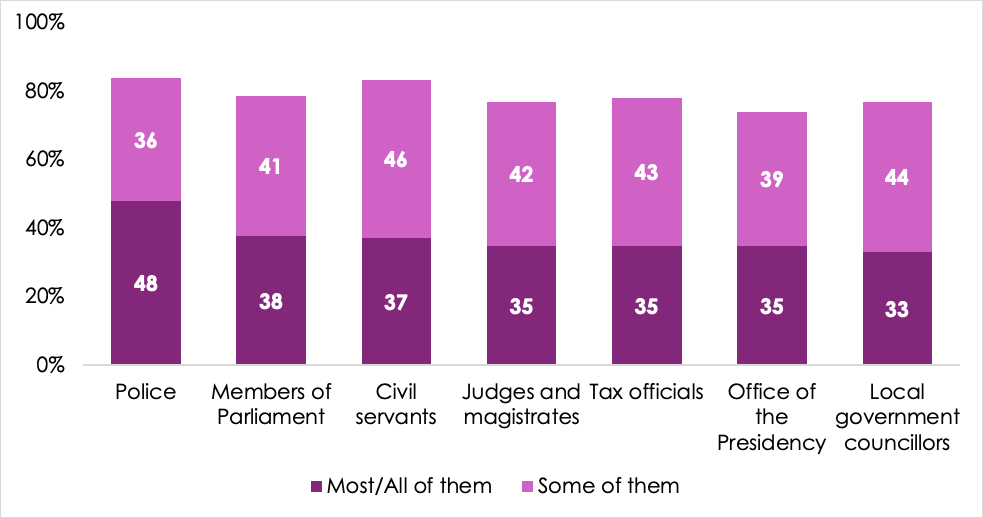

Africans see corruption in key institutions

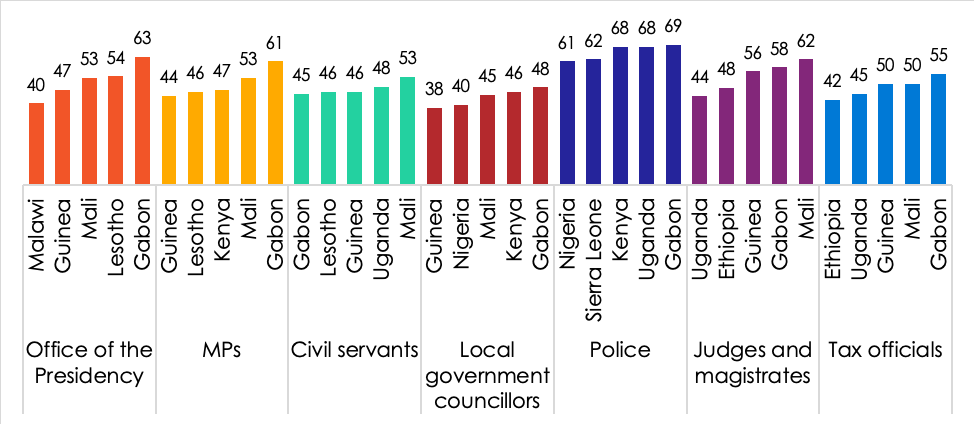

In assessing key public institutions, Africans are most likely to see the police as corrupt; almost half (48%) of Africans say “most” or “all” police officials are involved in graft, in addition to 36% who see “some of them” as corrupt. More than one-third of citizens see widespread corruption in parliament, the civil service, the legal system, the tax office and the presidency (see Figure 2).

Perceptions of institutional corruption have increased modestly over the past decade. Across 11 countries surveyed in both 2008/2009 and 2019/2020, the share of citizens who see “most” or “all” officials as corrupt increased by 11 percentage points for the presidency, by 9 points for members of parliament, and by 7 points for judges/magistrates while remaining steady for the police, civil servants and local government councillors.

