Originally posted on the Monkey Cage blog.

Edem E. Selormey is the Afrobarometer field operations manager for North, East and Anglophone West Africa, based at the Ghana Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana).

Carolyn Logan is deputy director of Afrobarometer and associate professor in the Department of Political Science at Michigan State University.

The 2019 U.N. Climate Action Summit brings thousands of government officials, climate and energy experts, and private-sector and civil-society representatives to New York.

Months earlier, more than 3,000 African government, business and civil-society leaders gathered for Africa Climate Week 2019 to lay plans for strengthening cross-sector engagement for climate action. Participants emphasized the need to align climate plans with development plans and to ensure adequate national and international funding to implement national climate action plans.

Most African countries have signed on to international climate agreements, including the 2016 Paris climate accord, which spells out a commitment from developed countries to allocate $100 billion by 2020 for climate adaptation and the mitigation needs of developing countries.

Although the continent’s contribution to global greenhouse emissions is small (about 4 percent of the world’s total in 2017), African nations are among the countries most vulnerable to and least prepared for climate change. Even with external support, building climate resilience in Africa will take significant political will and resources, as well as support from populations that understand the need to prioritize climate action.

The largest survey exploring Africans’ views on climate change, conducted in 34 countries between late 2016 and late 2018, found limited popular knowledge alongside widespread perceptions that climate change is “making life worse.” Here is what this Afrobarometer survey revealed.

Climate conditions threaten agriculture

Before any mention of “climate change,” Afrobarometer asked 45,823 respondents about their own observations of changes in weather patterns. In 30 of the 34 countries, pluralities reported that climate conditions for agricultural production had worsened over the past decade — an assessment that was particularly common in Uganda (85 percent), Malawi (81 percent) and Lesotho (79 percent).

East Africans (63 percent) were almost twice as likely as North Africans (35 percent) to report that weather for growing crops had worsened. And people engaged in occupations related to agriculture (farming, fishing or forestry) were more likely to report negative weather effects (59 percent) than those with other livelihoods (45 percent).

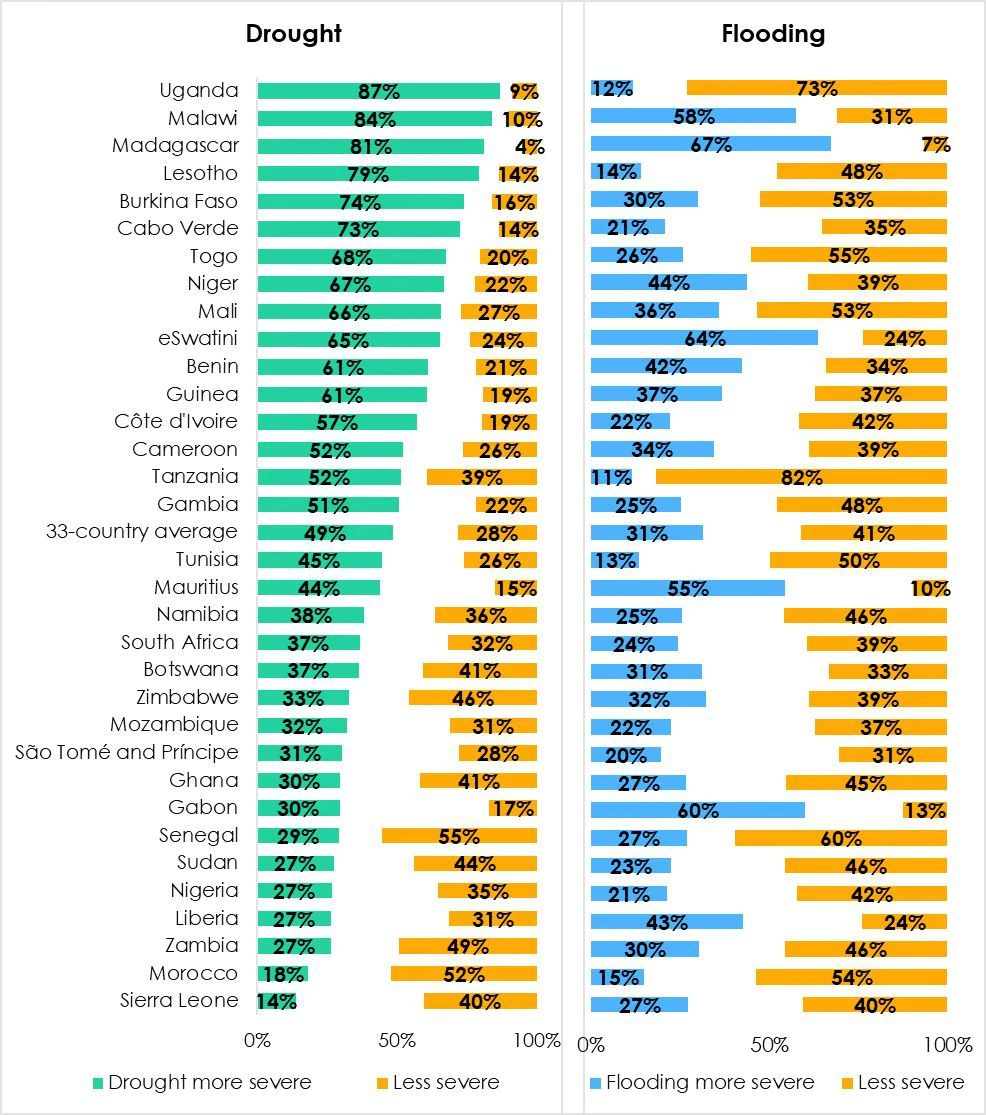

These results suggest that many Africans see changes in weather patterns that directly affect farmers and herders. In most cases, respondents identified worsening drought conditions, as shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1: Changing severity of droughts and flooding in Africa. Afrobarometer asked respondents whether drought and flooding in their region had become more or less severe over the past 10 years. This question was not included in the Kenya survey.