Figure 2: Corruption in key public institutions | 18 countries* | 2019/2020

Respondents were asked: How many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? (% who say “most” or “all”)

Respondents were asked: How many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? (% who say “most” or “all”)

*The question about local government councillors was not asked in Angola. Source: Afrobarometer.

Perceived corruption varies greatly across countries and institutions, but three countries — Guinea, Gabon and Mali — appear consistently among the five worst performers with regard to all seven institutions (see Figure 3). Cabo Verde consistently ranks at the least corrupt end of the scale across all institutions, frequently joined by Botswana and Tunisia.

Figure 3: Countries with highest perceived corruption | by key institution | 18 countries | 2019/2020

Respondents were asked: How many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? (Figure shows, for each of seven institutions, the five countries where the largest proportions of respondents say “most” or “all” officials are corrupt.) Source: Afrobarometer.

Respondents were asked: How many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? (Figure shows, for each of seven institutions, the five countries where the largest proportions of respondents say “most” or “all” officials are corrupt.) Source: Afrobarometer.

Bribes are a path to public services

While large-scale graft makes headlines, ordinary Africans encounter corruption most often in the form of petty bribery as a way — sometimes the only way — to access much-needed services.

Fully one-third of Africans who dealt with the police during the previous year say they had to pay a bribe (35% of those who sought police assistance; 33% of those who encountered the police in other situations, such as a traffic stop or investigation) — experiences in line with the perception of the police as the most corrupt public institution.

But many citizens also report paying bribes to obtain a government document (25%), medical care (20%) or assistance at a public school (19%).

In Cabo Verde, only 4% of citizens report having to pay a bribe during the past year to obtain any of these services. Namibia (7%) and Botswana (9%) also perform relatively well. But in Uganda (53%), Guinea (47%), Sierra Leone (46%) and Kenya (45%), around half the population was exposed to bribery in exchange for these key public services during the previous 12 months.