How widespread is awareness of climate change?

In some of the most severely affected countries, including Uganda, Malawi and Cabo Verde, substantial majorities of the population were familiar with the term “climate change.” Overall, nearly 6 in 10 Africans had at least heard of the term.

In other countries, awareness of climate change was much less widespread. These include some of the continent’s largest populations, such as Nigeria, where only 50 percent of respondents said they knew about climate change, and South Africa (41 percent).

Groups less familiar with the concept of climate change included rural residents, women, the poor, the less-educated, people who work in agriculture and those with limited exposure to the news media.

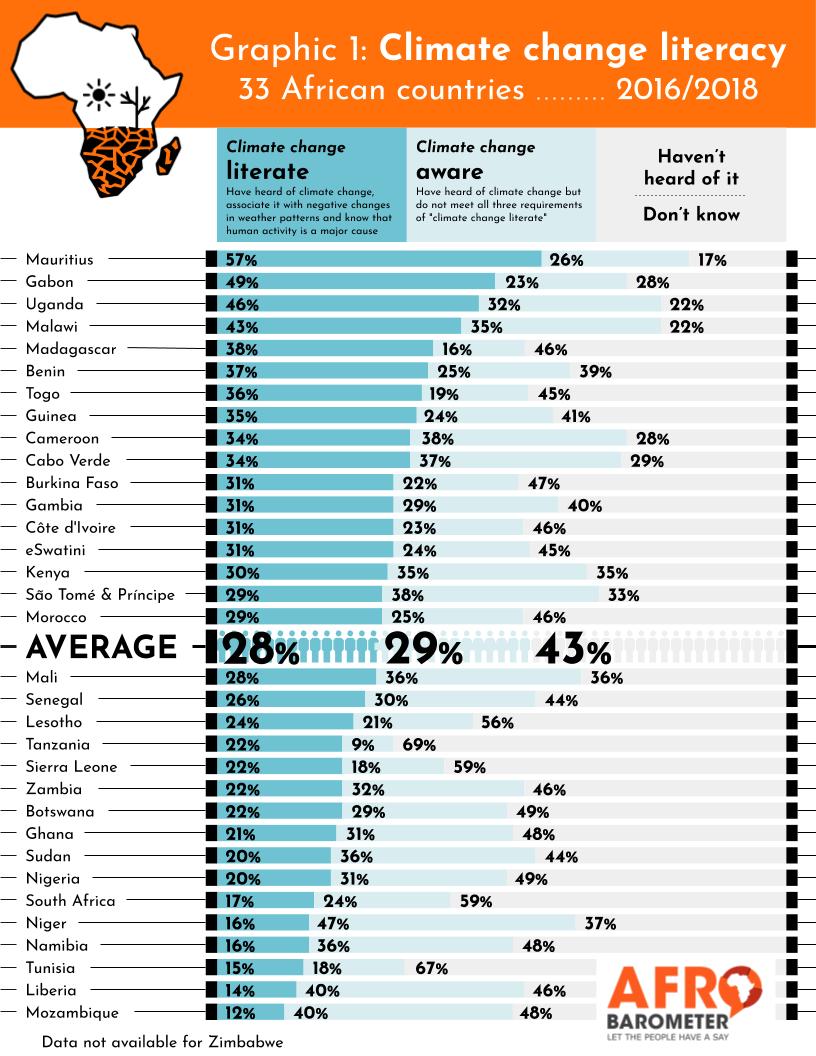

But the survey revealed a deeper information issue. Only about 28 percent overall were “climate change literate” in the sense that they also associate climate change with negative changes in weather patterns and recognize that human activity plays a part in these effects, as shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2: “Climate change literacy” in Africa Percentage of respondents who are “climate change literate,” meaning they not only have heard of climate change but also associate it with negative changes in weather patterns and recognize that human activity plays a part in causing it. The survey in Zimbabwe did not include all relevant questions.

We don’t know how that compares to, say, populations in Asia or the Americas. But in one of the global regions most susceptible to the potential harms of climate change, analysts will probably see boosting climate change literacy as key to motivating governments to step up their response to this global challenge.

Climate change makes ‘life worse’

Overall, two-thirds (67 percent) of Africans who had heard of climate change said it was making their lives worse. The negative effect was felt especially strongly in East Africa, where 9 out of 10 citizens who had heard of climate change (89 percent) said it was making life worse. Only about half as many North Africans (46 percent) saw a negative impact on the quality of life.

Are there ways to stop climate change?

Nearly three-fourths (71 percent) of those who were aware of climate change agreed that it needs to be stopped, but only 51 percent expressed confidence about their ability to make a difference.

What do these results tell us about climate resilience in Africa? Many citizens are seeing harmful changes in weather patterns, but fewer than 3 in 10 have a basic understanding of climate change. Given the continent’s low greenhouse gas emissions and high vulnerability to climate change, consensus-building initiatives for prevention, early-warning, adaptation and mitigation measures may be among the important contributions that African nations can take to the U.N. Climate Action Summit in New York.