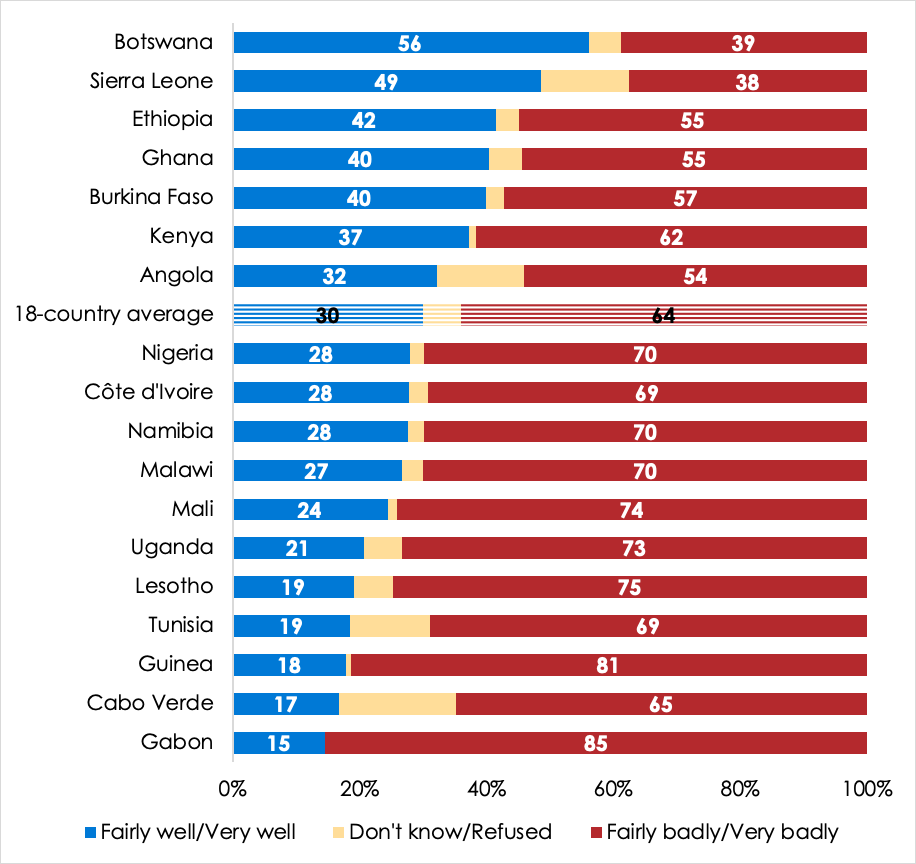

Governments fail in the fight against corruption

If citizens expect their government to lead the fight against corruption, most are disappointed: Almost two-thirds (64%) say their government is doing a poor job on this front. Botswana is the only surveyed country where a majority (56%) praise their government’s anti-corruption efforts (see Figure 4).

In 12 of the 18 countries, fewer than one in three citizens give their government passing marks on corruption, including fewer than one in five Gabonese, Cabo Verdeans, Guineans, Tunisians and Basotho.

Figure 4: Government performance in fighting corruption | 18 countries | 2019/2020

Respondents were asked: How well or badly would you say the current government Is handling the following matters, or haven’t you heard enough to say: Fighting corruption in government? Source: Afrobarometer.

Respondents were asked: How well or badly would you say the current government Is handling the following matters, or haven’t you heard enough to say: Fighting corruption in government? Source: Afrobarometer.

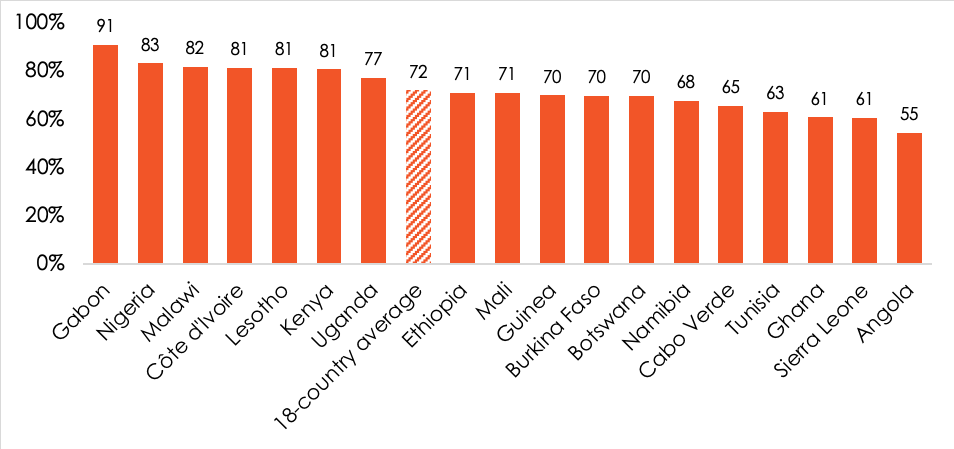

Fear of retaliation

Ordinary citizens who want to get involved in fighting corruption face a significant hurdle: Almost three-fourths (72%) of Africans say people risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they report corruption to the authorities. Only 24% believe they can speak up without fear (see Figure 5).

Even in Angola, the country with the lowest perceived risk of retaliation, a majority (55%) fear negative consequences if they report corruption. In Gabon, fear of retaliation is nearly universal (91%).

Figure 5: Risk retaliation for reporting corruption | 18 countries | 2019/2020

Respondents were asked: In this country, can ordinary people report incidences of corruption without fear, or do they risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they speak out? (% who say they risk retaliation). Source: Afrobarometer.

Respondents were asked: In this country, can ordinary people report incidences of corruption without fear, or do they risk retaliation or other negative consequences if they speak out? (% who say they risk retaliation). Source: Afrobarometer.

Combined with perceptions of increasing corruption and inadequate government response, public expectations of being punished for speaking up do not bode well for an effective anti-corruption fight.

For advocates of African development, this is not good news, because unless corruption is controlled, achieving all the other Sustainable Development Goals will be very hard indeed.

Related content